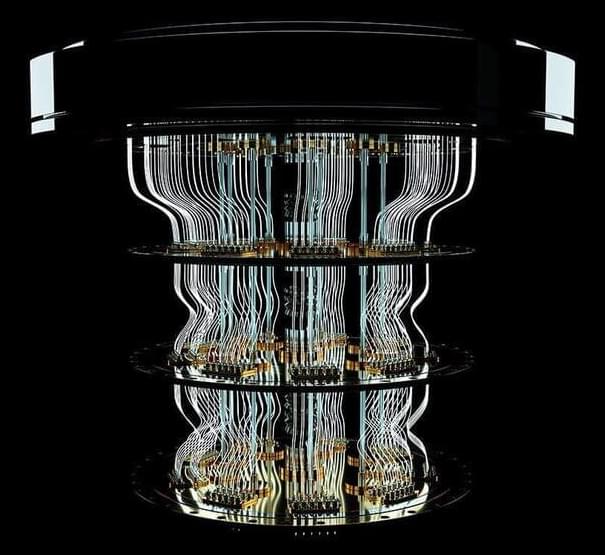

A fluxonium qubit can keep its most useful quantum properties for about 1.48 milliseconds, drastically longer than similar qubits currently favoured by the quantum computing industry.

A fluxonium qubit can keep its most useful quantum properties for about 1.48 milliseconds, drastically longer than similar qubits currently favoured by the quantum computing industry.

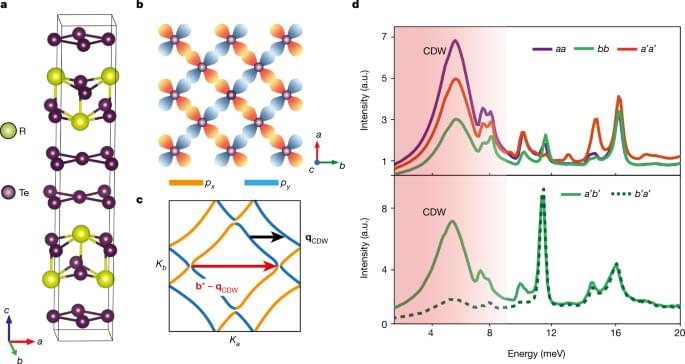

Scientists at EPFL have found a new way to create a crystalline structure called a “density wave” in an atomic gas. The findings can help us better understand the behavior of quantum matter, one of the most complex problems in physics. The research was published May 24 in Nature.

“Cold atomic gases were well known in the past for the ability to ‘program’ the interactions between atoms,” says Professor Jean-Philippe Brantut at EPFL. “Our experiment doubles this ability.” Working with the group of Professor Helmut Ritsch at the University of Innsbruck, they have made a breakthrough that can impact not only quantum research but quantum-based technologies in the future.

Scientists have long been interested in understanding how materials self-organize into complex structures, such as crystals. In the often-arcane world of quantum physics, this sort of self-organization of particles is seen in “density waves,” where particles arrange themselves into a regular, repeating pattern or order; like a group of people with different colored shirts on standing in a line but in a pattern where no two people with the same color shirt stand next to each other.

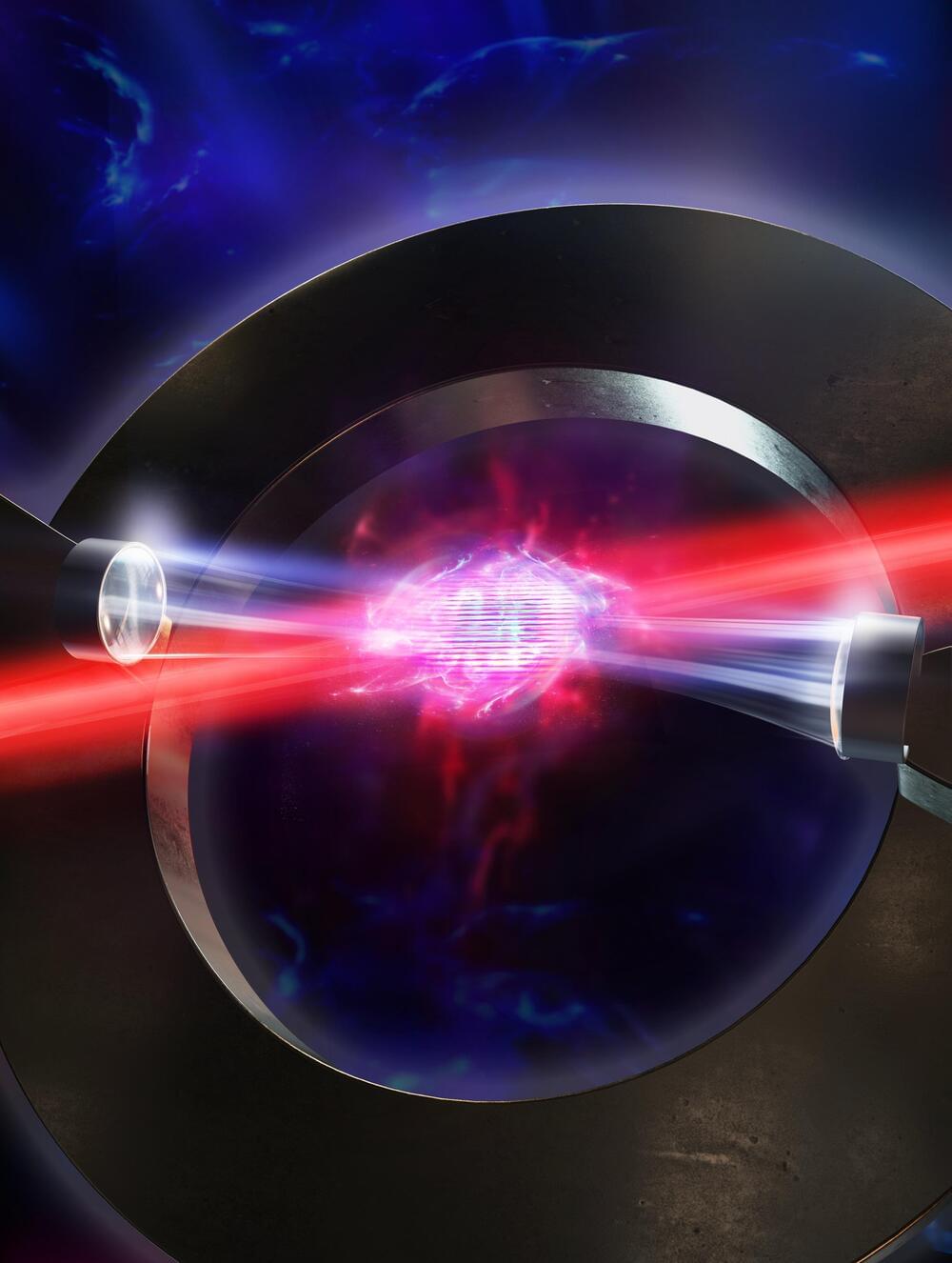

A quantum repeater based on trapped ions allows the transmission of entangled, telecom-wavelength photons over 50 km.

Communication networks have transformed our society over the past half century, and we can scarcely imagine our daily lives without them. Recent advances in the emergent field of quantum technologies have exhilarated scientists about the possibility of linking quantum devices in networks. Long-distance quantum communication portends functionality that is beyond the reach of classical networks [1]. To make full use of entanglement and other quantum effects, quantum networks exchange signals at the level of single photons. As a result, attenuation in fiber is the dominant source of error in these systems. Photon loss, however, can be remedied using a set of intermediate network nodes, called quantum repeaters, which create a direct entangled connection between distant network nodes [2].

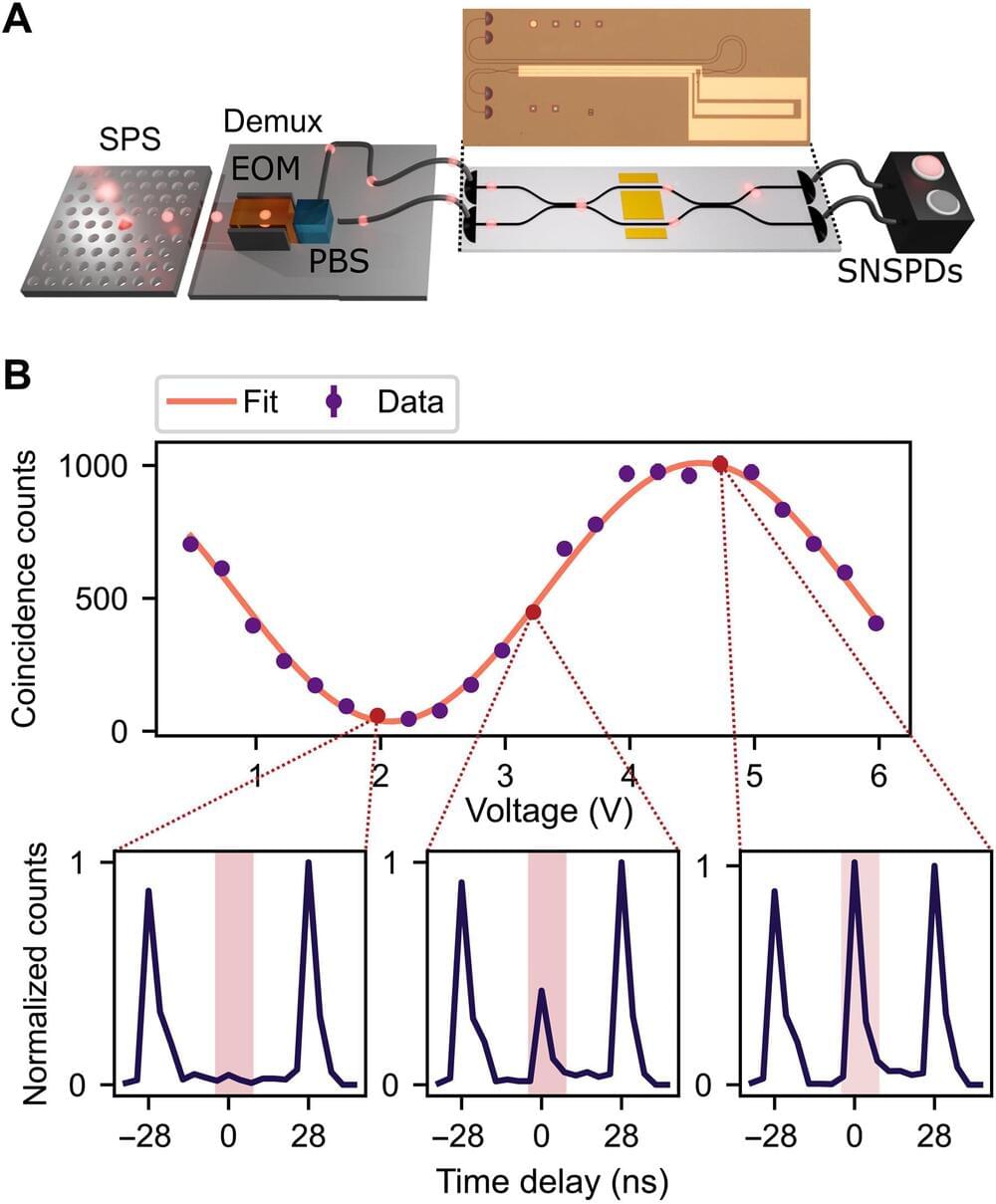

Scalable photonic quantum computing architectures require photonic processing devices. Such platforms rely on low-loss, high-speed, reconfigurable circuits and near-deterministic resource state generators. In a new report now published in Science Advances, Patrik Sund and a research team at the center of hybrid quantum networks at the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Münster developed an integrated photonic platform with thin-film lithium niobate. The scientists integrated the platform with deterministic solid-state single photon sources using quantum dots in nanophotonic waveguides.

They processed the generated photons within low-loss circuits at speeds of several gigahertz and experimentally realized a variety of key photonic quantum information processing functionalities on high-speed circuits; with inherent key features to develop a four-mode universal photonic circuit. The results illustrate a promising direction in the development of scalable quantum technologies by merging integrated photonics with solid-state deterministic photon sources.

Quantum technologies have progressively advanced in the past several years to enable quantum hardware to compete with and surpass the capabilities of classical supercomputers. However, it is challenging to regulate quantum systems at scale for a variety of practical applications and also to form fault-tolerant quantum technologies.

A quarter century ago, theoretical physicists at the University of Innsbruck made the first proposal on how to transmit quantum information via quantum repeaters over long distances, which would open the door to the construction of a worldwide quantum information network.

Now, a new generation of Innsbruck researchers has built a quantum repeater node for the standard wavelength of telecommunication networks and transmitted quantum information over tens of kilometers. The study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Quantum networks connect quantum processors or quantum sensors with each other. This allows tap-proof communication and high-performance distributed sensor networks. Between network nodes, quantum information is exchanged by photons that travel through optical waveguides. Over long distances, however, the likelihood of photons being lost increases dramatically.

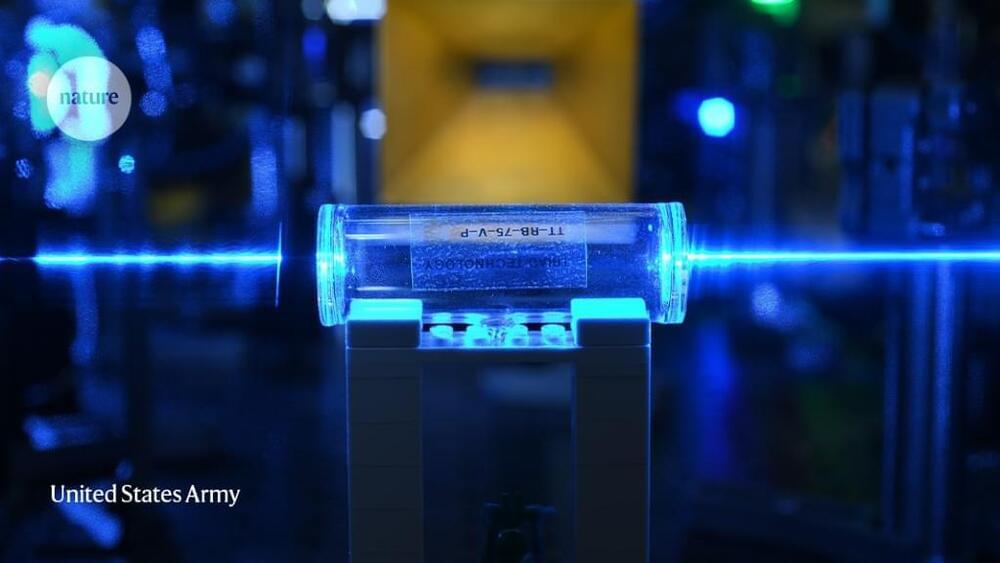

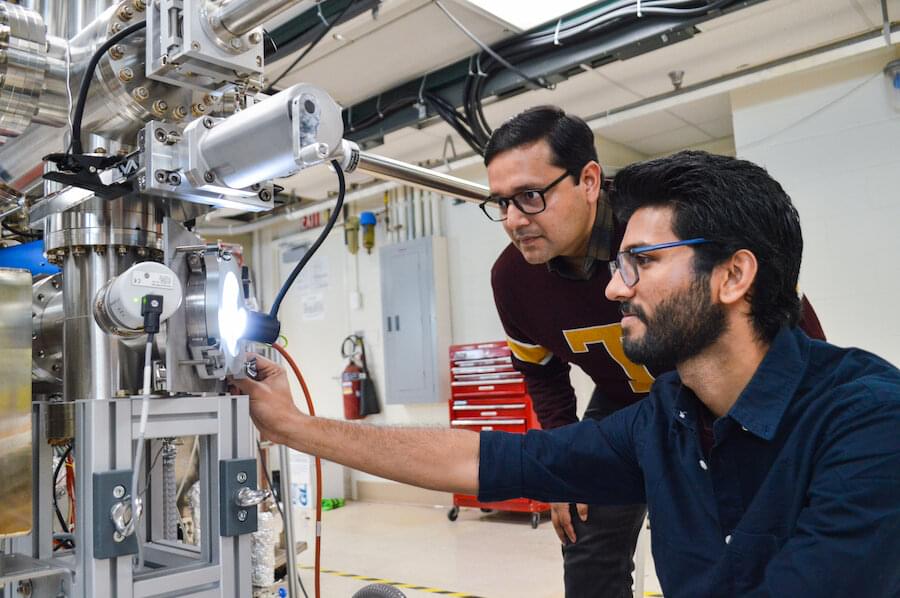

A University of Minnesota Twin Cities-led team has developed a first-of-its-kind, breakthrough method that makes it easier to create high-quality metal oxide thin films out of “stubborn” metals that have historically been difficult to synthesize in an atomically precise manner. This research paves the way for scientists to develop better materials for various next-generation applications including quantum computing, microelectronics, sensors, and energy catalysis.

The researchers’ paper is published in Nature Nanotechnology.

“This is truly remarkable discovery, as it unveils an unparalleled and simple way for navigating material synthesis at the atomic scale by harnessing the power of epitaxial strain,” said Bharat Jalan, senior author on the paper and a professor and Shell Chair in the University of Minnesota Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science.

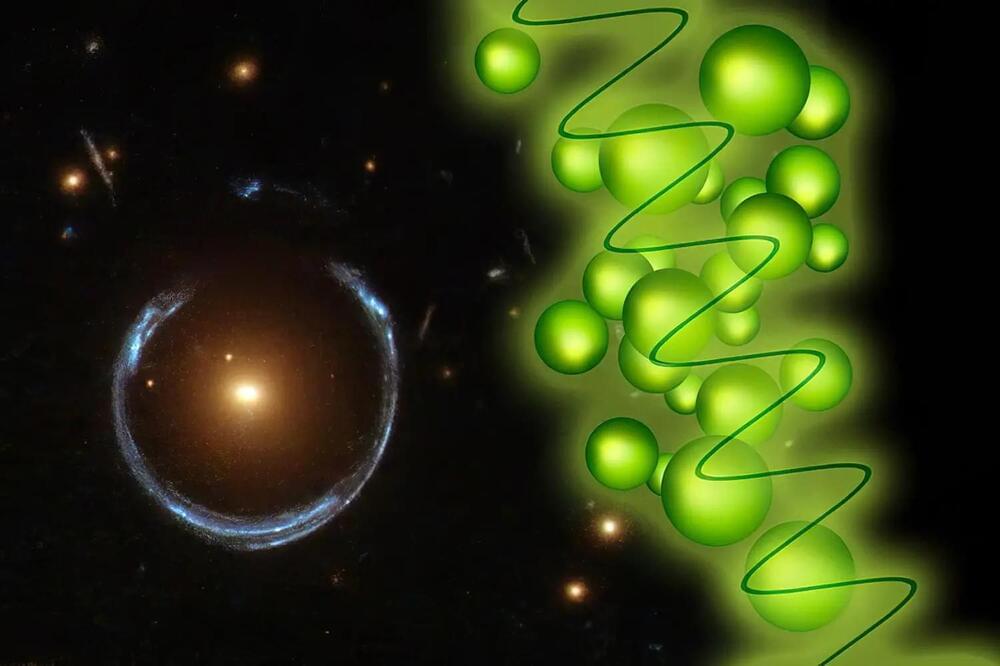

New techniques can answer questions that were previously inaccessible experimentally — including questions about the relationship between quantum mechanics and relativity.

Scientists at TU Wien and other institutions have developed a “quantum simulator” using ultracold atomic clouds to model quantum particles in curved spacetime, marking a major step toward reconciling quantum theory and the theory of relativity. The model system offers a tool to study gravitational lensing effects in a quantum field, which may lead to new insights in the elusive field of quantum gravity and other areas of physics.

The theory of relativity works well when you want to explain cosmic-scale phenomena — such as the gravitational waves.