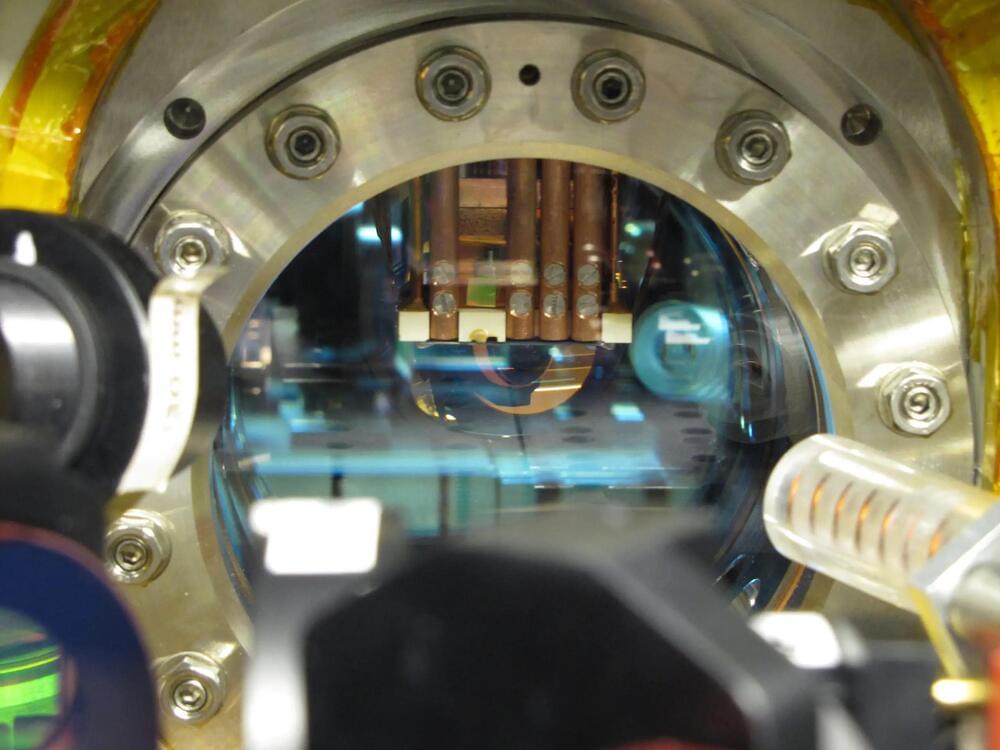

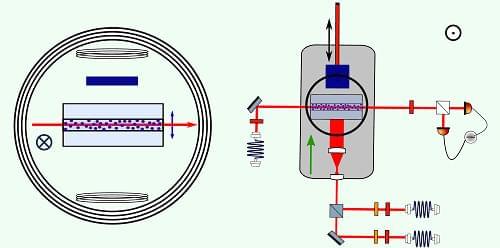

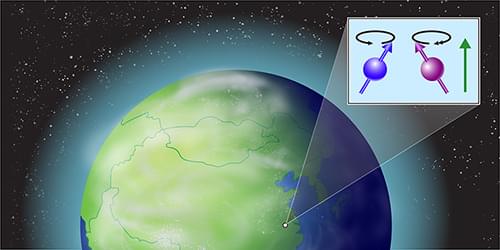

In my work, I build instruments to study and control the quantum properties of small things like electrons. In the same way that electrons have mass and charge, they also have a quantum property called spin. Spin defines how the electrons interact with a magnetic field, in the same way that charge defines how electrons interact with an electric field. The quantum experiments I have been building since graduate school, and now in my own lab, aim to apply tailored magnetic fields to change the spins of particular electrons.

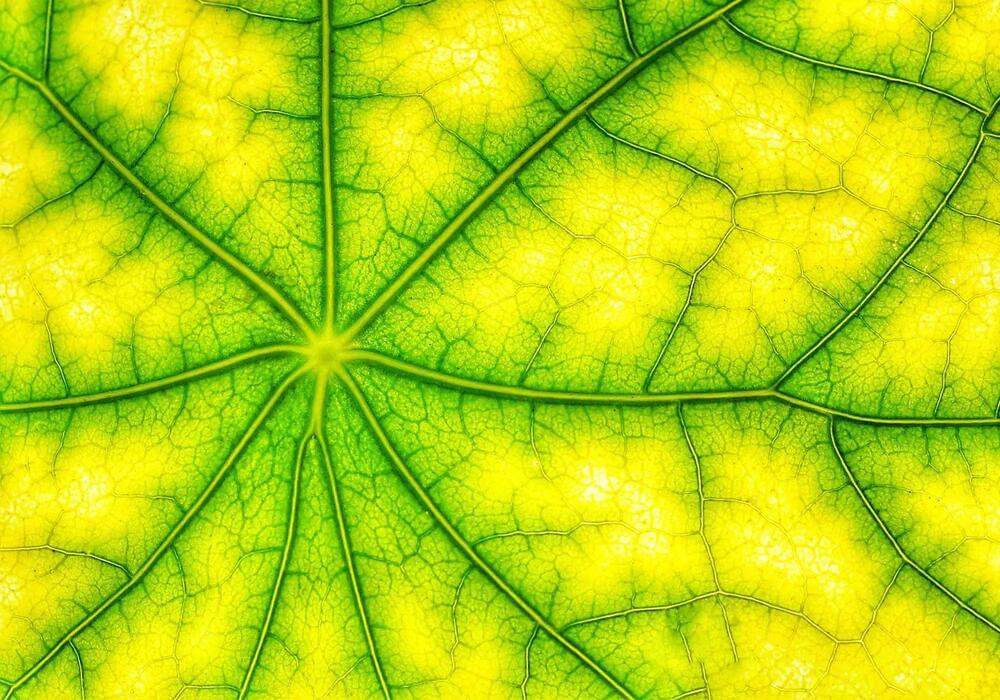

Research has demonstrated that many physiological processes are influenced by weak magnetic fields. These processes include stem cell development and maturation, cell proliferation rates, genetic material repair, and countless others. These physiological responses to magnetic fields are consistent with chemical reactions that depend on the spin of particular electrons within molecules. Applying a weak magnetic field to change electron spins can thus effectively control a chemical reaction’s final products, with important physiological consequences.

Currently, a lack of understanding of how such processes work at the nanoscale level prevents researchers from determining exactly what strength and frequency of magnetic fields cause specific chemical reactions in cells. Current cell phone, wearable, and miniaturization technologies are already sufficient to produce tailored, weak magnetic fields that change physiology, both for good and for bad. The missing piece of the puzzle is, hence, a “deterministic codebook” of how to map quantum causes to physiological outcomes.