A test using blood and saliva samples could help track aging and guide targeted interventions to maintain mental and physical function as people advance in age.

Alternative models for studying aging have employed unicellular organisms such as the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Studying replicative aging in yeast has revealed insights into evolutionarily conserved enzymes and pathways regulating aging[ 12-14 ] as well as potential interventions for mitigating its effects.[ 15 ] However, traditional yeast lifespan analysis on agar plates and manual separation cannot track molecular markers and yeast biology differs from humans.[ 16 ]

Animal models, including nematodes, flies, and rodents, play a vital role in aging research due to their shorter lifespans and genetic manipulability, making them useful for mimicking human aging phenotypes.[ 17 ] These models have provided many insights into the fundamental understanding of aging mechanism. However, animal models come with several limitations when applied to human aging and age-related diseases. Key issues include limited generalizability due to species-specific differences in disease manifestation and physiological traits. For example, animal models often exhibit physiological differences, age at different rates, and may not fully replicate human conditions like cardiovascular disease,[ 18 ] immune response,[ 19 ] neurodegenerative diseases,[ 20 ] and drug metabolism.[ 21 ] Furthermore, in vivo models, such as rodents and non-human primates, suffer from limitations such as high costs, low throughput, ethical concerns, and physiological differences compared to humans. The use of shorter lifespan or accelerated aging models, along with the absence of long-term longitudinal data, can further distort the natural aging process and hinder our understanding of aging in humans. Additionally, many animal models rely on inbred strains, which lack genetic diversity and may not fully represent evolutionary complexity.[ 22 ]

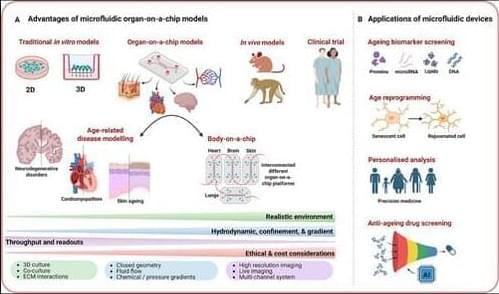

In recent years, microfluidics has emerged as a promising tool for studying aging, offering of physiologically relevant 3D environments with high-throughput capabilities that surpass the limitations of traditional 2D cultures and bridge the gap between animal models and human As a multidisciplinary technology, microfluidics processes or manipulates small volumes of fluids (from pico to microliters) within channels measuring 10–1000 µm.[ 23 ] Traditional fabrication methods, such as photolithography and soft lithography, particularly using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), remain widely used due to their cost-effectiveness and biocompatibility. However, newer approaches, including 3D printing, injection molding, and laser micromachining, offer greater flexibility for rapid prototyping and the creation of complex architectures. Design considerations are equally critical and are tailored to the specific application, focusing on parameters such as channel geometry, fluid dynamics, material properties, and the integration of on-chip components like valves, sensors, and actuators. A comprehensive overview of the design and fabrication of microphysiological systems is beyond the scope of this review; readers are referred to existing reviews for further detail.[ 24-26 ] Microfluidic devices offer numerous advantages, including reduced resource consumption and costs, shorter culture times, and improved simulation of pathophysiological conditions in 3D cellular systems compared to other model systems (Figure 1).[ 27 ] Therefore, microfluidics platforms have been extensively employed in various domains of life science research, such as developmental biology, disease modeling, drug discovery, and clinical applications,[ 28 ] positioning this technology as a significant avenue in the field of aging research.

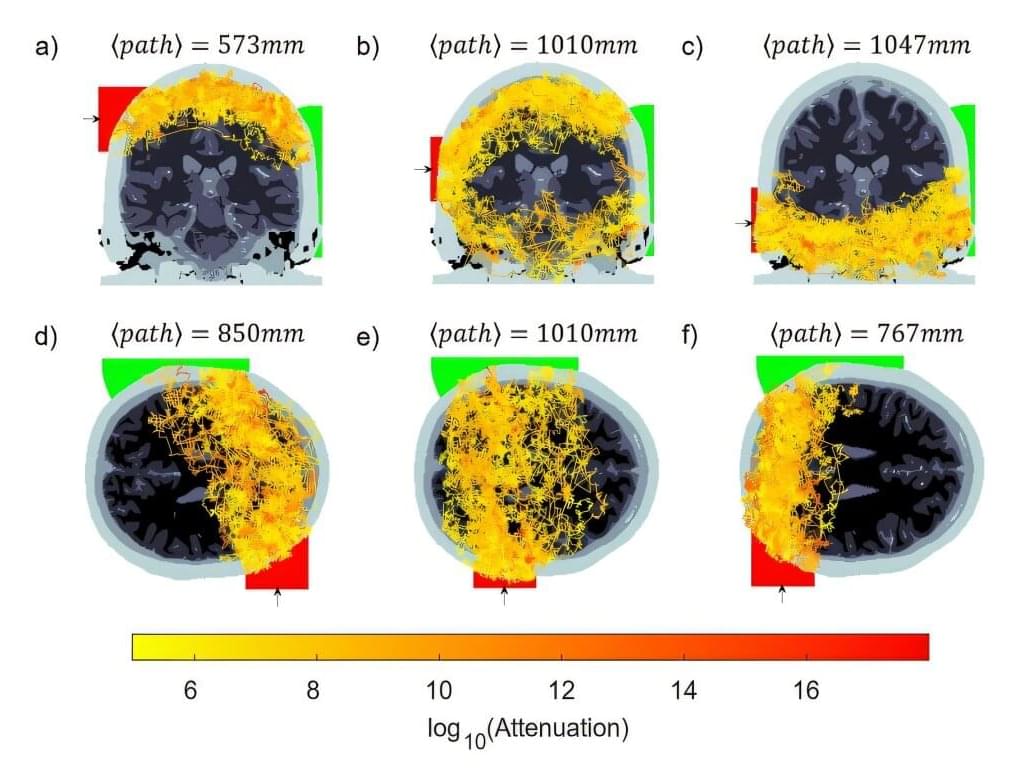

For decades, scientists have used near-infrared light to study the brain in a noninvasive way. This optical technique, known as fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy), measures how light is absorbed by blood in the brain, to infer activity.

Valued for portability and low cost, fNIRS has a major drawback: it can’t see very deep into the brain. Light typically only reaches the outermost layers of the brain, about 4 centimeters deep—enough to study the surface of the brain, but not deeper regions involved in critical functions like memory, emotion, and movement.

This drawback has restricted the ability to study deeper brain regions without expensive and bulky equipment like MRI machines.

A team of scientists at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center (The Institute) has made a landmark discovery that sheds light on how the immune system protects the gut during infection. By studying intestinal worms—also known as helminths—the team, led by Professor Irah King, uncovered a previously unknown immune mechanism that preserves intestinal function in the presence of persistent infection.

Their finding, published in the journal Cell, could pave the way for new treatments for helminth infections, which affect over two billion people worldwide at some point in their lives, as well as for other intestinal diseases.

The results could also help revisit older therapeutic strategies that were previously dismissed due to an incomplete understanding of biological processes.

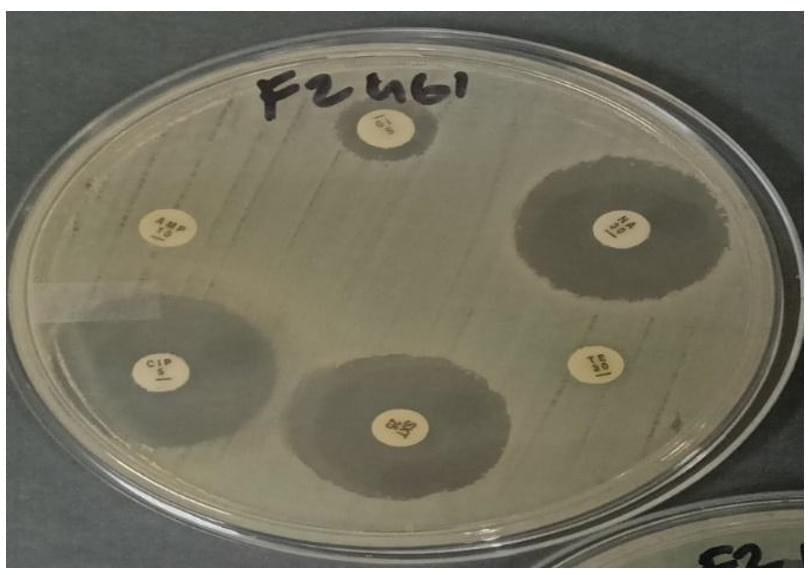

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a common bacterium that lives in the intestines of animals and humans, and it is often used to identify fecal contamination within the environment. E. coli can also easily develop resistance to antibiotics, making it an ideal organism for testing antimicrobial resistance—especially in certain agricultural environments where fecal material is used as manure or wastewater is reused.

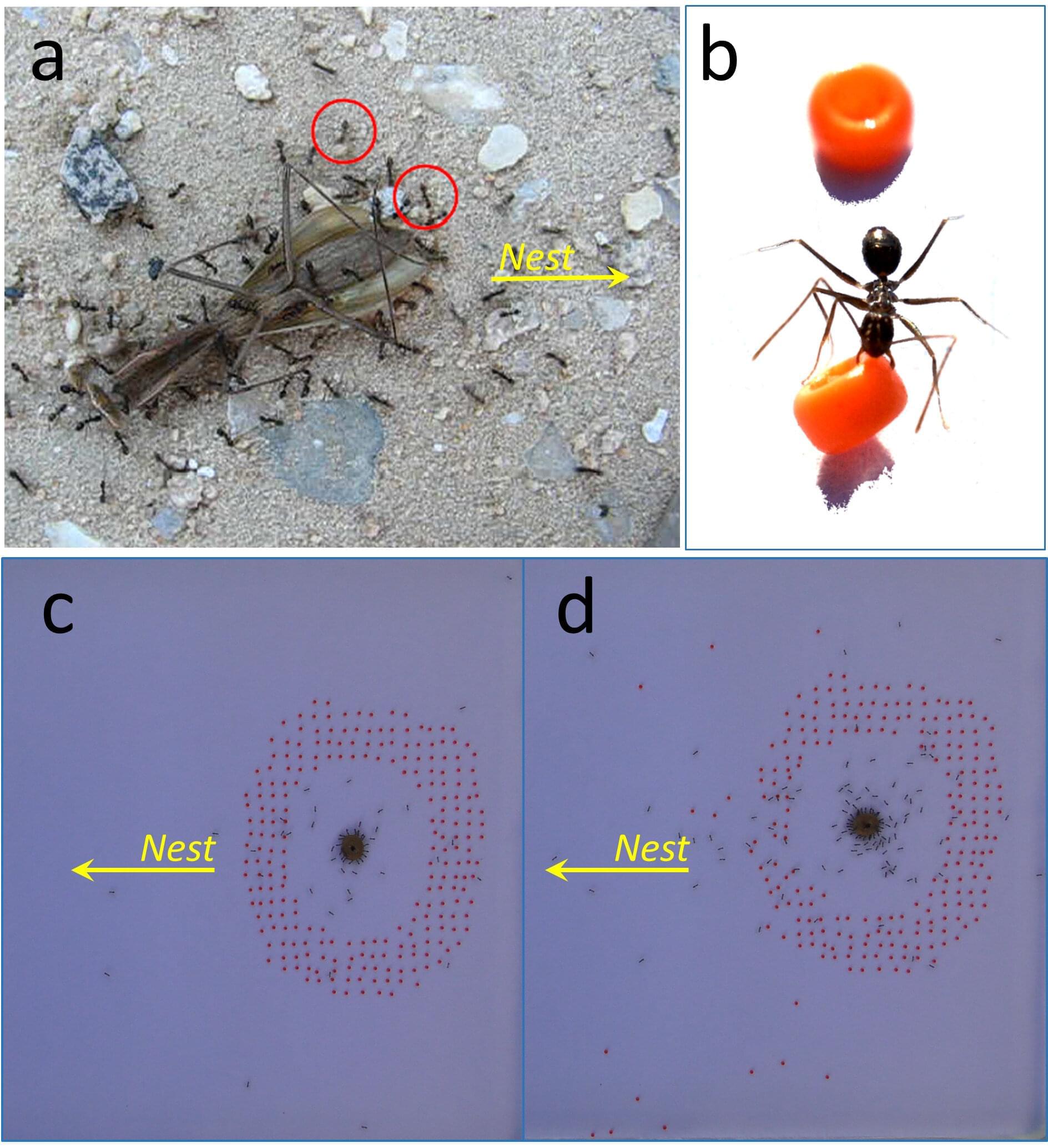

Among the tens of thousands of ant species, incredible “intelligent” behaviors like crop culture, animal husbandry, surgery, “piracy,” social distancing, and complex architecture have evolved.

Yet at first sight, the brain of an ant seems hardly capable of such feats: it is about the size of a poppy seed, with only 0.25m to 1m neurons, compared to 86bn for humans.

Now, researchers from Israel and Switzerland have shown how “swarm intelligence” resembling advance planning can nevertheless emerge from the concerted operation of many of these tiny brains. The results are published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

There are more than 100,000 people on organ transplant lists in the U.S., some of whom will wait years to receive one—and some may not survive the wait. Even with a good match, there is a chance that a person’s body will reject the organ. To shorten waiting periods and reduce the possibility of rejection, researchers in regenerative medicine are developing methods to use a patient’s own cells to fabricate personalized hearts, kidneys, livers, and other organs on demand.

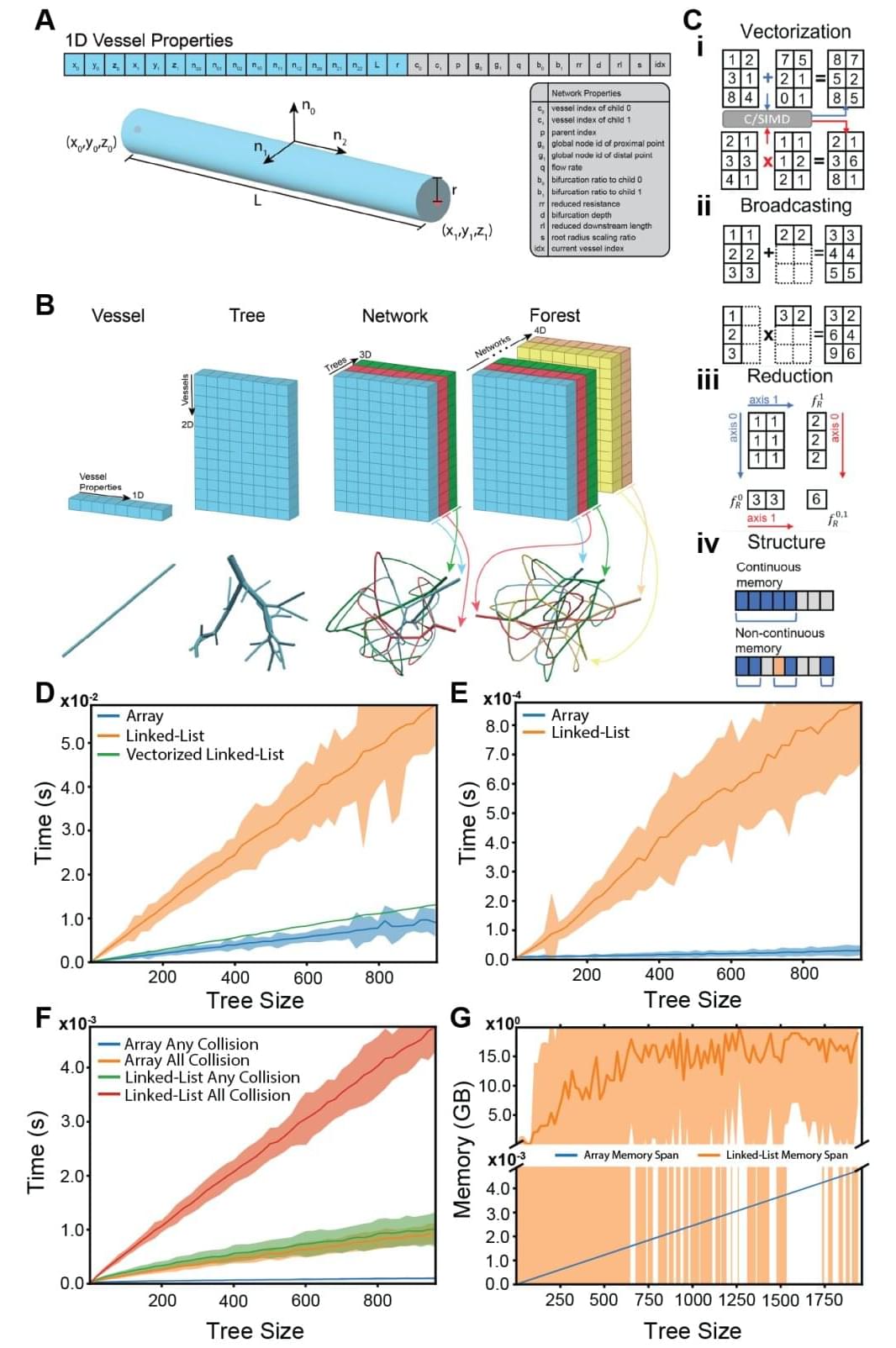

Ensuring that oxygen and nutrients can reach every part of a newly grown organ is an ongoing challenge. Researchers at Stanford have created new tools to design and 3D print the incredibly complex vascular trees needed to carry blood throughout an organ. Their platform, published June 12 in Science, generates designs that resemble what we actually see in the human body significantly faster than previous attempts and is able to translate those designs into instructions for a 3D printer.

“The ability to scale up bioprinted tissues is currently limited by the ability to generate vasculature for them—you can’t scale up these tissues without providing a blood supply,” said Alison Marsden, the Douglas M. and Nola Leishman Professor of Cardiovascular Diseases, professor of pediatrics and of bioengineering at Stanford in the Schools of Engineering and Medicine and co-senior author on the paper. “We were able to make the algorithm for generating the vasculature run about 200 times faster than prior methods, and we can generate it for complex shapes, like organs.”

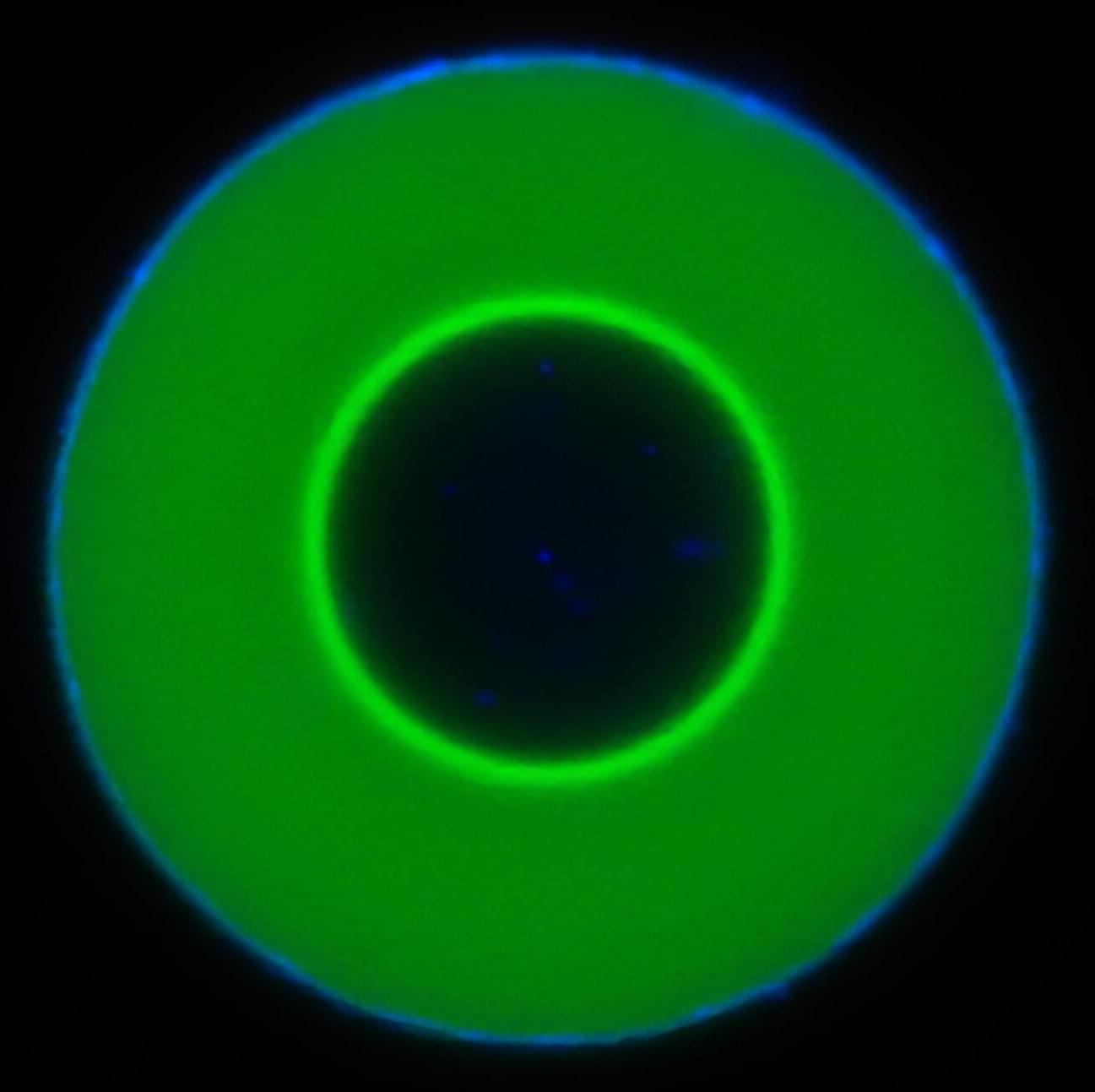

Researchers have identified a form of molecular motion that has not previously been observed. When what are known as “guest molecules”—molecules that are accommodated within a host molecule—penetrate droplets of DNA polymers, they do not simply diffuse in them in a haphazard fashion, but propagate through them in the form of a clearly-defined frontal wave. The team includes researchers from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research and the University of Texas at Austin.

“This is an effect we did not expect at all,” points out Weixiang Chen of the Department of Chemistry at JGU, who played a major role in the discovery. The findings of the research team are published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

The new insights are not only fundamental to our understanding of how cells regulate signals, but they could also contribute to the development of intelligent biomaterials, innovative types of membranes, programmable carriers of active ingredients and synthetic cell systems able to imitate the organizational complexity of the processes in living beings.