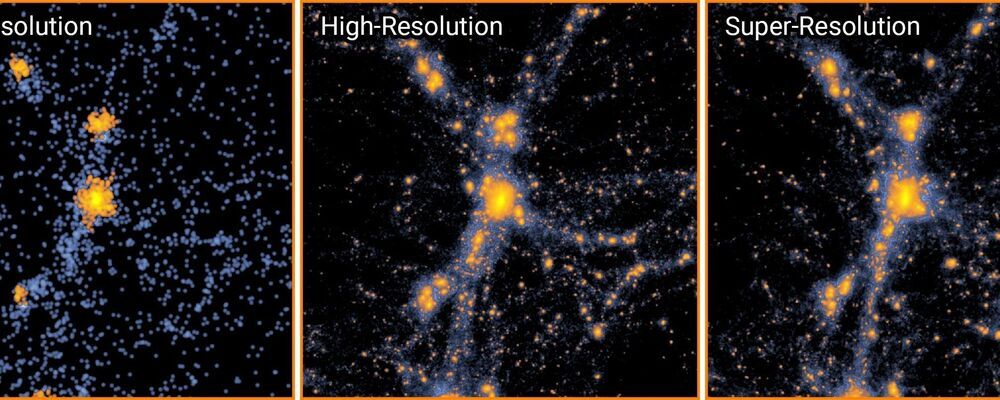

Using neural networks, Flatiron Institute research fellow Yin Li and his colleagues simulated vast, complex universes in a fraction of the time it takes with conventional methods.

Using a bit of machine learning magic, astrophysicists can now simulate vast, complex universes in a thousandth of the time it takes with conventional methods. The new approach will help usher in a new era in high-resolution cosmological simulations, its creators report in a study published online on May 4, 2021, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“At the moment, constraints on computation time usually mean we cannot simulate the universe at both high resolution and large volume,” says study lead author Yin Li, an astrophysicist at the Flatiron Institute in New York City. “With our new technique, it’s possible to have both efficiently. In the future, these AI-based methods will become the norm for certain applications.”