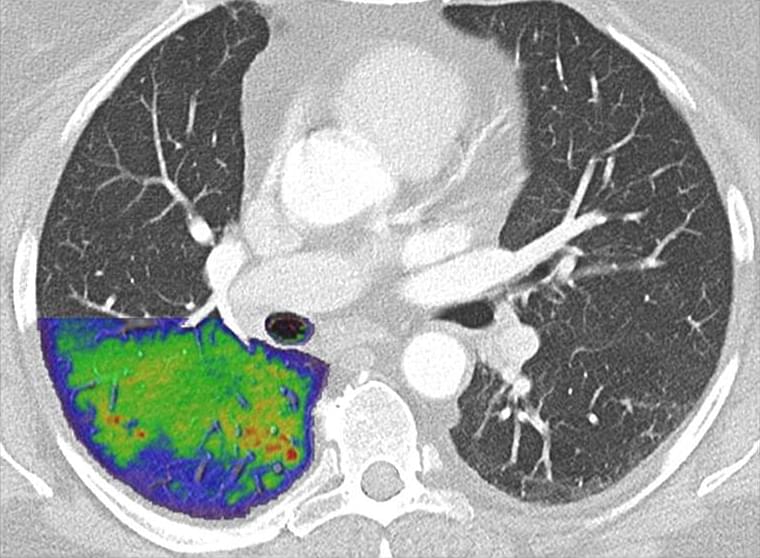

Transforming CT: Naeotom Alpha is the world’s first photon-counting CT scanner. (Courtesy: Siemens.

Magnetic soft robots are systems that can change shape or perform different actions when a magnetic field is applied to them. These robots have numerous advantageous characteristics, including a wireless drive, high flexibility and infinite endurance.

In the future, micro-scale magnetic soft robots could be implemented in a variety of settings; for instance, helping humans to monitor the environment or to remotely perform biomedical procedures. Most of the systems developed so far, however, can only complete simple tasks and take on a limited number of shapes.

Researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences have recently devised a new technique for creating shape-programmable magnetic soft robots. This technique, outlined in a paper pre-published on arXiv and presented at the CCIR2021 conference, allowed them to create a new robot based on magnetic pixels that can change shapes and complete a variety of actions or tasks.

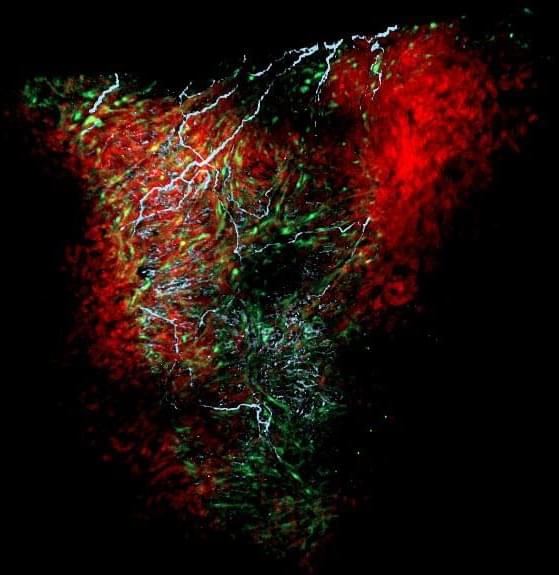

Discovery suggests glial cells may be important in other organs as well.

Glial cells in the heart help regulate heart rate and rhythm, and drive its development in the embryo, according to a new study publishing today (November 18th, 2021) in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Nina Kikel-Coury, Cody Smith and colleagues at the University of Notre Dame. The discovery provides the most detailed portrait yet of a critical population of cells that had been previously poorly understood.

Glia are a diverse set of cell types, originally named after the Greek word for glue, and include cells that surround and nourish neurons, and others that mount immune responses within the central nervous system. In the peripheral nervous system, glia are present and presumably active in multiple organs, including the gut, pancreas, spleen, and lungs, although their function is not clear in most cases.

Over the past few years, scientists have been trying to understand how listening to music affects your brain. One of the features of music that seems to be important is whether you have an emotional connection to it. In other words, listening to a favorite tune will have a different effect on your brain than an unknown or disliked piece of music.

Now, a new study has shown that people with Alzheimer’s Disease can improve their cognition by listening to music that has personal meaning to them, such as songs they’ve been listening to for years.

Researchers Corinne Fischer, Nathan Churchill and colleagues from the University of Toronto ran a small study to find out what exactly happens when people with Alzheimer’s listened to their favorite songs. They asked fourteen people with early stage Alzheimer’s Disease to spend one hour per day listening to music they enjoyed and were very familiar with. Before and after the test period all participants also took a cognitive test, and had their brain activity measured by functional MRI (fMRI).

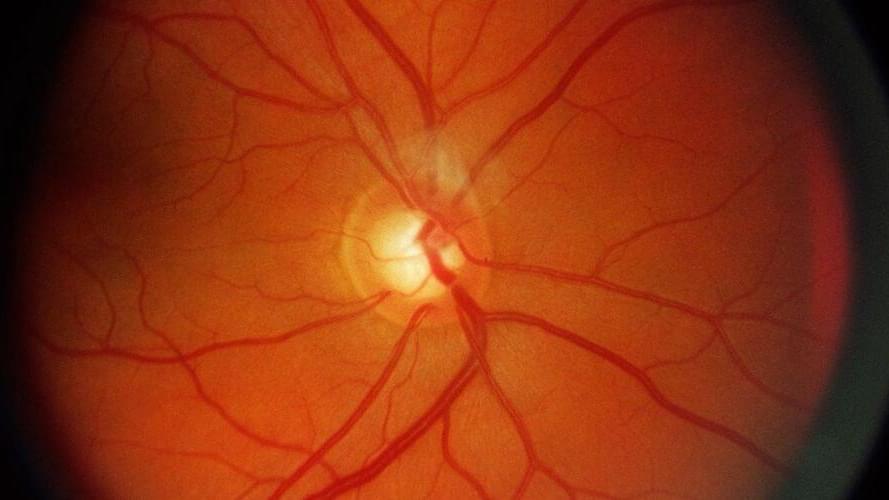

Glaucoma is a surprisingly common condition that can have serious consequences if it goes untreated. Understanding the importance of early detection, a team of engineers and ophthalmologists in Australia has developed a novel approach using AI to diagnose glaucoma that can yield results in just 10 s.

Have you ever experimented with food dye? It can make cooking a lot more fun, and provides a great example of how two fluids can mix together well—or not much at all.

Add a small droplet in water and you might see it slowly dissolve in the larger liquid. Add a few more drops and perhaps you’ll see a wave of color spread, the colored droplets spreading and breaking apart to diffuse more thoroughly. Add a spoon and begin stirring quickly, and you’ll probably find that the water fully changes color, as desired.

Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, led by Ivan Bermejo-Moreno, assistant professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering, studied a similar phenomenon with gases at high speeds, with an eye toward more efficient mixing to support supersonic scramjet engines. In the study, published in Physics of Fluids, USC Viterbi Ph.D. Jonas Buchmeier, along with Xiangyu Gao (USC Viterbi Ph.D. ‘20) and former visiting M.Sc. student Alexander Bußmann (Technical University Munich), developed a novel tracking method that zoomed in on the fundamentals of how mixing happens. The study helps understand, for example, how injected fuel interacts with the surrounding oxidizers (air) in the engine to make it operate optimally, or how interstellar gases mix after a supernova explosion to form new stars. The method focuses on the geometric and physical properties of the turbulent swirling motions of gases and how they change shape over time as they mix.

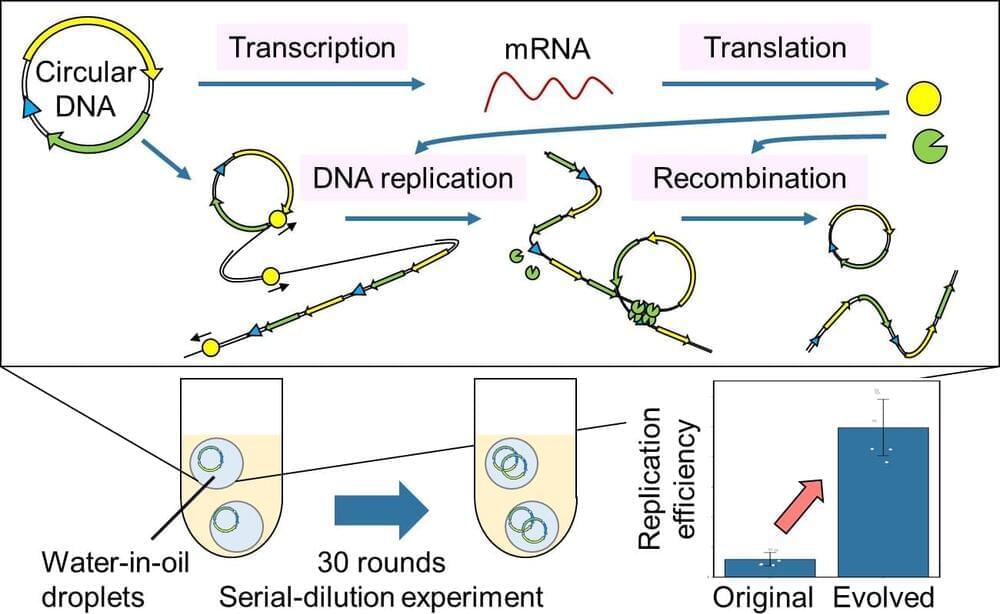

Professor Norikazu Ichihashi and his colleagues at the University of Tokyo have successfully induced gene expression from a DNA, characteristic of all life, and evolution through continuous replication extracellularly using cell-free materials alone, such as nucleic acids and proteins for the first time.

The ability to proliferate and evolve is one of the defining characteristics of living organisms. However, no artificial materials with these characteristics have been created. In order to develop an artificial molecular system that can multiply and evolve, the information (genes) coded in DNA must be translated into RNA, proteins must be expressed, and the cycle of DNA replication with those proteins must continue over a long period in the system. To date, it has been impossible to create a reaction system in which the genes necessary for DNA replication are expressed while those genes simultaneously carry out their function.

The group succeeded in translating the genes into proteins and replicating the original circular DNA with the translated proteins by using a circular DNA carrying two genes necessary for DNA replication (artificial genomic DNA) and a cell-free transcription-translation system. Furthermore, they also successfully improved the DNA to evolve to a DNA with a 10-fold increase in replication efficiency by continuing this DNA replication cycle for about 60 days.

By adding the genes necessary for transcription and translation to the artificial genomic DNA developed by the group, it could be possible to develop artificial cells that can grow autonomously simply by feeding them low-molecular-weight compounds such as amino acids and nucleotides, in the future. If such artificial cells can be created, we can expect that useful substances currently produced using living organisms (such as substances for drug development and food production) will become more stable and easier to control.

This research has been led by Professor Norikazu Ichihashi, a research director of the project “Development of a self-regenerative artificial genome replication-transcription-translation system” in the research area “Large-scale genome synthesis and cell programming” under the JST’s Strategic Basic Research Programs CREST (Team type). In this research area, JST aims to elucidate basic principles in relation to the structure and function of genomes for the creation of a platform technology for the use of cells.

The pandemic brought about a change in the way people look at technology. 2021 proves to be the development of a new era of technology where AI is at the core.

According to McKinsey’s Global Survey on artificial intelligence (AI) 2020, organizations are using AI as a tool for generating value in the form of revenues. Some executives have even observed that implementing AI has brought about a change of 20% in the organizations’ earnings. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the concept of ‘all things digital’, and these companies plan to invest more in AI.

Name: Travis Chen and Brian Femminella

Age: 22 and 21

Location: Seattle, Washington; Los Angeles, California.

Business: SoundMind, a music therapy app designed for those experiencing trauma, depression 0, and anxiety.

Informed consent not something we hear a lot about these days, which is kind of odd, given all the drugs our government currently insists that we take and how often those very same legal concepts are invoked for aboriginal rights and sexual assault cases.

“Informed consent” is a well understood legal doctrine in healthcare, requiring the healthcare provider (traditionally a doctor) to educate patients about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of any given recommended procedure or intervention, allowing the patient to make informed and “voluntary” decisions about whether to undergo the procedure.