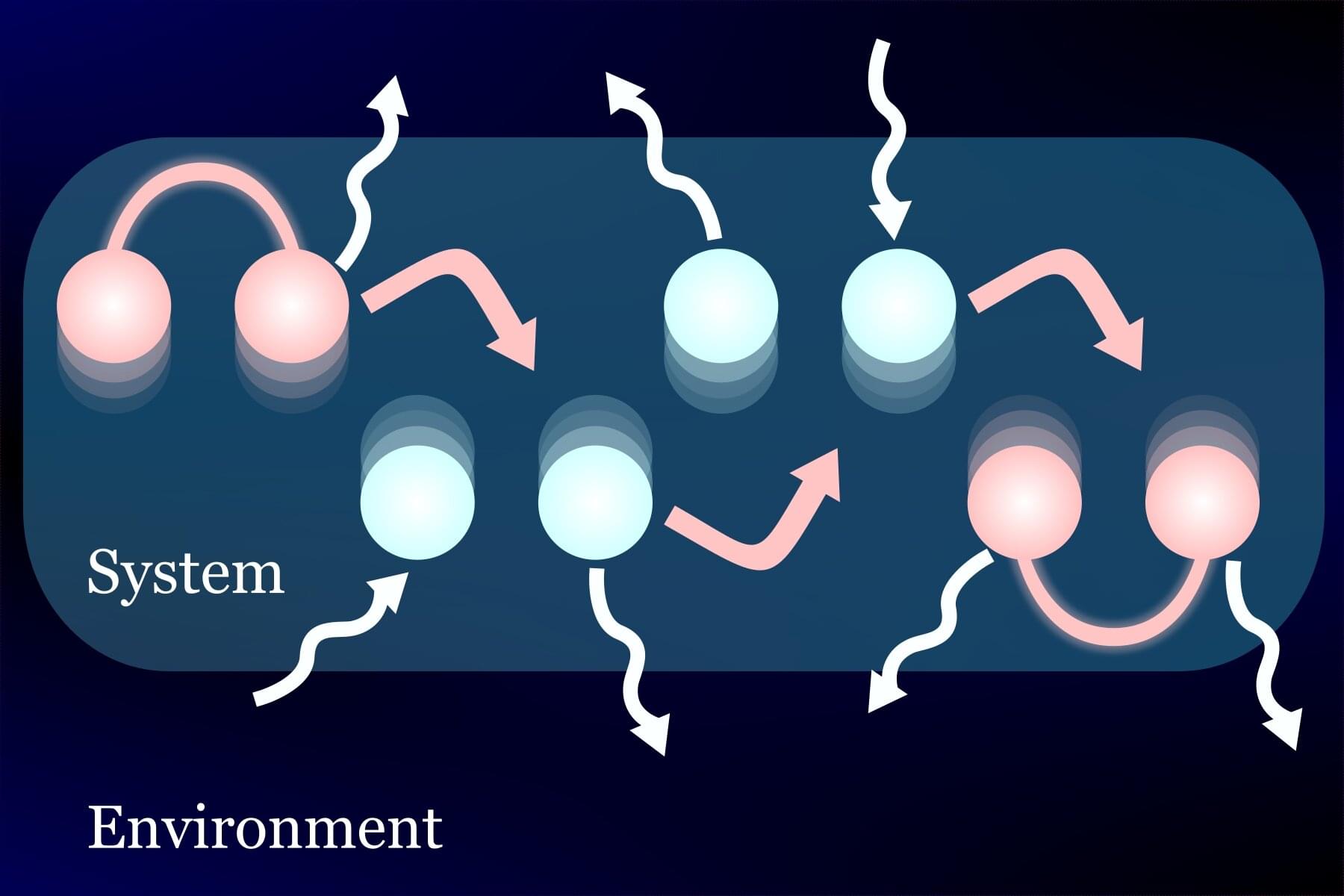

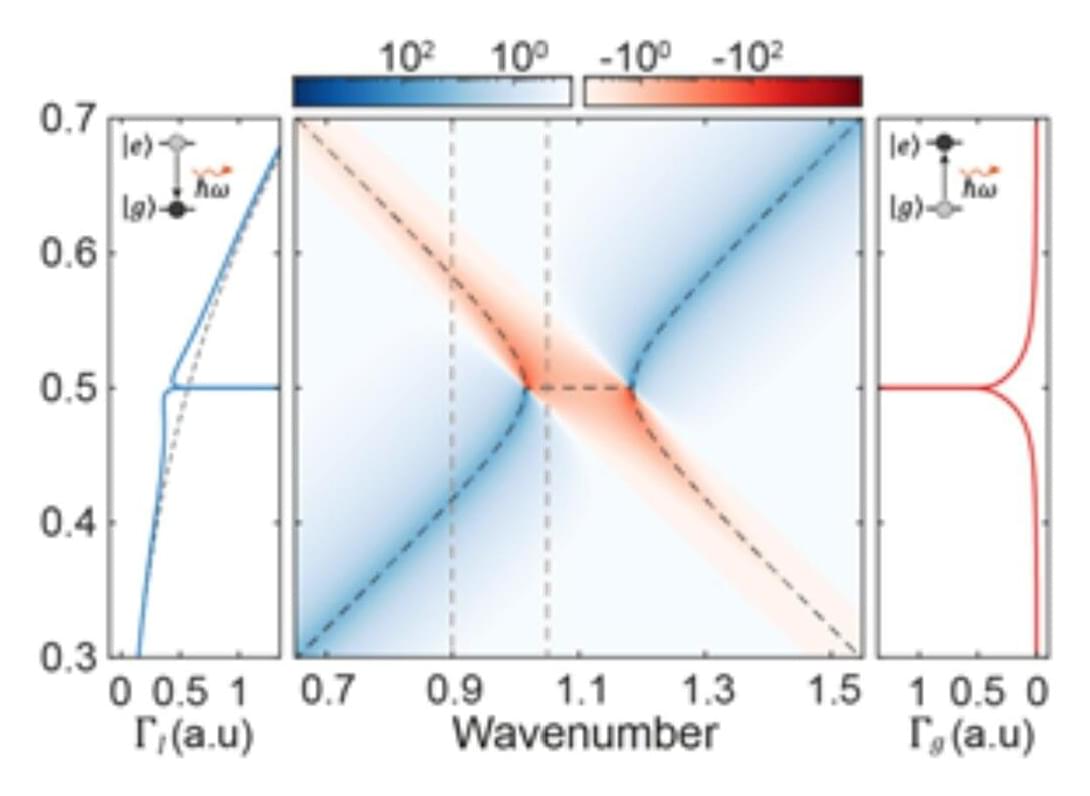

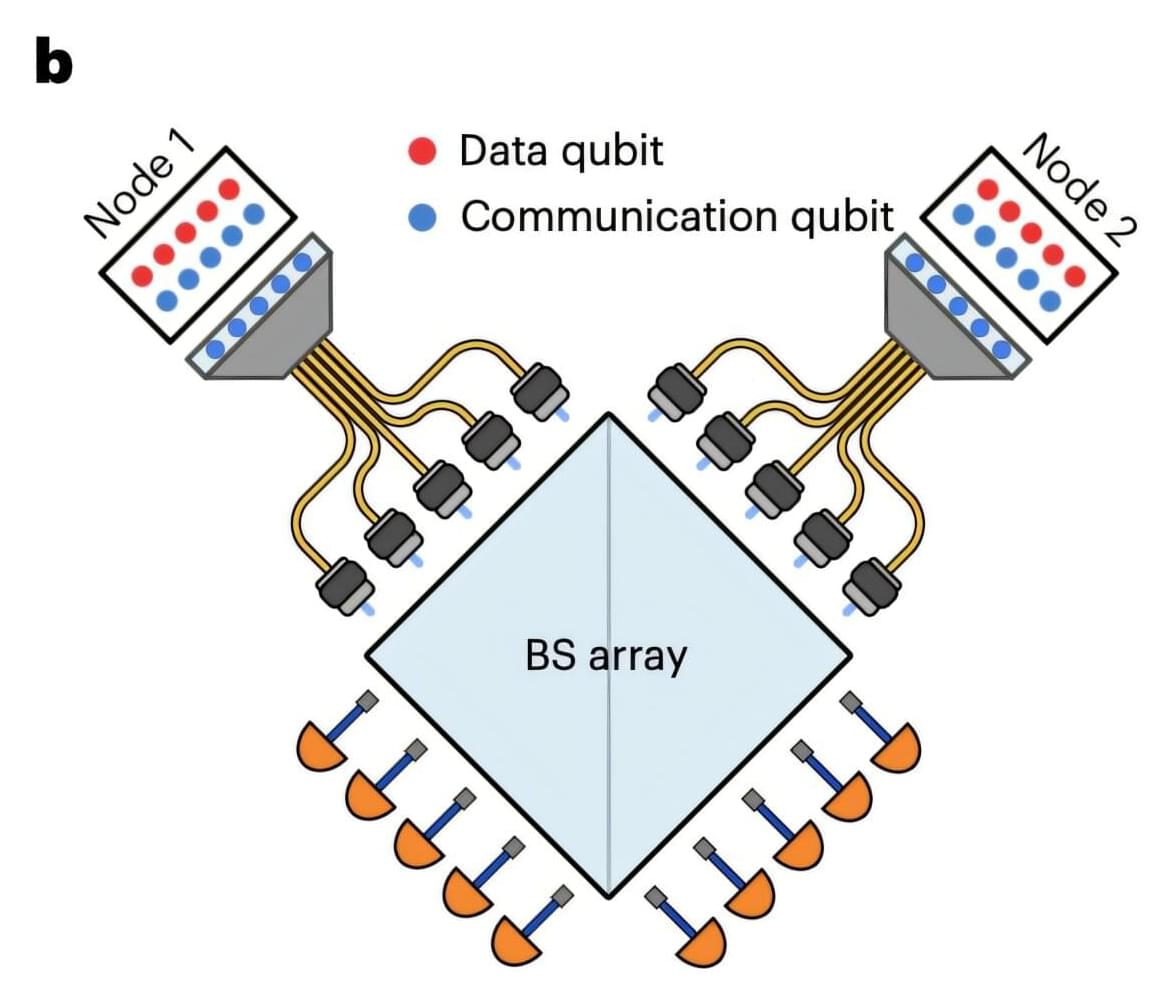

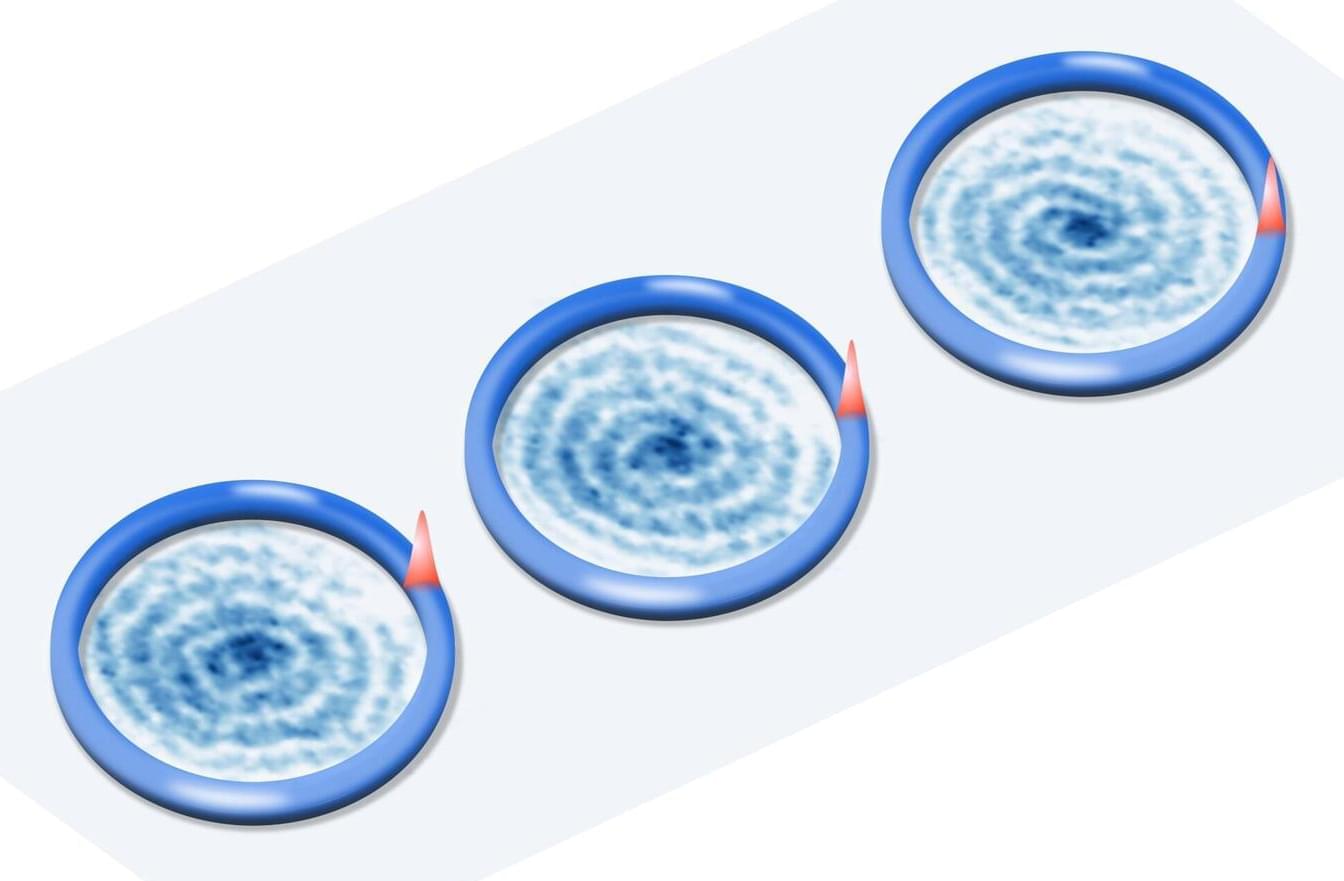

A study from Rice University, published in PRX Quantum, has found that energy transfers more quickly between molecular sites when it starts in an entangled, delocalized quantum state instead of from a single site. The discovery could lead to the development of more efficient light-harvesting materials that enhance the conversion of energy from light into other forms of energy.

Many biochemical processes, including photosynthesis, depend on rapid and efficient energy transfer following absorption. Understanding how quantum mechanical effects like entanglement influence these processes at room temperature could significantly change our approach to creating artificial systems that mimic nature’s efficiency.

“Delocalizing the initial excitation across multiple sites accelerates the transfer in ways that starting from a single site cannot achieve,” said Guido Pagano, the study’s corresponding author and assistant professor of physics and astronomy.