With anaesthetics and brain organoids, we are finally testing the idea that quantum effects explain consciousness – and the early results suggest this long-derided idea may have been misconstrued.

With anaesthetics and brain organoids, we are finally testing the idea that quantum effects explain consciousness – and the early results suggest this long-derided idea may have been misconstrued.

In this article, we argue that we can explain quantum stabilization of Morris-Thorne traversable wormholes through quantum mechanics. We suggest that the utilization of dark matter and dark energy, conceptualized as negative mass and negative energy tied to the universe’s information content, can stabilize these wormholes. This approach diverges from the original Morris-Thorne model by incorporating quantum effects, offering a credible and adequate source of the exotic matter needed to prevent wormhole collapse. We reassess the wormholes’ stability and information content considering the new calculated revised vacuum energy based on the mass of bit of information. This new calculation makes the wormholes more viable within our universe’s limits.

Researchers have used quantum computers to solve difficult physics problems. But claims of a quantum “advantage” must wait as ever-improving algorithms boost the performance of classical computers.

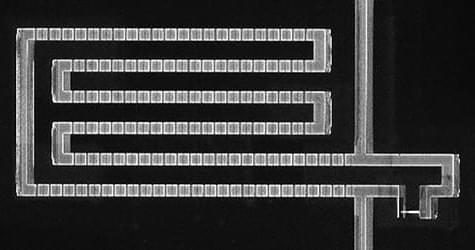

Quantum computers have plenty of potential as tools for carrying out complex calculations. But exactly when their abilities will surpass those of their classical counterparts is an ongoing debate. Recently, a 127-qubit quantum computer was used to calculate the dynamics of an array of tiny magnets, or spins—a problem that would take an unfathomably long time to solve exactly with a classical computer [1]. The team behind the feat showed that their quantum computation was more accurate than nonexact classical simulations using state-of-the-art approximation methods. But these methods represented only a small handful of those available to classical-computing researchers. Now Joseph Tindall and his colleagues at the Flatiron Institute in New York show that a classical computer using an algorithm based on a so-called tensor network can produce highly accurate solutions to the spin problem with relative ease [2].

Scientists used a laser-based technique to reveal hidden quantum properties of the material Ta2NiSe5, potentially advancing the development of quantum light sources.

Certain materials have desirable properties that are hidden, and just as you would use a flashlight to see in the dark, scientists can use light to uncover these properties.

Researchers at the University of California San Diego have used an advanced optical technique to learn more about a quantum material called Ta2NiSe5 (TNS). Their work was published in the journal Nature Materials.

When a high-energy photon strikes a proton, secondary particles diverge in a way that indicates that the inside of the proton is maximally entangled. An international team of physicists with the participation of the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Cracow has just demonstrated that maximum entanglement is present in the proton even in those cases where pomerons are involved in the collisions.

Eighteen months ago, it was shown that different parts of the interior of the proton must be maximally quantum entangled with each other. This result, achieved with the participation of Prof. Krzysztof Kutak from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow and Prof. Martin Hentschinski from the Universidad de las Americas Puebla in Mexico, was a consequence of considerations and observations of collisions of high-energy photons with quarks and gluons in protons and supported the hypothesis presented a few years earlier by professors Dimitri Kharzeev and Eugene Levin.

Now, in a paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters, an international team of physicists has presented a complementary analysis of entanglement for collisions between photons and protons in which secondary particles (hadrons) are produced by a process called diffractive deep inelastic scattering. The main question was: does entanglement also occur among quarks and gluons in these cases, and if so, is it also maximal?

4 reviewer reports (4 anonymous)

13 citations in the Web of Science Core Collection.

Classical and Quantum Gravity Published by IOP Publishing Indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection Engages in Transparent Peer Review.

Jonathan Oppenheim at University College London has developed a new theoretical framework that aims to unify quantum mechanics and classical gravity – without the need for a theory of quantum gravity. Oppenheim’s approach allows gravity to remain classical, while coupling it to the quantum world by a stochastic (random) mechanism.

\r \r.

For decades, theoretical physicists have struggled to reconcile Einstein’s general theory of relativity – which describes gravity — with quantum theory, which describes just about everything else in physics. A fundamental problem is that quantum theory assumes that space–time is fixed, whereas general relativity says that space–time changes dynamically in response to the presence of massive objects.

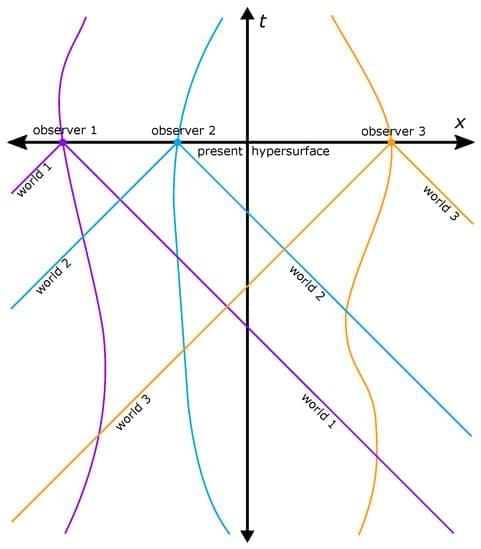

In 1948, Schwinger developed a local Lorentz-covariant formulation of relativistic quantum electrodynamics in space-time which is fundamentally inconsistent with any delocalized interpretation of quantum mechanics. An interpretation compatible with Schwinger’s theory is presented, which reproduces all of the standard empirical predictions of conventional delocalized quantum theory in configuration space. This is an explicit, unambiguous, and Lorentz-covariant “local hidden variable theory” in space-time, whose existence proves definitively that such theories are possible. This does not conflict with Bell’s theorem because it is a local many-worlds theory.