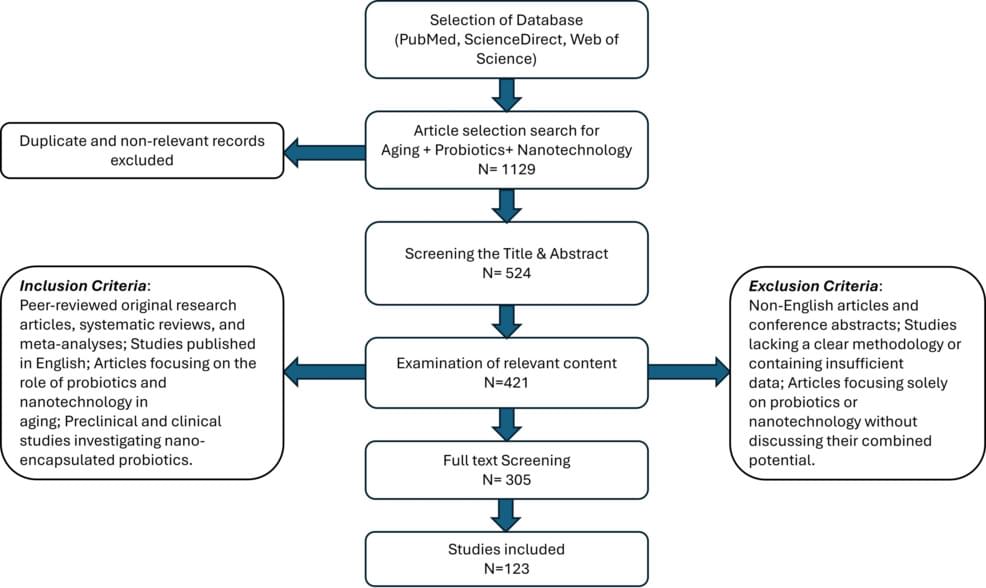

The geriatric population, comprising ages 65 and above, encounters distinct health obstacles because of physiological changes and heightened vulnerability to diseases. New technologies are being investigated to tackle the intricate health requirements of this population. Recent advancements in probiotics and nanotechnology offer promising strategies to enhance geriatric health by improving nutrient absorption, modulating gut microbiota, and delivering targeted therapeutic agents. Probiotics play a crucial role in maintaining gut homeostasis, reducing inflammation, and supporting metabolic functions. However, challenges such as limited viability and efficacy in harsh gastrointestinal conditions hinder their therapeutic potential. Advanced nanotechnology can overcome these constraints by enhancing the efficacy of probiotics through nano-encapsulation, controlled delivery, and improvement of bioavailability. This review explores the synergistic potential of probiotics and advanced nanotechnology in addressing age-related health concerns. It highlights key developments in probiotic formulations, nano-based delivery systems, and their combined impact on gut health, immunity, and neuroprotection. The convergence of probiotics and nanotechnology represents a novel and transformative approach to promoting healthy aging, paving the way for innovative therapeutic interventions.