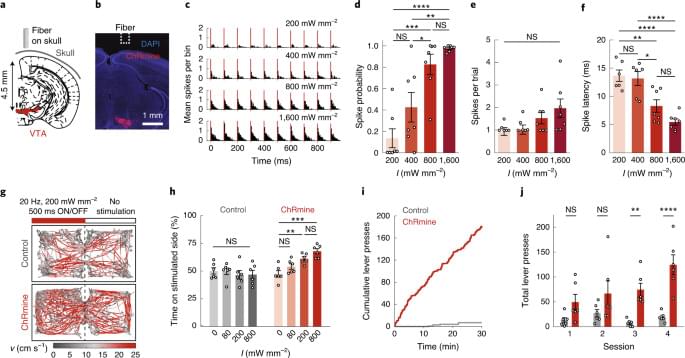

Optogenetic control of neural activity in the deep brain is achieved without intracranial surgery using ChRmine.

Ben Goertzel in response to some common objections covered in an article on io9 by George Dvorsky ‘You’ll Probably Never Upload Your Mind Into A Computer’: http://io9.com/you-ll-probably-never-upload-your-mind-into-a-computer-474941498

Objections are covered in order as they appear in the article:

1. Brain functions are not computable.

2. We’ll never solve the hard problem of consciousness.

3. We’ll never solve the binding problem.

4. Panpsychism is true.

5. Mind-body dualism is true.

6. It would be unethical to develop.

7. We can never be sure it works.

8. Uploaded minds would be vulnerable to hacking and abuse.

Ben Goertzel wrote a response to the io9 article: http://hplusmagazine.com/2013/04/20/goertzel-contra-dvorsky-on-mind-uploading/

Dust is a common fact of life, and it’s more than just a daily nuisance—it can get into machinery and equipment, causing loss of efficiency or breakdowns.

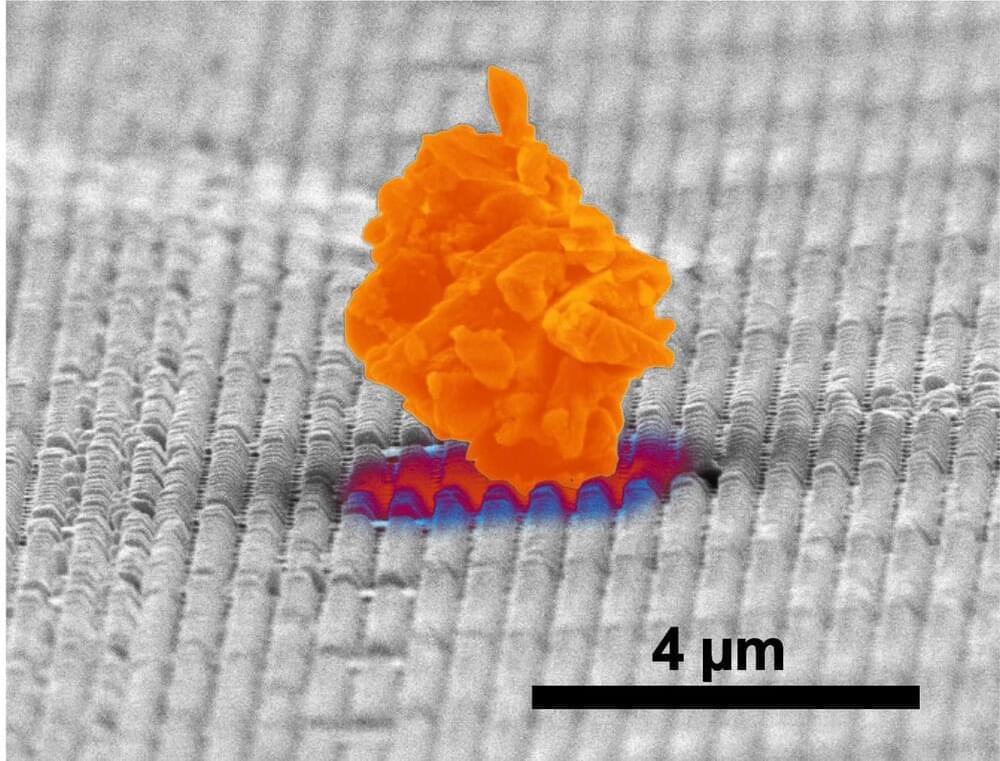

Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin partnered with North Carolina-based company Smart Material Solutions Inc. to develop a new method to keep dust from sticking to surfaces. The result is the ability to make many types of materials dust resistant, from spacecraft to solar panels to household windows.

The research is published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Synthetic speech and voice cloning startup Resemble AI has introduced an “audio watermark” to tag AI-generated speech without compromising sound quality. The new PerTh Perceptual Threshold) Watermarker embeds the sonic signature of Resemble’s synthetic media engine into a recording to mark its AI origin regardless of future audio manipulation, yet subtle enough that no human can hear it.

Audio Watermarking

Visual watermarking hides one image within another, invisible without a computer scanner in the case of particularly high-security documents. The same principle applies to audio watermarks, except it’s a very soft sound that people won’t notice but encoded with information that a computer could decipher. The concept isn’t new, but Resemble has leveraged its audio AI to make PerTh more reliable without compromising the realism of its synthetic speech creation.

Quiet sounds can be obliterated easily in most cases, but Resemble figured out a way to hide its identification tones within the sounds of speech. As people talking is the point of Resemble’s services, the audio watermark is much more likely to come through an edit unscathed. Resemble takes advantage of how humans tend to focus on specific frequencies and how louder sounds can hide quieter noises that are close in frequency. The combination masks and protects the watermark sound from humans noticing or being able to extract the audio watermark. Resemble’s machine learning model can determine where to embed the quiet sonic tag, generate the appropriate sound, and put it in place. The diagram below illustrates how the watermark hides in plain sight, or sound in this case.

Blurring lines between man and machine.

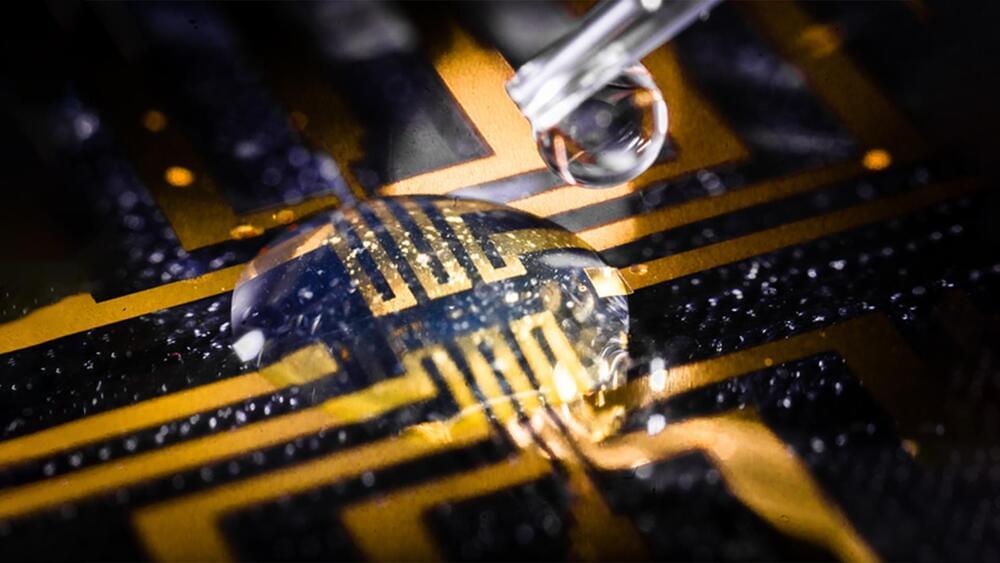

A breakthrough has made way for a new paradigm in bioelectronics. Earlier, it took the implantation of physical objects to initiate electronic processes in the body. Humans have incorporated technology to enhance the human experience and take charge of their evolution. They’ve also integrated devices within them that could alternately function as organs when biological tissues fail.

Scientists have now developed a viscous gel that will be enough in the future.

Researchers at Linköping, Lund, and Gothenburg universities in Sweden have successfully grown electrodes in living tissue using the body’s molecules as triggers.

Thor Balkhed.

Earlier, it took the implantation of physical objects to initiate electronic processes in the body. Humans have incorporated technology to enhance the human experience and take charge of their evolution. They’ve also integrated devices within them that could alternately function as organs when biological tissues fail.

The brain signals successfully directed the robodogs toward a number of locations that the human controller picked “telepathically” by imagining them.

The Australian military is reportedly testing a unique artificial intelligence (AI) “brain robotic interface” to control “robodogs” synced with troopers’ minds.

The army “is exploring the use of brain signals to control robotic and autonomous systems.” reads the video description.

Australian Army.

The breakthrough AI allows soldiers to control these robot dogs or ‘robodogs’ using advanced digital “telepathy,” according to a video released by the Australian army last week.

Firstly, the space agency must develop a battery that can withstand Venus’ hellish conditions.

You may be surprised to learn that humans have sent several landers to Venus’ surface. The Soviet Venera missions, for example, transmitted the first-ever image from another planet on October 20, 1975, after sending its Venera 9 lander to the surface of Venus.

That mission lasted less than two hours on the planet’s surface due to the immense atmospheric pressure and scorching temperatures on Earth’s so-called evil twin.

Now, NASA aims to build a lander called LLISSE, that can withstand those conditions and beam a wealth of data about our nearest planetary neighbor back to Earth.

Lunar and Planetary Institute.

The Soviet Venera missions, for example, transmitted the first-ever image from another planet on October 20, 1975, after sending its Venera 9 lander to the surface of Venus.