How is ventilation at various depth layers of the Atlantic connected and what role do changes in ocean circulation play? Researchers from Bremen, Kiel and Edinburgh have pursued this question and their findings have now been published in Nature Communications.

Salt water in the oceans is not the same everywhere; there are water layers that have different salinities and temperatures. The phenomenon of thermohaline circulation—which results from the differences in density caused by variations in temperature and salinity—drives the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), among other current patterns. Near the surface, however, ocean circulation is also influenced by winds, which are responsible for producing the large subtropical gyres in the Atlantic, both on the northern and southern sides of the equator.

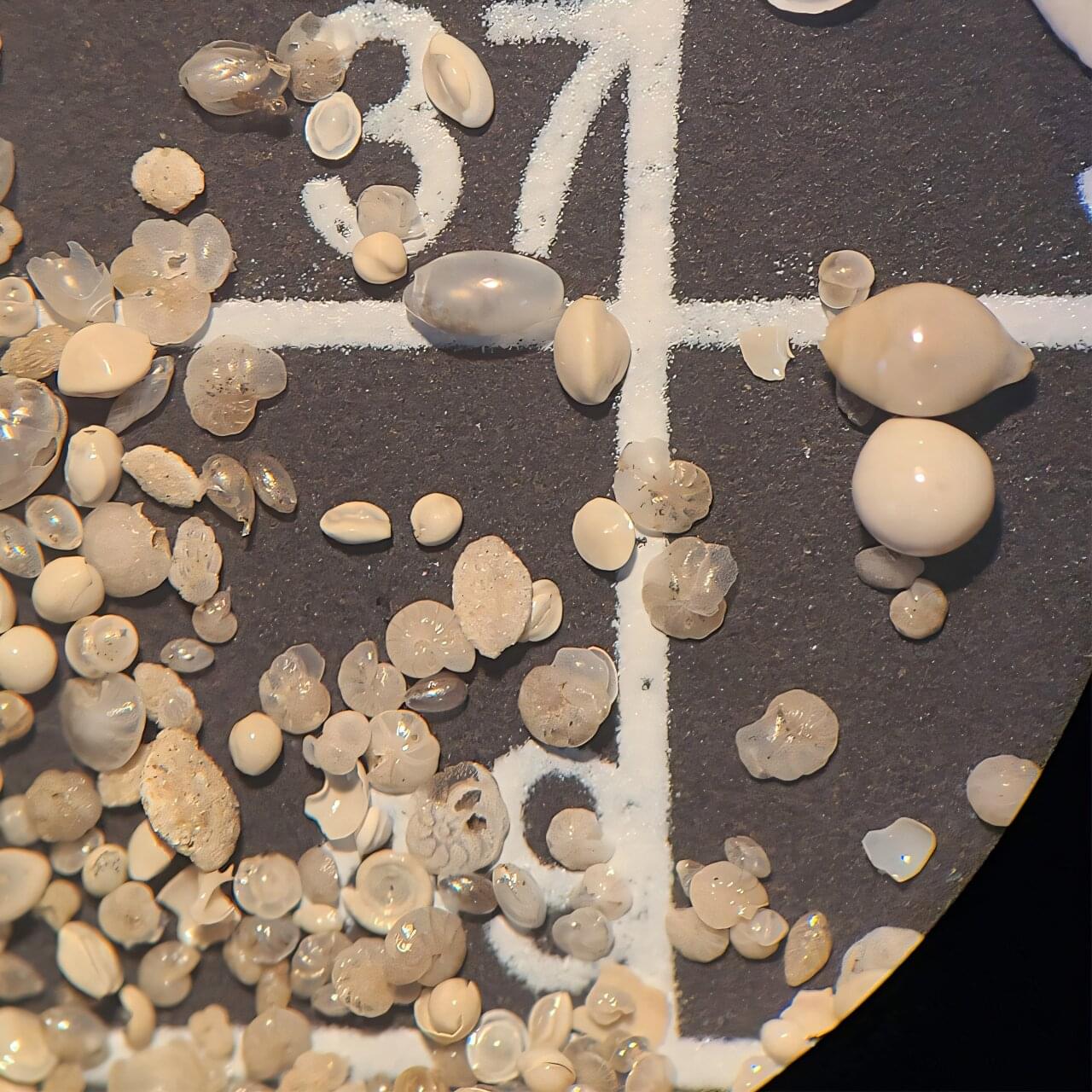

These gyres play an important role in marine ecosystems because they provide organisms on the sea floor with oxygen, which is then consumed in part by the decomposition of organic matter. If there is a paucity of fresh, cold, and oxygen-rich water transported in to ventilate these areas, so to speak, oxygen minimum zones result.