Matter in space can arise out of what we perceive as nothing. But there is no such thing as a void in the Universe.

The Big Bang, traditionally considered the birth of the universe about 14 billion years ago, is being questioned. Physicist Bruno Bento and his team have proposed compelling research suggesting the universe may have always existed, and the Big Bang may merely be a significant event in its continuous evolution.

Bruno Bento and his colleagues set out to examine what the universe’s inception might have looked like without a Big Bang singularity. They grappled with contradictions arising when comparing accepted theories, particularly those dealing with quantum physics and general relativity. While quantum physics has accurately described three of the four fundamental forces of nature, it struggles to incorporate gravity. On the other hand, general relativity offers a comprehensive explanation of gravity, but falters when dealing with black holes’ centers and the universe’s genesis.

These contentious areas, termed “singularities,” are points in space-time where established physical laws cease to apply. Intriguingly, computations indicate an immense gravitational pull within singularities, even on a minuscule scale.

The quantum realm contains profound mysteries. Here, New Scientist editors have selected some of our most mind-bending feature-length articles about the deepest layer of reality we know.

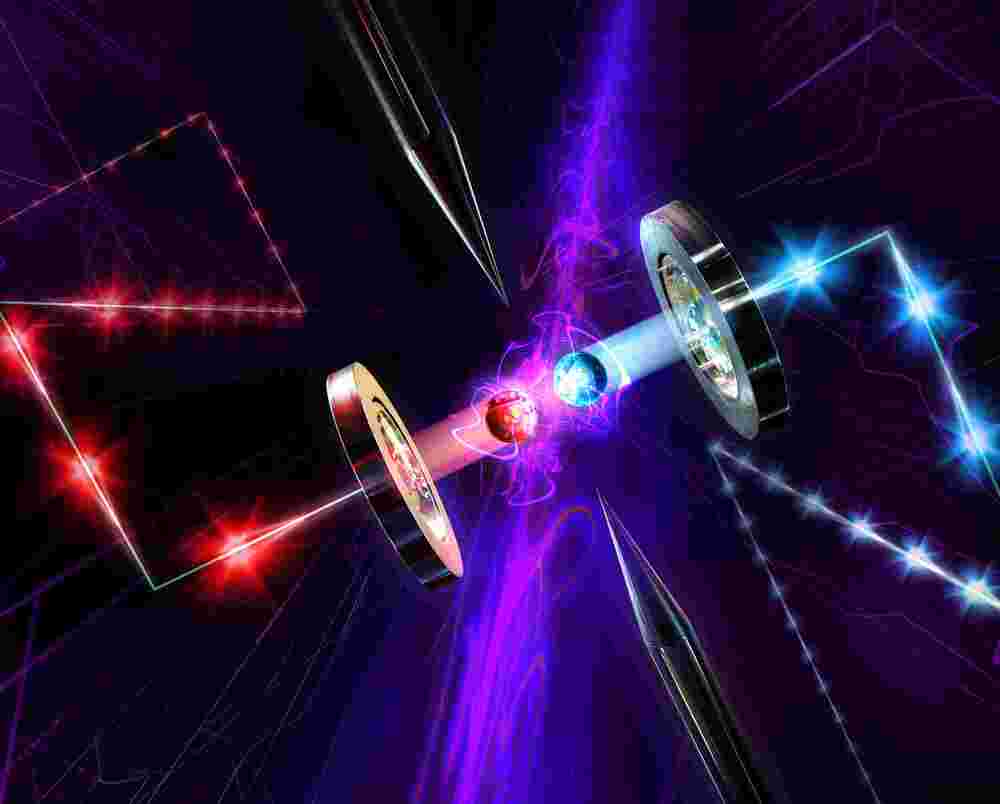

Physicists at the Universities of Innsbruck in Austria and Paris-Saclay in France have combined all the key functionalities of a long-distance quantum network into a single system for the first time. In a proof-of-principle experiment, they used this system to transfer quantum information via a so-called repeater node over a distance of 50 kilometres – far enough to indicate that the building blocks of practical, large-scale quantum networks may soon be within reach.

Quantum networks have two fundamental components: the quantum systems themselves, known as nodes, and one or more reliable connections between them. Such a network could work by connecting the quantum bits (or qubits) of multiple quantum computers to “share the load” of complex quantum calculations. It could also be used for super-secure quantum communications.

But building a quantum network is no easy task. Such networks often work by transmitting single photons that are entangled; that is, its quantum state is closely linked to the state of another quantum particle. Unfortunately, the signal from a single photon is easily lost over long distances. Carriers of quantum information can also lose their quantum nature in a process known as decoherence. Boosting these signals is therefore essential.

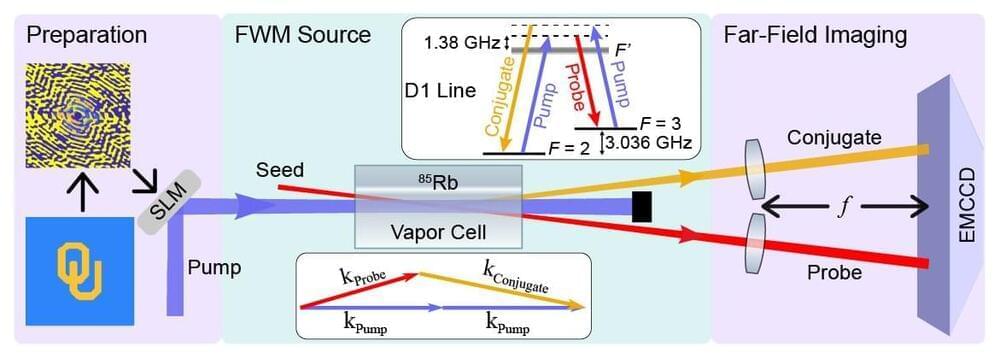

Researchers at the University of Oklahoma led a study recently published in Science Advances that proves the principle of using spatial correlations in quantum entangled beams of light to encode information and enable its secure transmission.

Light can be used to encode information for high-data rate transmission, long-distance communication and more. But for secure communication, encoding large amounts of information in light has additional challenges to ensure the privacy and integrity of the data being transferred.

Alberto Marino, the Ted S. Webb Presidential Professor in the Homer L. Dodge College of Arts, led the research with OU doctoral student and the study’s first author Gaurav Nirala and co-authors Siva T. Pradyumna and Ashok Kumar. Marino also holds positions with OU’s Center for Quantum Research and Technology and with the Quantum Science Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The Japanese electronics giant Sony has announced its first steps into quantum computing by joining other investment groups in a £42m venture in the UK quantum computing firm Quantum Motion. The move by the investment arm of Sony aims to boost the company’s expertise in silicon quantum chip development as well as to assist in a potential quantum computer roll-out onto the Japanese market.

Quantum Motion was founded in 2017 by scientists from University College London and the University of Oxford. It already raised a total of £20m via “seed investment” in 2017 and a “series A” investment in 2020. Quantum Motion uses qubits based on standard silicon chip technology and can therefore exploit the same manufacturing processes that mass-produces chips such as those found in smartphones.

A full-scale quantum computer, when built, is likely to require a million logical qubits to perform quantum-based calculations, with each logical qubit needing thousands of physical qubits to allow for robust error checking. Such demands will, however, require a huge amount of associated hardware if they are to be achieved. Quantum Motion claims that its technology could tackle this problem because it develops scalable arrays of qubits based on CMOS silicon technology to achieve high-density qubits.

The twentieth century was a truly exciting time in physics.

From 1905 to 1973, we made extraordinary progress probing the mysteries of the universe: special relativity, general relativity, quantum mechanics, the structure of the atom, the structure of the nucleus, enumerating the elementary particles.

Then, in 1973, this extraordinary progress… stopped.

I mean, where are the fundamental discoveries in the last 50 years equal to general relativity or quantum mechanics?

Why has there been no progress in physics since 1973?

For this high-budget, big-hair episode of The Last Theory, I flew all the way to Oxford to tell you why progress stopped, and why it’s set to start again: why progress in physics might be about to accelerate in the early twenty-first century in a way we haven’t seen since those heady days of the early twentieth century.

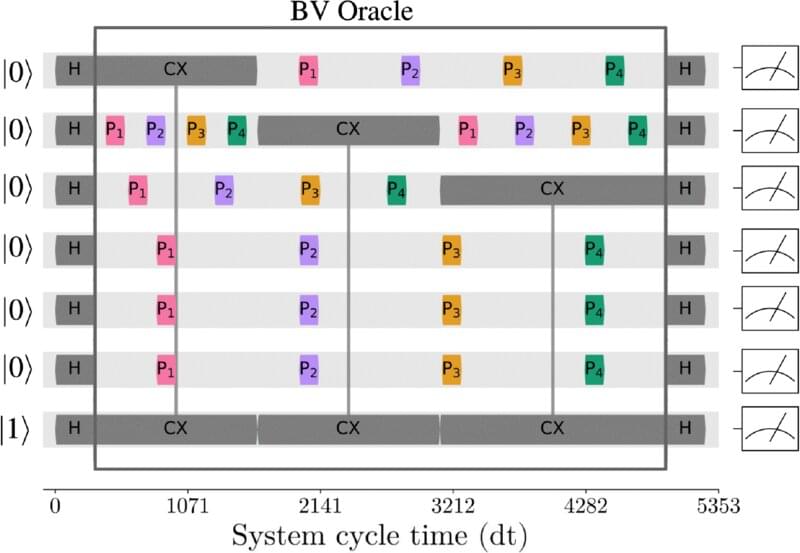

Daniel Lidar, the Viterbi Professor of Engineering at USC and Director of the USC Center for Quantum Information Science & Technology, and Dr. Bibek Pokharel, a Research Scientist at IBM Quantum, have achieved a quantum speedup advantage in the context of a “bitstring guessing game.” They managed strings up to 26 bits long, significantly larger than previously possible, by effectively suppressing errors typically seen at this scale. (A bit is a binary number that is either zero or one). Their paper is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Quantum computers promise to solve certain problems with an advantage that increases as the problems increase in complexity. However, they are also highly prone to errors, or noise. The challenge, says Lidar, is “to obtain an advantage in the real world where today’s quantum computers are still ‘noisy.’” This noise-prone condition of current quantum computing is termed the “NISQ” (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) era, a term adapted from the RISC architecture used to describe classical computing devices. Thus, any present demonstration of quantum speed advantage necessitates noise reduction.

The more unknown variables a problem has, the harder it usually is for a computer to solve. Scholars can evaluate a computer’s performance by playing a type of game with it to see how quickly an algorithm can guess hidden information. For instance, imagine a version of the TV game Jeopardy, where contestants take turns guessing a secret word of known length, one whole word at a time. The host reveals only one correct letter for each guessed word before changing the secret word randomly.