One of the largest mysteries of science is that humans have conscious awareness of their complex subjective experiences – or what we call “qualia” – such as being aware of what it’s like to delight in the color of a flower, melt into the comfort of a bed, or to feel sharp pain. Why and how qualia could emerge from physical matter and be a part of the human experience is unknown, and this is called the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. Related to qualia is the mystery of why humans feel like they have free will, or the ability to intentionally choose and execute actions.

The ‘easy’ problem of consciousness is mapping these mind states to brain states, such as identifying which brain regions are active during a certain experience, such as smelling a flower. Despite advances in classical physics and neuroscience, many aspects of the mind-brain relationship, such as qualia, remain unresolved. New theories of mind are required to address this perennial mystery.

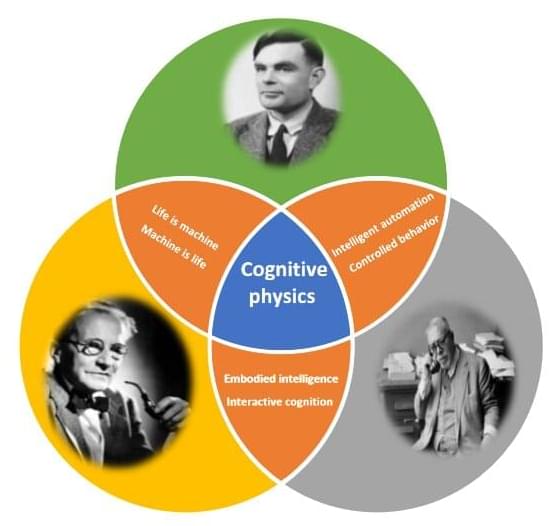

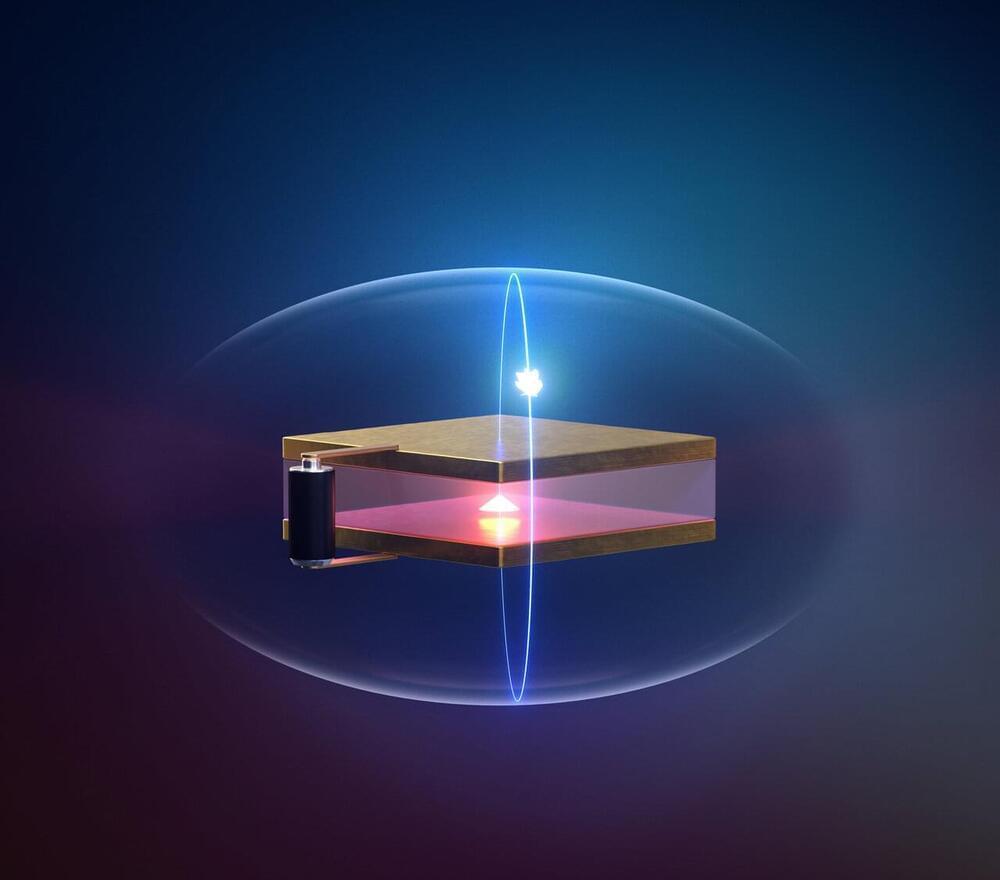

In a new paper, we propose that some aspects of mind are quantum and can play an active role in the physical world, explaining some of the unexplainable.