And give us customized solutions to problems like disease and pollution.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) remains a major unmet medical challenge, often resulting in permanent paralysis and disability with no effective treatments. Now, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine have harnessed bioinformatics to fast-track the discovery of a promising new drug for SCI. The results will also make it easier for researchers around the world to translate their discoveries into treatments. The findings are published in the journal Nature.

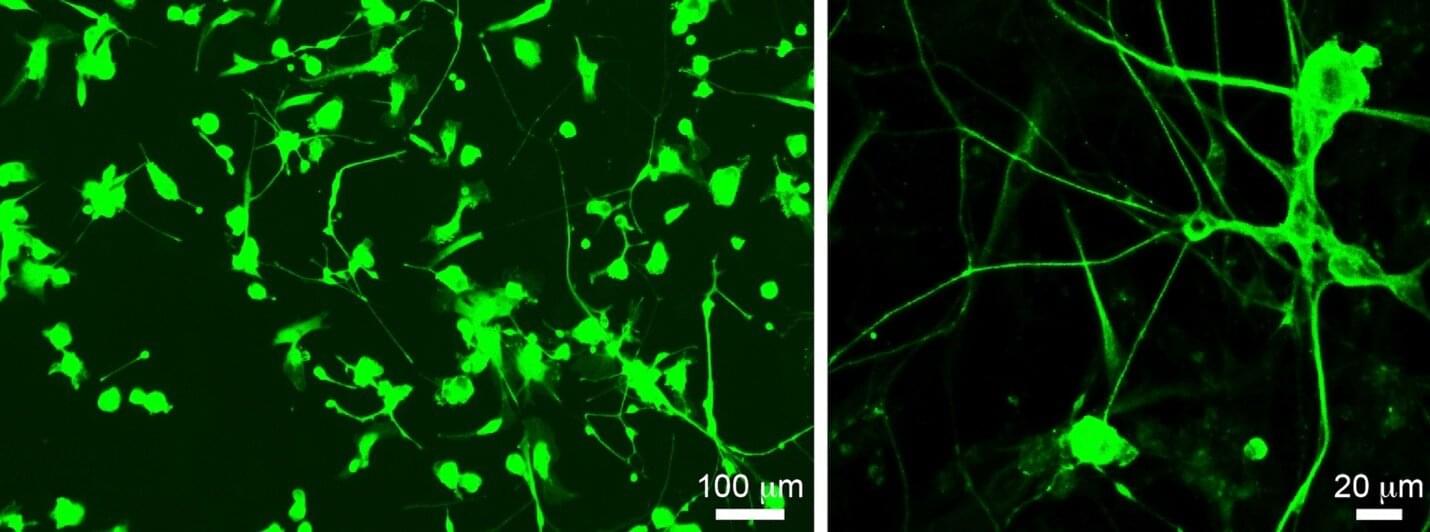

One of the reasons SCI results in permanent disability is that the neurons that form our brain and spinal cord cannot effectively regenerate. Encouraging neurons to regenerate with drugs offers a promising possibility for treating these severe injuries.

The researchers found that under specific experimental conditions, some mouse neurons activate a specific pattern of genes related to neuronal growth and regeneration. To translate this fundamental discovery into a treatment, the researchers used data-driven bioinformatics approaches to compare their pattern to a vast database of compounds, looking for drugs that could activate these same genes and trigger neurons to regenerate.

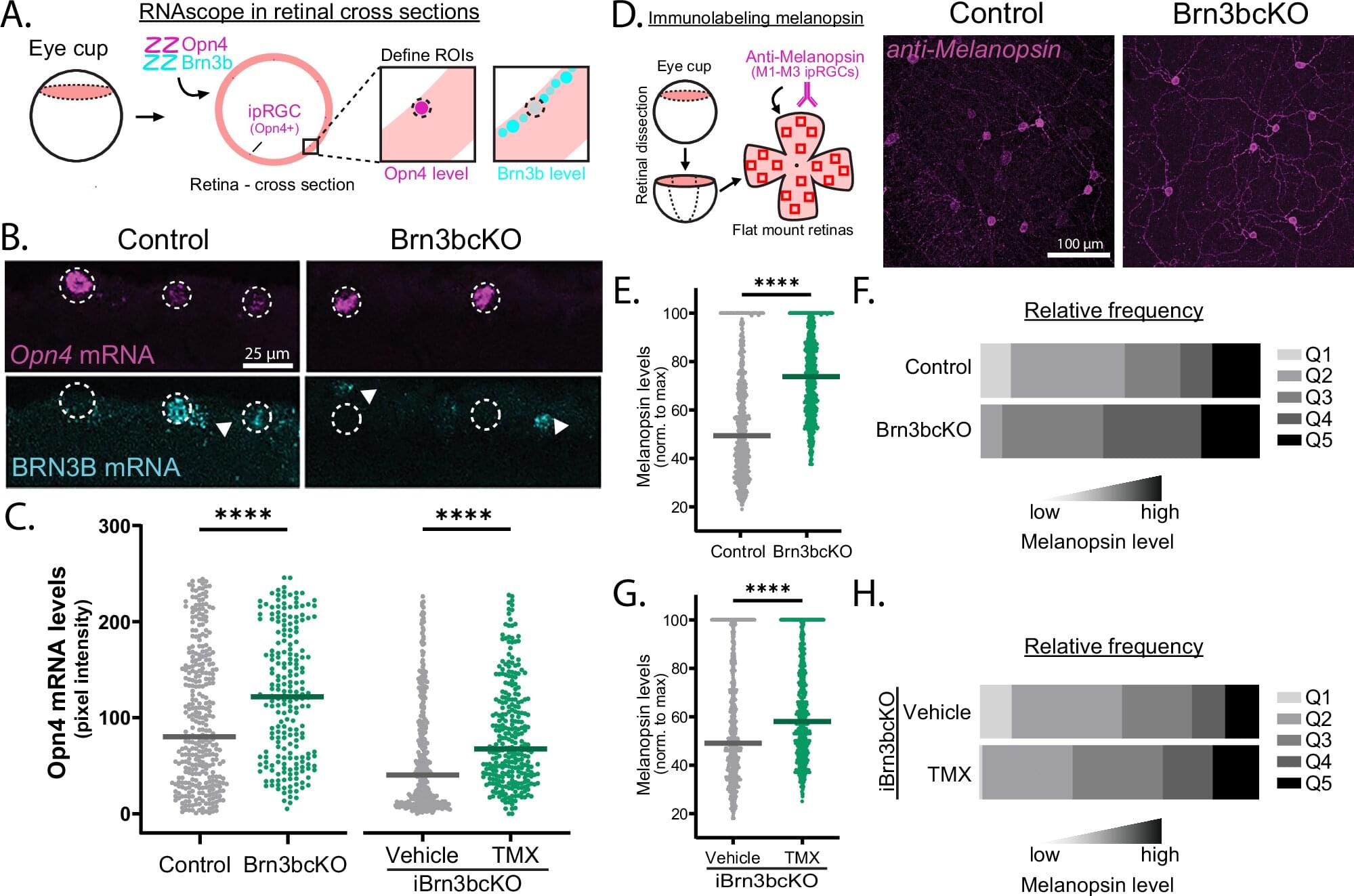

A recent study led by Tiffany Schmidt, Ph.D., associate professor of Ophthalmology and of Neurobiology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, has discovered previously unknown cellular mechanisms that shape neuron identity in retinal cells, findings that may improve the understanding of brain circuitry and disease. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Schmidt’s laboratory studies melanopsin-expressing, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), a type of neuron in the retina that plays a key role in synchronizing the body’s internal clock to the daily light/dark cycle.

There are six subtypes of ipRGCs—M1 to M6—and each expresses a different amount of the protein melanopsin, which makes the ipRGCs directly sensitive to light. However, the mechanisms which give rise to each ipRGCs subtype’s unique structural and functional features have previously remained elusive.

For 25 years, scientists have studied “SuperAgers”—people aged 80 and above whose memory rivals those decades younger. Research reveals that their brains either resist Alzheimer’s-related plaques and tangles or remain resilient despite having them.

These individuals maintain a youthful brain structure, with a thicker cortex and unique neurons linked to memory and social skills. Insights from their biology and behavior could inspire new strategies to protect cognitive health into late life.

For the past 25 years, researchers at Northwestern Medicine have been examining people aged 80 and older, known as “SuperAgers,” to uncover why their minds stay so sharp.

Scientists have identified hundreds of genes that may increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease but the roles these genes play in the brain are poorly understood. This lack of understanding poses a barrier to developing new therapies, but in a study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan NRI) at Texas Children’s Hospital offer new insights into how Alzheimer’s disease risk genes affect the brain.

“We studied fruit fly versions of 100 human Alzheimer’s disease risk genes,” said first author Dr. Jennifer Deger, a neuroscience graduate in Baylor’s Medical Scientist Training Program (M.D./Ph. D.), mentored by Drs. Joshua Shulman and Hugo Bellen.

“We developed fruit flies with mutations that ‘turned off’ each gene and determined how this affected the fly’s brain structure, function and stress resilience as the flies aged.”

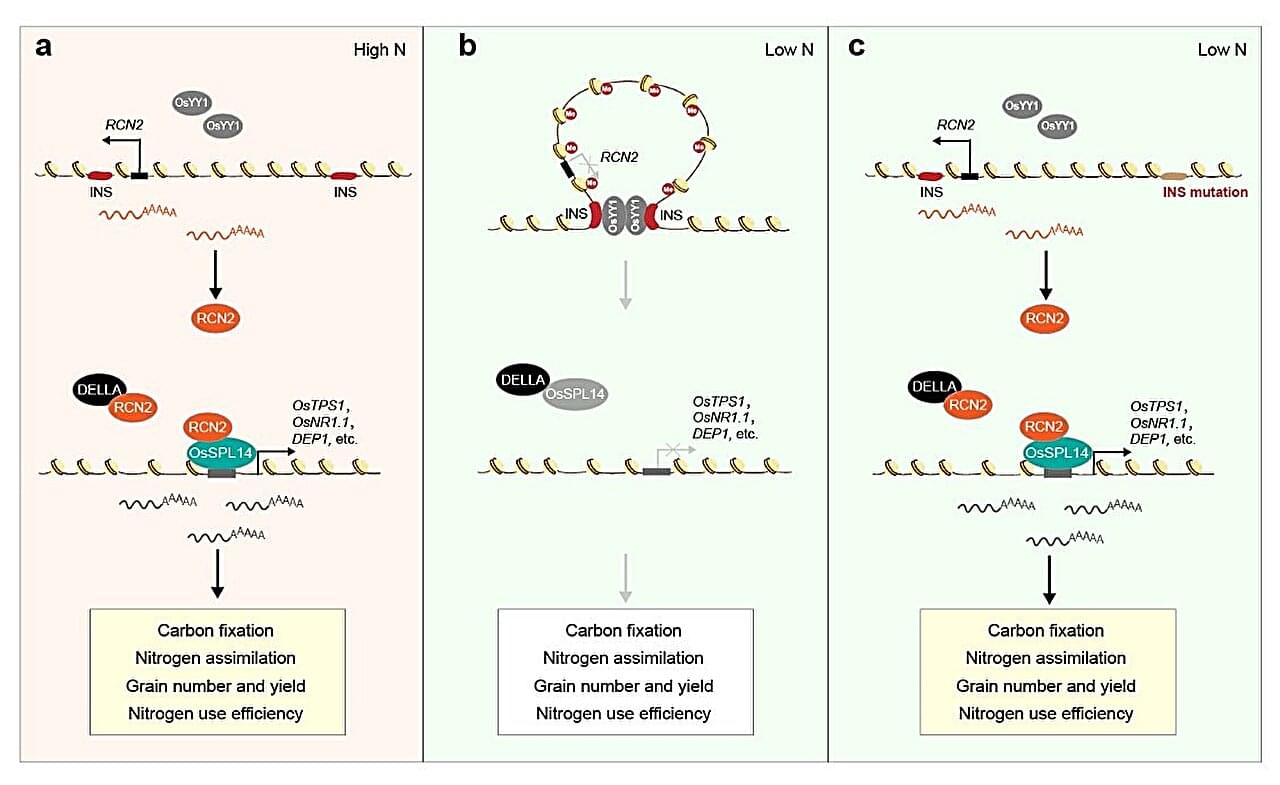

A team of Chinese scientists has uncovered a hidden 3D structure in rice DNA that allows the crop to grow more grain while using less nitrogen fertilizer. The finding, published in Nature Genetics by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), could guide the next “green revolution” toward higher yields and more sustainable farming.

The study reveals that a looping section of DNA—a “chromatin loop”—controls the activity of a gene called RCN2, which governs how rice plants form their grain-bearing branches. Adjusting this loop boosted both yield and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), two traits that normally conflict with each other.

According to Prof. Fu Xiangdong from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of CAS, who led the team, boosting crop yields depends on strengthening both the “source” and the “sink” within a plant. The source refers to tissues such as leaves that produce and release sugars through photosynthesis, while the sink includes the growing parts—grains, panicles, young leaves, stems, roots, and fruits—that store or consume those sugars. Improving both sides of this system simultaneously is essential for increasing yield and NUE.

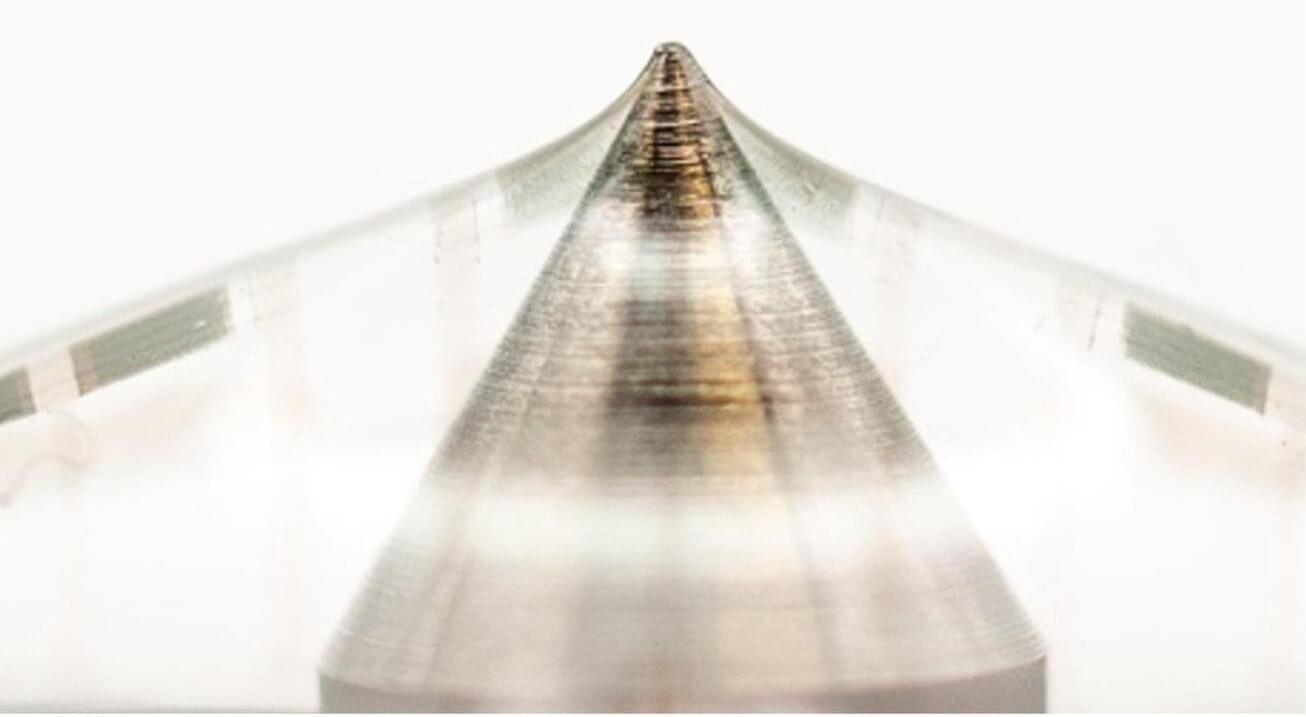

A new method developed at the University of Warwick offers the first simple and predictive way to calculate how irregularly shaped nanoparticles—a dangerous class of airborne pollutant—move through the air.

Every day, we breathe in millions of microscopic particles, including soot, dust, pollen, microplastics, viruses, and synthetic nanoparticles. Some are small enough to slip deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, contributing to conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer.

Most of these airborne particles are irregularly shaped. Yet the mathematical models used to predict how these particles behave typically assume they are perfect spheres, simply because the equations are easier to solve. This makes it difficult to monitor or predict the movement of real-world, non-spherical—and often more hazardous—particles.

The rapid advancement of sensing and artificial intelligence (AI) systems has paved the way for the introduction of increasingly sophisticated wearable devices, such as fitness trackers and technologies that closely monitor signals associated with specific diseases or medical conditions. Many of these wearable electronics rely on so-called biosensors, devices that can convert biological responses into measurable electrical signals in real-time.

While fitness trackers and other wearable electronics are now widely used, the signals that many existing devices pick up are sometimes inaccurate or distorted. This is because the bending of sensors, moisture and temperature fluctuations sometimes produce inaccurate readings and drifts (i.e., gradual changes that are unrelated to a measured signal).

Researchers at Stanford University have developed new skin-inspired biosensors based on organic field effect transistors (OFETs), devices based on organic semiconductors that control the flow of current in electronics.