Uniquely practical education, producing specialist clinical leaders and transforming local healthcare.

AI has emerged as a pivotal tool in redefining TBI rehabilitation, bridging gaps in traditional care with innovative, data-driven approaches. While its potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy, outcome prediction, and individualized therapy is evident, challenges such as bias in datasets and ethical implications must be addressed. Continued research and multidisciplinary collaboration will be key to harnessing AI’s full potential, ensuring equitable access and optimizing recovery outcomes for TBI patients.

Overall, the integration of AI in TBI rehabilitation presents numerous opportunities to advance patient care and enhance the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

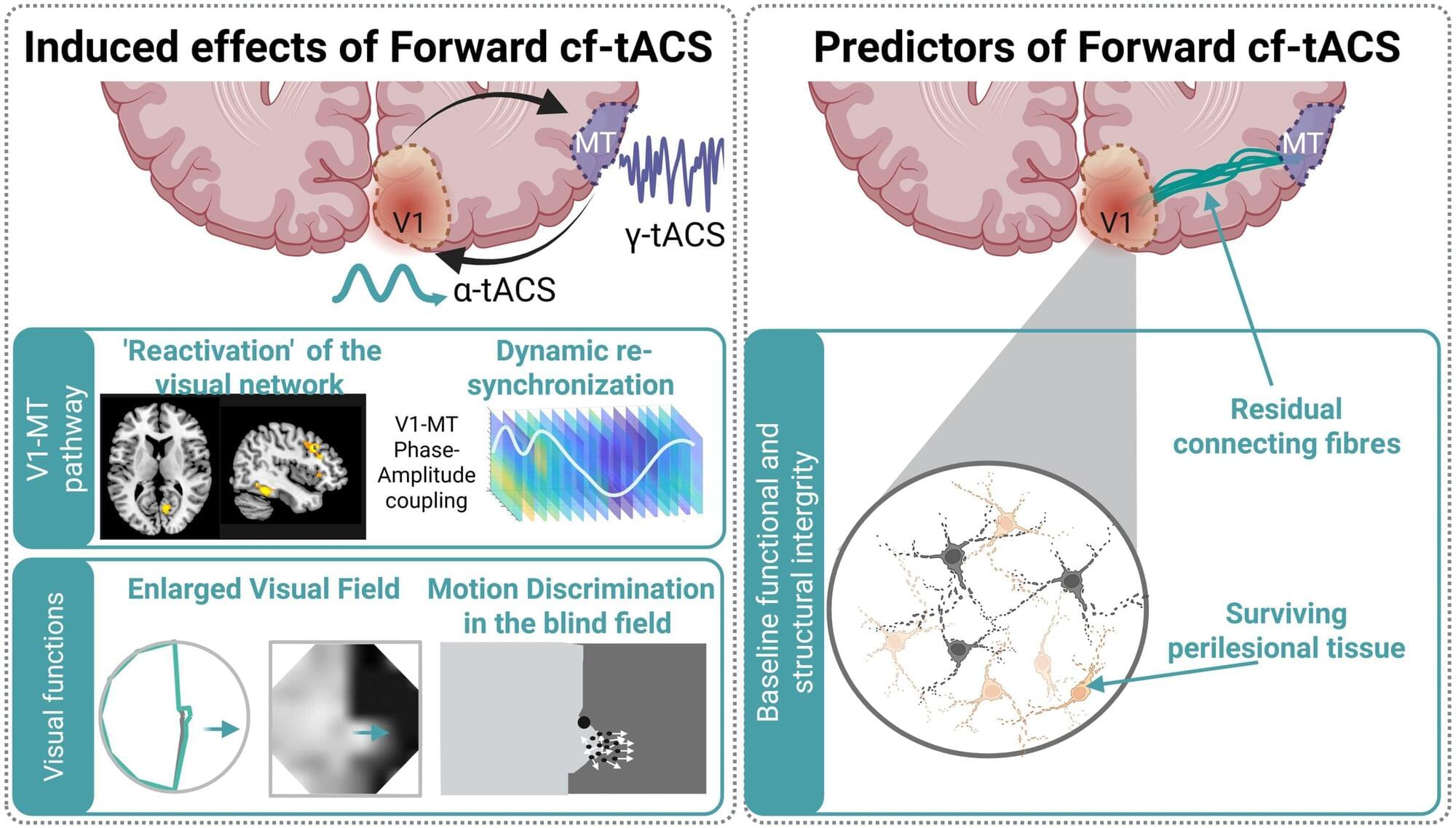

Scientists at EPFL have developed an innovative, non-invasive brain stimulation therapy to significantly improve visual function in stroke patients who have suffered vision loss following a stroke. The approach could offer a more efficient and faster way to regain visual function in such cases.

Each year, thousands of stroke survivors are left with hemianopia, a condition that causes loss of half of their visual field (the “vertical midline”). Hemianopia severely affects daily activities such as reading, driving, or just walking through a crowded space.

There are currently no treatments that can restore lost visual function in hemianopia satisfactorily. Most available options focus on teaching patients how to adapt to loss of vision rather than recovering it. To achieve some degree of recovery, months of intensive neurorehabilitative training are required for only moderate restoration at best.

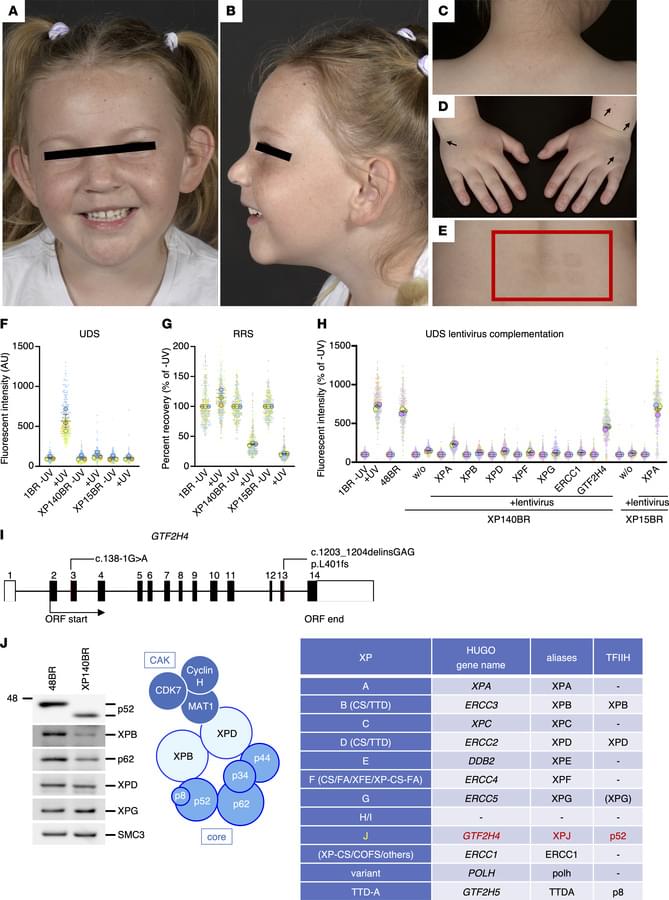

This issue’s cover features companion papers that exemplify how understanding a rare disease can inform treatment strategies in other conditions.

Fassihi et al. and Nakazawa et al. report on the C-terminal deletion of transcription factor TFIIH-p52 subunit as a cause of xeroderma pigmentosum.

The cover art was created using PyMOL; TFIIH-p52 subunit (blue; C-terminus in white). Image credit: Keiko Itano.

https://www.jci.org/articles/view/195731 https://www.jci.org/articles/view/195732

1National Xeroderma Pigmentosum Service, Rare Disease Centre, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom.

2Department of Molecular Genetics, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan.

Electrons can freeze into strange geometric crystals and then melt back into liquid-like motion under the right quantum conditions. Researchers identified how to tune these transitions and even discovered a bizarre “pinball” state where some electrons stay locked in place while others dart around freely. Their simulations help explain how these phases form and how they might be harnessed for advanced quantum technologies.

A San Diego biotech has set out to solve the formula for best-in-class antibody-drug conjugates, raising $120 million with support from Big Pharma Merck & Co. to fuel its efforts.

Solve Therapeutics’ new fundraise was led by oncology-focused VC Yosemite, with participation from new investors Abingworth and Merck, plus existing investors Alexandria Venture Investments and Citadel’s Surveyor Capital, among others.

SpaceKids Global; Inspiring students to excel in STEAM+ Environment education; with a focus on empowering young girls.