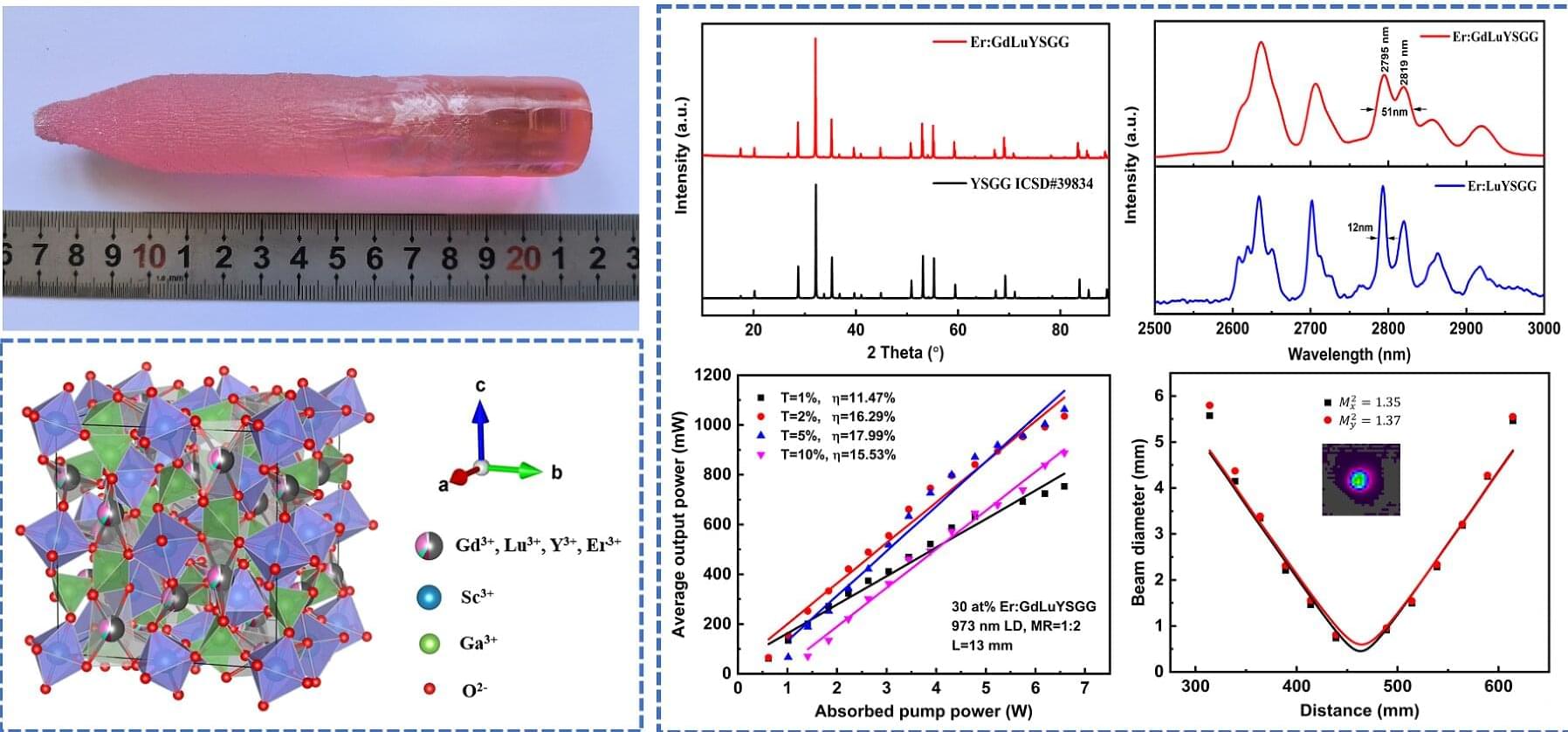

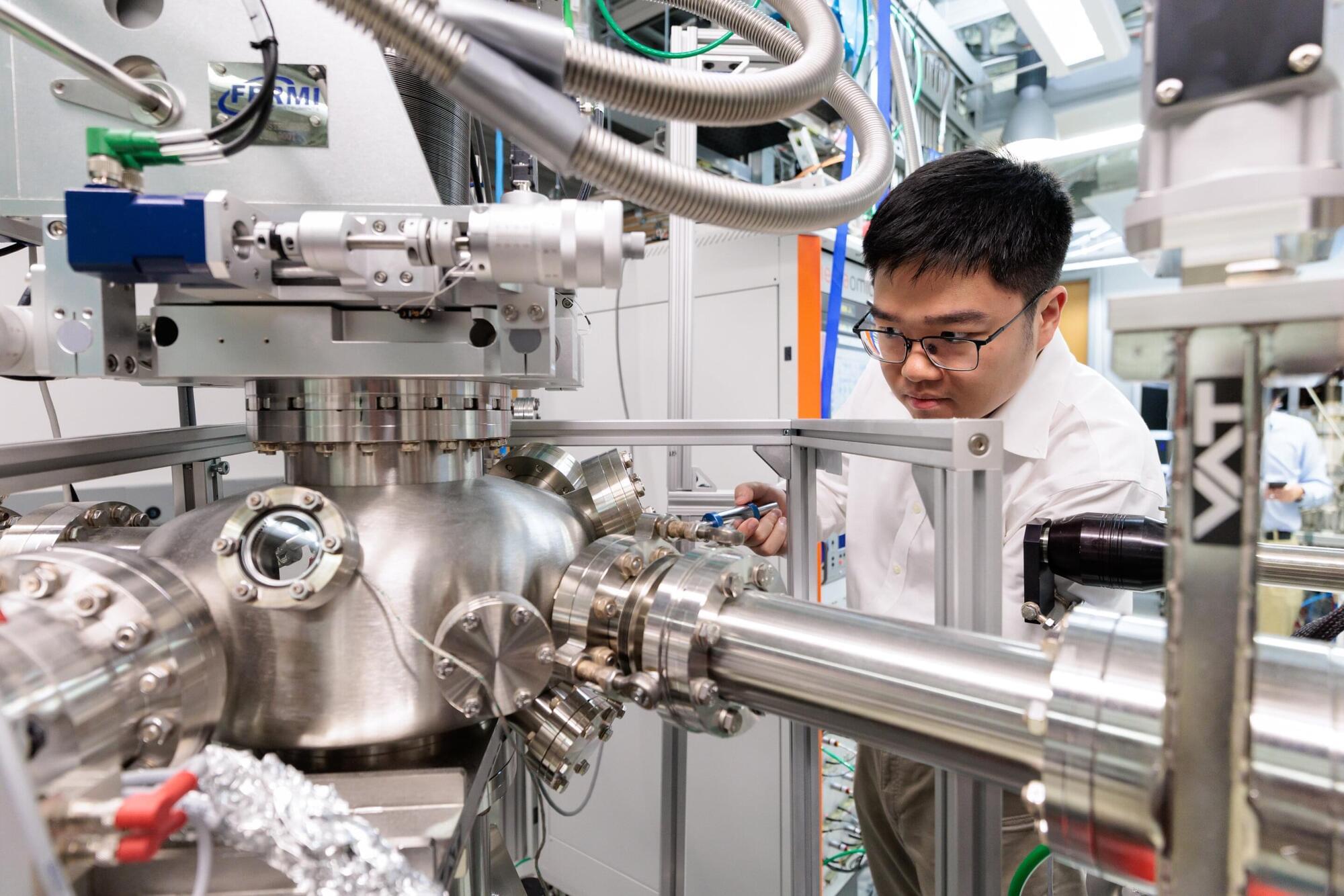

A research team from the Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics (XIOPM) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with collaborators from the Institute National de la Recherche Scientifique, Canada, and Northwest University, has developed a single-shot compressed upconversion photoluminescence lifetime imaging (sCUPLI) system for high-speed imaging.

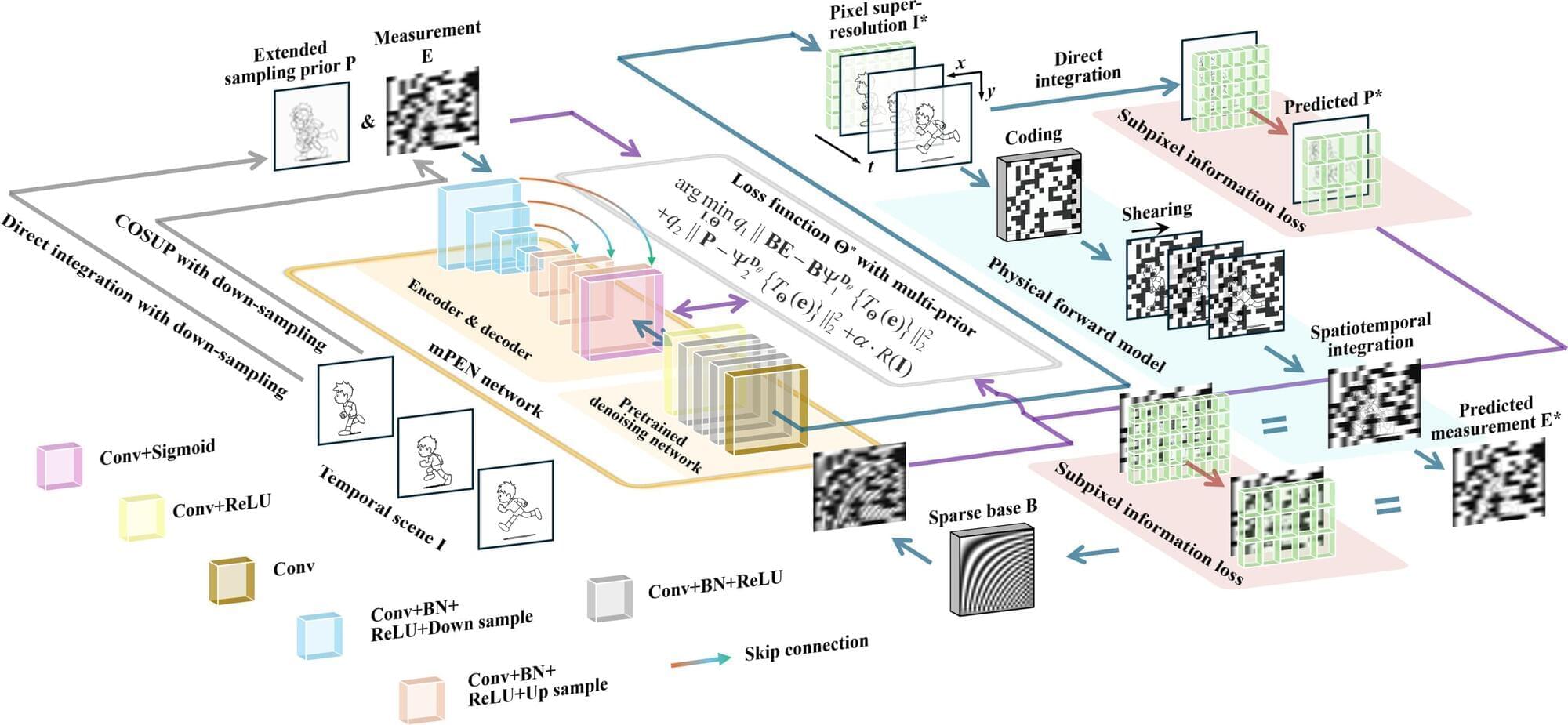

High-fidelity recovery from complex inverse problems remains a key challenge in compressed high-speed imaging. Deep learning has revolutionized the reconstruction, but pure end-to-end “black-box” networks often suffer from structural artifacts and high costs. To address these issues, the team from XIOPM propose a multi-prior physics-enhanced neural network (mPEN) in an article published in Ultrafast Science.

By integrating mPEN with compressed optical streak ultra-high-speed photography (COSUP), the researchers developed the sCUPLI system. This system utilized an encoding path for temporal shearing and a prior path to record unencoded integral images. It effectively suppressed artifacts and corrected spatial distortion by synergistically correcting multiple complementary priors including physical models, sparsity constraints, and deep image priors.