http://www.blogtalkradio.com/biteradiome/2018/01/03/bioquark…a-s-pastor

The future of cancer care should mean more cost-effective treatments, a greater focus on prevention, and a new mindset: A Surgical Oncologist’s take

Multidisciplinary team management of many types of cancer has led to significant improvements in median and overall survival. Unfortunately, there are still other cancers which we have impacted little. In patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and hepatocellular cancer, we have been able to improve median survival only by a matter of a few months, and at a cost of toxicity associated with the treatments. From the point of view of a surgical oncologist, I believe there will be rapid advances over the next several decades.

Robotic Surgery

There is already one surgery robot system on the market and another will soon be available. The advances in robotics and imaging have allowed for improved 3-dimensional spacial recognition of anatomy, and the range of movement of instruments will continue to improve. Real-time haptic feedback may become possible with enhanced neural network systems. It is already possible to perform some operations with greater facility, such as very low sphincter-sparing operations for rectal adenocarcinoma in patients who previously would have required a permanent colostomy. As surgeons’ ability and experience with new robotic equipment becomes greater, the number and types of operation performed will increase and patient recovery time, length of hospital stay, and return to full functional status will improve. Competition may drive down the exorbitant cost of current equipment.

More Cost Effective Screening

The mapping of the human genome was a phenomenal project and achievement. However, we still do not understand the function of all of the genes identified or the complex interactions with other molecules in the nucleus. We also forget that cancer is a perfect experiment in evolutionary biology. Once cancer has developed, we begin treatments with cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs, targeted agents, immunotherapies, and ionizing radiation. Many of the treatments are themselves mutagenic, and place selection pressure on cells with beneficial mutations allowing them to evade response or repair damage caused by the treatment, survive, multiply, and metastasize. In some patients who are seeming success stories, new cancers develop years or decades later, induced by our therapies to treat their initial cancer. Currently, we place far too little emphasis on screening and prevention of cancer. Hopefully, in the not too distant future, screening of patients with simple, readily available, and inexpensive blood tests looking at circulating cells and free DNA may allow us to recognize patients at high risk to develop certain malignancies, or to detect cancer at far earlier stages when surgical and other therapies have a higher probability of success.

Changing the Mindset

A diagnosis of cancer incites fear and uncertainty in patients and their family members. Many feel they are receiving a certain death sentence. While we have improved the probability of long-term success with some cancers, there are others where we have simply shifted the survival curve to produce a few more months of survival before the patient succumbs. We need to adopt strategies that allow us to contain and control malignant disease without necessarily eradicating it. If a tumor or tumors are in a dormant or senescent state and not causing symptoms or problems, minimally toxic treatments stopping tumor growth and progression allowing the patient to live a normal and productive life would be a success. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes are never “cured” of their diabetes, but with proper medical management their disease can be controlled and they can survive and function without any of the negative consequences and sequelae of the disease. If we can understand genetic signaling and aberrations sufficiently, perhaps we can control cancer for long periods while maintaining a high quality of life for our patients.

Taking on Tough Political Issues

I am often asked by patients if I believe there will ever be a “cure” for cancer. I invariably reply it is unlikely if we continue to engage in activities and behaviors which increase the likelihood of developing cancer. Cigarette smoking, smokeless tobacco use, excess alcohol or food intake, lack of exercise, and pollution of the environment around us produce carcinogens or conditions increasing the risk of cancer development. Unless we find the courage and strength to limit access or ban substances that are known carcinogens, like cigarettes, and begin as thoughtful citizens of the planet behaving in a more responsible fashion to eliminate air, ground, and water pollution, we will not make a significant impact on the incidence of cancer. We must also be willing to develop greater and more far reaching population education programs about things as simple as proper ultraviolet light protection during sun exposure, and to recognize tanning beds or excessive, unprotected natural sunlight exposure increases the risk of a particularly difficult and vicious malignancy, melanoma. Whether we like to admit it or not, humans respond to societal pressures and images displayed or touted by media, marketing firms, or so-called beauty and glamor outlets that may actually be harmful to the health of the populace. People do and should have a free will, but they should also be given understandable, honest, and rational information on the potential consequences of their choices. There should also be a higher level of personal accountability and responsibility for negative outcomes based on an individual’s choices.

Global Cancer Care

It is estimated that between half and two thirds of the world’s population, particularly in poor or developing countries, have limited or no access to cancer prevention, screening, or care. The improved outcomes we report in medical and surgical journals from advanced countries assume the treatment can be paid for and access is available to all. Nothing is further from the truth. Meaningful efforts to rein in the rampant increases in cancer drug costs, reduce the prohibitively long and expensive process to develop and approve a novel treatment, and to provide training and education for practitioners in developing countries must be made. The disparities even within the United States are great, and it is well known and documented that disadvantage populations are often diagnosed with later stage disease, and generally have reduced chances of long-term success with the treatments available. We must become inclusive, not exclusive, in our worldview and through outreach and development programs begin to build infrastructure and access to affordable care worldwide.

Thinking Outside the Box

Personalized or individualized patient cancer care is a popular buzz phrase these days. In reality, we currently have very few drugs or targeted agents to act upon the numerous genetic or epigenetic abnormalities present in the average cancer. To search for drugs to new targets or abnormal pathways, we must create a system where there is rapid assessment, cost effectiveness, and streamlined regulatory approval for patients with lethal diseases. Personalized cancer treatment is not affordable without major changes in policy and practice. We should recognize malignant tumors have interesting physicochemical and electrical properties different from the normal tissues from which they arise. Therapy with electromagnetic fields specifically tailored to a given patient’s tumor properties can enhance tumor blood flow and improve delivery of drugs or agents while reducing toxicity and side effects. Developing approaches that do not produce acute and long-term side effects or an increased risk to develop second malignancies must be a priority.

Science and technology information is being produced at an incomprehensible rate. We need help from specialized colleagues with big data management and recognition of trends and developments which can be quickly disseminated throughout the medical community, and to appropriate patient populations. All of these measures require commitment and dedication to changing the way we think, reversing priorities based far too much on profitability of treatments rather than availability and affordability of treatment, and we cannot ignore the importance of programs to improve cancer prevention, screening, and early diagnosis.

Philadelphia, PA, USA / Mexico City, Mexico — Bioquark, Inc., (www.bioquark.com) a life sciences company focused on the development of novel bioproducts for complex regeneration, disease reversion, and aging, and RegenerAge SAPI de CV, (www.regenerage.clinic/en/) a clinical company focused on translational therapeutic applications of a range of regenerative and rejuvenation healthcare interventions, have announced a collaboration to focus on novel combinatorial approaches in human disease and wellness. SGR-Especializada (http://www.sgr-especializada.com/), regulatory experts in the Latin American healthcare market, assisted in the relationship.

“We are very excited about this collaboration with RegenerAge SAPI de CV,” said Ira S. Pastor, CEO, Bioquark Inc. “The natural synergy of our cellular and biologic to applications of regenerative and rejuvenative medicine will make for novel and transformational opportunities in a range of degenerative disorders.”

As we close in on $7 trillion in total annual health care expenditures around the globe ($1 trillion spent on pharmaceutical products; $200 billion on new R&D), we are simultaneously witnessing a paradoxical rise in the prevalence of all chronic degenerative diseases responsible for human suffering and death.

With the emergence of such trends including: personalization of medicine on an “n-of-1” basis, adaptive clinical design, globalization of health care training, compassionate use legislative initiatives for experimental therapies, wider acceptance of complementary medical technologies, and the growth of international medical travel, patients and clinicians are more than ever before, exploring the ability to access the therapies of tomorrow, today.

The estimate of the current market size for procedural medical travel, defined by medical travelers who travel across international borders for the purpose of receiving medical care, is in the range of US $40–55 billion.

Additionally, major clinical trial gaps currently exist across all therapeutic segments that are responsible for human suffering and death. Cancer is one prime example. As a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide for many decades, today there are approximately 14 million new cases diagnosed each year, with over 8 million cancer related deaths annually. It is estimated that less than 5% of these patients, take the initiative to participate in any available clinical studies.

“We look forward to working closely with Bioquark Inc. on this exciting initiative,” said Dr. Joel Osorio, Chief of Clinical Development RegenerAge SAPI de CV. “The ability to merge cellular and biologic approaches represents the next step in achieving comprehensive regeneration and disease reversion events in a range of chronic diseases responsible for human suffering and death.”

About Bioquark, Inc.

Bioquark Inc. is focused on the development of natural biologic based products, services, and technologies, with the goal of curing a wide range of diseases, as well as effecting complex regeneration. Bioquark is developing both biological pharmaceutical candidates, as well as products for the global consumer health and wellness market segments.

About RegenerAge SAPI de CV

RegenerAge SAPI de CV is a novel clinical company focused on translational therapeutic applications, as well as expedited, experimental access for “no option” patients, to a novel range of regenerative and reparative biomedical products and services, with the goal of reducing human degeneration, suffering, and death.

Fox 29 — Good Day Philadelphia

http://www.fox29.com/140735577-video

NBC TV 10

http://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/local/Zombies-from-Phill…65101.html

CNN en Espanol

http://cnnespanol.cnn.com/video/cnnee-encuentro-intvw-joel-o…-cerebral/

I learn useful life lessons from each patient I meet. Some are positive messages, reminding me of the importance of maintaining balance between family, work, and leisure activities, but more frequently I witness examples of the remarkable resilience of the human spirit when facing the reality and risks of a major surgical procedure and a diagnosis of cancer. Rarely, patients and their family members utter remorseful or simply sad remarks when they are faced with a grim prognosis and the emotions associated with an onrushing date with mortality. These comments invariably involve an inventory of regrets in life, including, “I should have spent more time with my kids,” “I wish I had told my father (or mother, brother, sister, child, or some other person) that I loved them before they died,” and “I have spent my entire life working, I never took time for anything else.” I wince when I hear these openly expressed remonstrations, I recognize that I am hearing painful and heartfelt truths. Not a week goes by that I am not reminded that I do not one day want to look back at my life with a long list of regrets, should have dones, and what ifs.

I was blessed to meet a great teacher in the guise of a patient early in my academic career. He came to my clinic in my first year after completing a Fellowship in Surgical Oncology, my first year as an Assistant Professor of Surgery. My patient was a 69 year-old Baptist Minister from a small town in Mississippi. He was referred to me by his medical oncologist who called me and said, “I don’t think there is anything you can do for him, but he needs to hear that from you because he doesn’t believe me.” This tall, imposing man had colon cancer that had metastasized (spread) to his liver. The malignant tumor in his colon was removed the year before I met him, and he had received chemotherapy to treat several large tumors found in his liver. The chemotherapy had not worked and the tumors grew. At the point I met him, the medical oncologist told him he would live no more than 6 months, and because he was an avid fisherman when not preaching or helping others in his community , the doctor suggested that he go out and enjoy his remaining time by getting in as much fishing as possible. I learned two invaluable lessons from this patient and his family. First, never deny or dismiss hope from a patient or their family, even when from a medical perspective the situation seems hopeless and the patient is incurable. Second, quoting the minister directly, “Some doctors think of themselves as gods with a small ‘g’, but not one of you is God”.

When I first walked into the examining room, this man was slouched on the examining table in the perfunctory blue and white, open-backed, always unflattering hospital gown. He made eye contact with me briefly, then looked down to the floor. In that momentary meeting of our eyes, I saw no sparkle, no life, no hope in his eyes. He responded to my initial questions with a monotonic and quiet voice. Several times I had to ask him to repeat an answer because his response was so muted. Mid-way through our first visit, the patient’s wife told me he had been very depressed by his diagnosis of untreatable metastatic colon cancer. She reported, despite his occasional side-long warning glances requesting her silence, that while he was eating well, he was spending most of his time sitting in a chair or laying in bed, and that the active, gregarious man with the quick wit and booming voice she had married was gone.

After I interviewed and examined the Minister I left the room so he could dress and sit in a chair next to his wife. I reviewed the results of the lab tests and CT scans we had performed on him, and then returned to the examining room. I explained to them that I believed it was possible to perform a difficult operation that would remove approximately 80% of his liver. The operation would be risky, it was possible he would require blood transfusions, and as a worst-case scenario the small amount of remaining liver might not be sufficient to perform necessary functions. If I pushed the surgical envelope too far and removed too much normal liver, following the operation he could develop liver failure leading rapidly to his death. I also stated, assuming he survived a major operation and the recovery period, that I could not predict his long-term outcome or survival. I emphasized that even if the operation was successful, it was possible that the cancer would recur in the remaining liver or in some other organ. I even attempted to raise his spirits a bit by injecting some puerile surgical word play when I said, “This operation will leave you with little more than a sliver of liver, but God willing it will be enough!” At the conclusion of my very direct monologue, he looked up from the floor and once again his eyes met mine. I remember blinking several times in surprise at how different his eyes now appeared. With his eyes bright and twinkling he asked, “Are you saying there is hope?” I replied that I believed there was hope, albeit small and impossible to measure, but hope nonetheless. An unforgettable and immediate transformation occurred in his demeanor and as his wife smiled at me and mouthed the words, “He’s back”; he reverted instantaneously to what I would come to learn was his former garrulous self.

The spiritually-resuscitated Minister sat upright, grasped my right hand with both of his hands, and launched into a memorable diatribe. “Never deny someone hope doctor, no matter how hopeless you know the situation to be. Humans need hope, without it comes depression, despair, and death. Why do you think the Jewish defenders at Masada held out against an overwhelming Roman force for so long? Because they had hope, and they had faith. Why do people let you cut them open? Hope. Never deny a human being hope doctor, without it we have no humanity, we are only another animal.” He was a forceful and eloquent speaker. With his Mississippi drawl, he could alternatively be plain spoken or pedantic. He was a well-read and educated man and he loved to display his extensive etymologic armamentarium. Not infrequently after our conversations I would seek out a dictionary to learn the meaning of a word or two. I had no difficulty visualizing him preaching from a pulpit in his Baptist church, like a yo-yo dropping his parishioners to the floor with the fear of eternal damnation, and then pulling them back up into his hands with a message of redemption and salvation.

I walked out of the examination room enthralled and scheduled the operation for the next week. I was amazed by the sudden change I had witnessed in this man’s posture and overall demeanor. As with all who provide care for patients with debilitating and serious medical conditions, I have seen patients lapse into a state of abject, deep despair and complete hopelessness. Like an autumn leaf falling from a tree branch, their spiritual demise leads to a rapid downward spiral of their physical condition. These patients fulfill the expectations of medical practitioners who have told them their survival will be a matter of only weeks or months, in fact I have seen several patients die much more rapidly than I would have predicted when darkness and despair overwhelmed them.

I had the Minister’s “sermon” on my mind throughout his operation. As I expected, the operation was technically difficult. He was a robust, barrel-chested man and had four large tumors in his liver. Two of these were right lobe of the liver only, but the other two extended from the right lobe of his liver into portions of the left lobe of the liver. One of these latter two tumors also extended down to involve two of the three large veins that drain blood from the liver into the large vein, called the inferior vena cava, that carries blood back to the heart. To assure that I had completely removed all of the tumor around these two veins, I removed a portion of the wall of the inferior vena cava and replaced it with a patch from another vein. It was a liver surgery tour-de-force, and at the conclusion of the operation the surgical fellow who performed the operation with me and I quietly congratulated one another on a job well done. Nonetheless, I admit to my own negative sentiments and relative paucity of optimism at the end of the operation. I remarked to the surgical fellow working with me that while the operation had been technically challenging and a great lesson in surgical anatomy, I doubted that we had cured this patient because I was concerned his aggressive cancer would return.

“Never deny someone hope doctor.” If I ever had a crystal ball to predict the future, I obviously dropped it in the mud a long time ago. I was wrong about the Minister. His cancer never returned. He spent only one week in the hospital after his operation and his sliver of liver performed and regenerated beautifully. For the first five years after the operation I saw him every three to six months with lab tests and CT scans to check for return of malignant tumors. For the next six years I saw him only for an annual visit. This man survived and enjoyed life for eleven years after being told that he only had only six months to live. He died as many of us would wish to die, in his sleep from a stroke. He gave his last sermon from the pulpit of his church three days before he died. His cancer never returned to prey upon his mind and hunt down his hope.

After thinking about it, I realize I learned one additional lesson from this patient. He taught me that it was acceptable to express a little clean, righteous anger and then laugh and move on. The Minister and I developed a ritual that was repeated with each of his visits after passage of the initial six months he was told he would live by his medical oncologist. After I reviewed the results of his tests and CT scans and confirmed that all was well and that cancer had not returned, he would smile and say, “Let’s do it!” From the examining room, I would dial the phone number of the medical oncologist in Mississippi who had referred him to me. The Minister admitted to me he was angry that this doctor had needlessly denied him hope. When the medical oncologist came to the phone, I would hand it to the Minister, who would identify himself to the doctor, and then he would say the same exact words, “Hey doc, you want to go fishing?” As a surgeon, I confess I enjoyed witnessing the surgical precision with which the preacher inserted this verbal blade, deftly turning it to maximize the impact of his statement. When I passed the phone to the Minister, he always had an impish, perhaps even devilish grin on his face. Each time after he asked the doctor in Mississippi if he would care to join him for a fishing expedition, he would hand the phone back to me and a look of beatific serenity would come to his face. The ritual was completed when I would take the phone and speak to the doctor in Mississippi. In my first few conversations with this physician, I apologized for my obvious and indecorous breach in professional behavior, but to the credit of this man being regularly taunted by a Baptist Minister who wasn’t entirely forgiving, he would tell me that no apology was necessary and that he believed he deserved and benefited from these brief but poignant verbal reminders. As the years passed, he would be laughing when I put the phone to my ear and tell me that he really enjoyed those calls and that his whole office staff looked forward to this annual event.

Two years before the Minister finally died at the age of 80, the doctor in Mississippi told me that because of this patient, he never answered the question asked to him by patients about their expected longevity with a diagnosis of advanced cancer. Instead, he would inform the patients and their families that he really couldn’t make such a prediction because of marked individual differences in responses to treatment, along with the immeasurable will to live even in individuals no longer receiving treatment for their cancer. Together, he and I learned the importance of leaving no treatment stone unturned; to engage in multidisciplinary management and to consider all options for our patients. Great lessons from a great spiritual teacher, taught to a couple of hard-headed doctors.

“Hey doc, you want to go fishing?”

I learn useful life lessons from each patient I meet. Some are positive messages, reminding me of the importance of maintaining balance between family, work, and leisure activities, but more frequently I witness examples of the remarkable resilience of the human spirit when facing the reality and risks of a major surgical procedure and a diagnosis of cancer. Rarely, patients and their family members utter remorseful or simply sad remarks when they are faced with a grim prognosis and the emotions associated with an onrushing date with mortality. These comments invariably involve an inventory of regrets in life, including, “I should have spent more time with my kids,” “I wish I had told my father (or mother, brother, sister, child, or some other person) that I loved them before they died,” and “I have spent my entire life working, I never took time for anything else.” I wince when I hear these openly expressed remonstrations, I recognize that I am hearing painful and heartfelt truths. Not a week goes by that I am not reminded that I do not one day want to look back at my life with a long list of regrets, should have dones, and what ifs.

I was blessed to meet a great teacher in the guise of a patient early in my academic career. He came to my clinic in my first year after completing a Fellowship in Surgical Oncology, my first year as an Assistant Professor of Surgery. My patient was a 69 year-old Baptist Minister from a small town in Mississippi. He was referred to me by his medical oncologist who called me and said, “I don’t think there is anything you can do for him, but he needs to hear that from you because he doesn’t believe me.” This tall, imposing man had colon cancer that had metastasized (spread) to his liver. The malignant tumor in his colon was removed the year before I met him, and he had received chemotherapy to treat several large tumors found in his liver. The chemotherapy had not worked and the tumors grew. At the point I met him, the medical oncologist told him he would live no more than 6 months, and because he was an avid fisherman when not preaching or helping others in his community , the doctor suggested that he go out and enjoy his remaining time by getting in as much fishing as possible. I learned two invaluable lessons from this patient and his family. First, never deny or dismiss hope from a patient or their family, even when from a medical perspective the situation seems hopeless and the patient is incurable. Second, quoting the minister directly, “Some doctors think of themselves as gods with a small ‘g’, but not one of you is God”.

When I first walked into the examining room, this man was slouched on the examining table in the perfunctory blue and white, open-backed, always unflattering hospital gown. He made eye contact with me briefly, then looked down to the floor. In that momentary meeting of our eyes, I saw no sparkle, no life, no hope in his eyes. He responded to my initial questions with a monotonic and quiet voice. Several times I had to ask him to repeat an answer because his response was so muted. Mid-way through our first visit, the patient’s wife told me he had been very depressed by his diagnosis of untreatable metastatic colon cancer. She reported, despite his occasional side-long warning glances requesting her silence, that while he was eating well, he was spending most of his time sitting in a chair or laying in bed, and that the active, gregarious man with the quick wit and booming voice she had married was gone.

After I interviewed and examined the Minister I left the room so he could dress and sit in a chair next to his wife. I reviewed the results of the lab tests and CT scans we had performed on him, and then returned to the examining room. I explained to them that I believed it was possible to perform a difficult operation that would remove approximately 80% of his liver. The operation would be risky, it was possible he would require blood transfusions, and as a worst-case scenario the small amount of remaining liver might not be sufficient to perform necessary functions. If I pushed the surgical envelope too far and removed too much normal liver, following the operation he could develop liver failure leading rapidly to his death. I also stated, assuming he survived a major operation and the recovery period, that I could not predict his long-term outcome or survival. I emphasized that even if the operation was successful, it was possible that the cancer would recur in the remaining liver or in some other organ. I even attempted to raise his spirits a bit by injecting some puerile surgical word play when I said, “This operation will leave you with little more than a sliver of liver, but God willing it will be enough!” At the conclusion of my very direct monologue, he looked up from the floor and once again his eyes met mine. I remember blinking several times in surprise at how different his eyes now appeared. With his eyes bright and twinkling he asked, “Are you saying there is hope?” I replied that I believed there was hope, albeit small and impossible to measure, but hope nonetheless. An unforgettable and immediate transformation occurred in his demeanor and as his wife smiled at me and mouthed the words, “He’s back”; he reverted instantaneously to what I would come to learn was his former garrulous self.

The spiritually-resuscitated Minister sat upright, grasped my right hand with both of his hands, and launched into a memorable diatribe. “Never deny someone hope doctor, no matter how hopeless you know the situation to be. Humans need hope, without it comes depression, despair, and death. Why do you think the Jewish defenders at Masada held out against an overwhelming Roman force for so long? Because they had hope, and they had faith. Why do people let you cut them open? Hope. Never deny a human being hope doctor, without it we have no humanity, we are only another animal.” He was a forceful and eloquent speaker. With his Mississippi drawl, he could alternatively be plain spoken or pedantic. He was a well-read and educated man and he loved to display his extensive etymologic armamentarium. Not infrequently after our conversations I would seek out a dictionary to learn the meaning of a word or two. I had no difficulty visualizing him preaching from a pulpit in his Baptist church, like a yo-yo dropping his parishioners to the floor with the fear of eternal damnation, and then pulling them back up into his hands with a message of redemption and salvation.

I walked out of the examination room enthralled and scheduled the operation for the next week. I was amazed by the sudden change I had witnessed in this man’s posture and overall demeanor. As with all who provide care for patients with debilitating and serious medical conditions, I have seen patients lapse into a state of abject, deep despair and complete hopelessness. Like an autumn leaf falling from a tree branch, their spiritual demise leads to a rapid downward spiral of their physical condition. These patients fulfill the expectations of medical practitioners who have told them their survival will be a matter of only weeks or months, in fact I have seen several patients die much more rapidly than I would have predicted when darkness and despair overwhelmed them.

I had the Minister’s “sermon” on my mind throughout his operation. As I expected, the operation was technically difficult. He was a robust, barrel-chested man and had four large tumors in his liver. Two of these were right lobe of the liver only, but the other two extended from the right lobe of his liver into portions of the left lobe of the liver. One of these latter two tumors also extended down to involve two of the three large veins that drain blood from the liver into the large vein, called the inferior vena cava, that carries blood back to the heart. To assure that I had completely removed all of the tumor around these two veins, I removed a portion of the wall of the inferior vena cava and replaced it with a patch from another vein. It was a liver surgery tour-de-force, and at the conclusion of the operation the surgical fellow who performed the operation with me and I quietly congratulated one another on a job well done. Nonetheless, I admit to my own negative sentiments and relative paucity of optimism at the end of the operation. I remarked to the surgical fellow working with me that while the operation had been technically challenging and a great lesson in surgical anatomy, I doubted that we had cured this patient because I was concerned his aggressive cancer would return.

“Never deny someone hope doctor.” If I ever had a crystal ball to predict the future, I obviously dropped it in the mud a long time ago. I was wrong about the Minister. His cancer never returned. He spent only one week in the hospital after his operation and his sliver of liver performed and regenerated beautifully. For the first five years after the operation I saw him every three to six months with lab tests and CT scans to check for return of malignant tumors. For the next six years I saw him only for an annual visit. This man survived and enjoyed life for eleven years after being told that he only had only six months to live. He died as many of us would wish to die, in his sleep from a stroke. He gave his last sermon from the pulpit of his church three days before he died. His cancer never returned to prey upon his mind and hunt down his hope.

After thinking about it, I realize I learned one additional lesson from this patient. He taught me that it was acceptable to express a little clean, righteous anger and then laugh and move on. The Minister and I developed a ritual that was repeated with each of his visits after passage of the initial six months he was told he would live by his medical oncologist. After I reviewed the results of his tests and CT scans and confirmed that all was well and that cancer had not returned, he would smile and say, “Let’s do it!” From the examining room, I would dial the phone number of the medical oncologist in Mississippi who had referred him to me. The Minister admitted to me he was angry that this doctor had needlessly denied him hope. When the medical oncologist came to the phone, I would hand it to the Minister, who would identify himself to the doctor, and then he would say the same exact words, “Hey doc, you want to go fishing?” As a surgeon, I confess I enjoyed witnessing the surgical precision with which the preacher inserted this verbal blade, deftly turning it to maximize the impact of his statement. When I passed the phone to the Minister, he always had an impish, perhaps even devilish grin on his face. Each time after he asked the doctor in Mississippi if he would care to join him for a fishing expedition, he would hand the phone back to me and a look of beatific serenity would come to his face. The ritual was completed when I would take the phone and speak to the doctor in Mississippi. In my first few conversations with this physician, I apologized for my obvious and indecorous breach in professional behavior, but to the credit of this man being regularly taunted by a Baptist Minister who wasn’t entirely forgiving, he would tell me that no apology was necessary and that he believed he deserved and benefited from these brief but poignant verbal reminders. As the years passed, he would be laughing when I put the phone to my ear and tell me that he really enjoyed those calls and that his whole office staff looked forward to this annual event.

Two years before the Minister finally died at the age of 80, the doctor in Mississippi told me that because of this patient, he never answered the question asked to him by patients about their expected longevity with a diagnosis of advanced cancer. Instead, he would inform the patients and their families that he really couldn’t make such a prediction because of marked individual differences in responses to treatment, along with the immeasurable will to live even in individuals no longer receiving treatment for their cancer. Together, he and I learned the importance of leaving no treatment stone unturned; to engage in multidisciplinary management and to consider all options for our patients. Great lessons from a great spiritual teacher, taught to a couple of hard-headed doctors.

“Hey doc, you want to go fishing?”

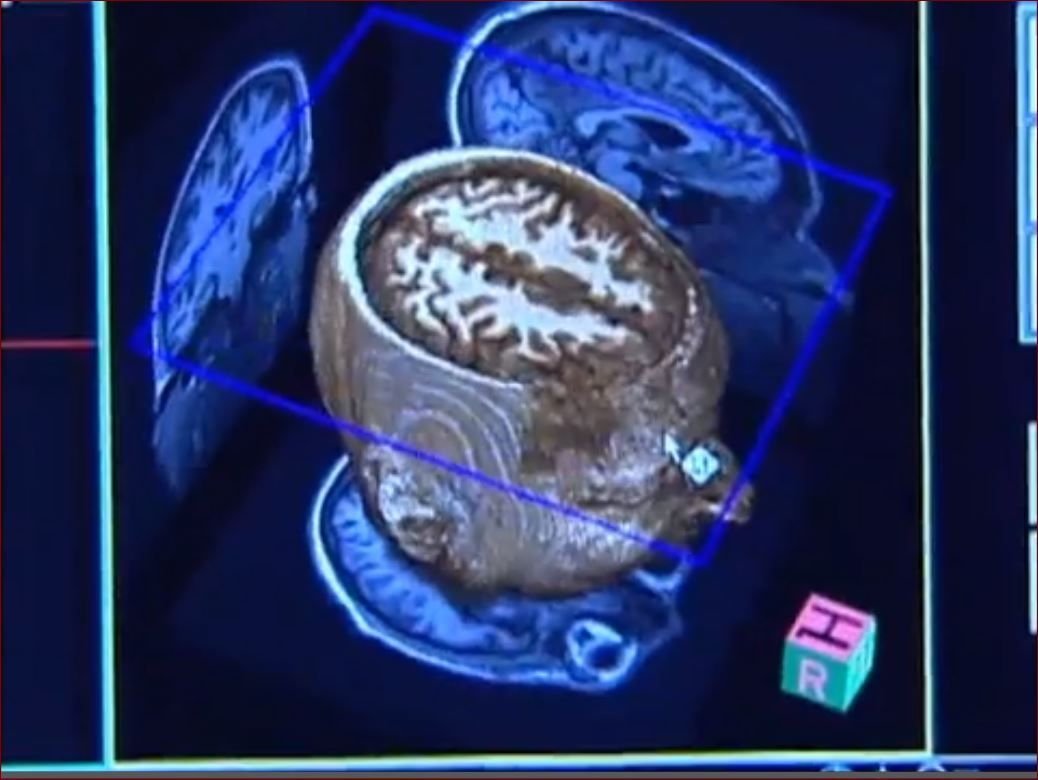

Human ‘mini brains’ grown in labs may help solve cancer, autism, Alzheimer’s

| Video Source: CNN

Read the full story CNN…

UPDATE: A generous contribution of $5,000 from the Methuselah Foundation has been received! This will put the fundraiser over the top of the cost and pay for the advanced Champions Oncology treatment described below.

However, Dr. Coles still has other medical expenses outstanding, and more will be coming in.

To cover these as well as Dr. Coles’s many other personal expenses, the fundraiser will now have an extended timeframe and the limit has been raised to $20,000.

We are currently at $13,385 of our 20,000 goal! Help us make it all the way!

Your contribution would help Dr. Coles continue his contributions and be greatly appreciated.

*** PLEASE alert your friends. L Stephen Coles spend his entire professional career trying to save your life; take a second to help save his.***

Methuselah Foundation

Offline Donation

donated $5,000.00

Friday, June 07, 2013

Anonymous

Offline Donation

donated $400.00

Friday, June 07, 2013

Chuck Wade

donated $20.00

Thursday, June 06, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

Tom Funk

donated $100.00

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

Gennady Stolyarov II

donated $50.00

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

Stephen Coles is one of the heroes of our time, who has contributed immensely to the prospects for longevity for all of us. I am honored to be able to assist him in his own struggle against a life-threatening illness, so that he could have decades and centuries more to fight the most dangerous, the most destructive enemies of senescence and death.Anonymous

Anonymous

donated $50.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

marshall zablen

donated $300.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Anonymous

donated $200.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Anonymous

donated $200.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Björn Kleinert

donated $50.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Get well !

Joao Pedro Magalhaes

donated $50.00

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Monday, June 03, 2013

Otto

donated $20.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

Anonymous

donated $20.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

Franco Cortese

donated $100.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

PLEASE donate ANYTHING you can to help save the life of L. Stephen Coles, who has spent his entire professional career trying to save yours!

Aubrey de Grey

donated $300.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

Anonymous

Offline Donation

donated$5,000.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

donated Hidden Amount

Monday, June 03, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Monday, June 03, 2013

Sven Bulterijs

donated $15.00

Monday, June 03, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Sunday, June 02, 2013

kg goldberger

donated $20.00

Sunday, June 02, 2013

prayers are on the way for more than 65% of deaths. Aging is a cause of adult cancer, stroke and many others age related diseases. Researchers fighting aging are the best people, they are fighting for all of us. Let’s pay them back!

Bijan Pourat MD

donated$250.00

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Maxim Kholin

donated Hidden Amount

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Aging is a disease. Aging is responsible

Anonymous

donated $60.00

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Nils Alexander Hizukuri

donated $30.00

Saturday, June 01, 2013

All the best!

Anonymous

donated $40.00

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Danny Bobrow

donated Hidden Amount

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Steve, win this fight for us all. I send you healing thoughts.

Danny

Steve, friends and family, but it is an outstanding, real-world example of the advancing frontier of science and medicine. The entire life-extension community should rally in support of this effort for Steve and for the acquisition of important scientific knowledge.

Cliff Hague

donated $100.00

Saturday, June 01, 2013

Best wishes for a speedy recovery.

Tom Coote

donated $100.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

With Best Wishes!

Anonymous

donated $100.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

Allen Taylor

donated$25.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

Gunther Kletetschka

donated Hidden Amount

Friday, May 31, 2013

john mccormack, Australia

donated $50.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

phil kernan

donated $100.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

Gary and Marie Livick

donated $100.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

ingeseim

donated Hidden Amount

Friday, May 31, 2013

TeloMe Inc.

donated $100.00

Friday, May 31, 2013

Not only is this an important cause for

-Preston Estep, Ph.D.

CEO and Chief Scientific Officer, TeloMe, Inc.

Not only is this an important cause for Steve, friends and family, but it is an outstanding, real-world example of the advancing frontier of science and medicine. The entire life-extension community should rally in support of this effort for Steve and for the acquisition of important scientific knowledge. –Preston Estep, Ph.D. CEO and Chief Scientific Officer, TeloMe, Inc.

Anonymous

donated $5.00

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Anonymous

donated $60.00

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Larry Abrams

donated $100.00

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Anonymous

donated Hidden Amount

Wednesday, May 29, 2013