Quantum chaos focuses on the quantum manifestations of classical chaos. A characteristic of classical chaos is the exponential sensitivity of the dynamics with respect to infinitesimal changes in the initial conditions. Thus, to classify classical dynamics it is sufficient to follow phase space trajectories starting infinitesimally close to each other and to determine the evolution of their distances with respect to each other with time. Because of the uncertainty relation, this is no longer possible in the corresponding quantum system. One important aspect of quantum chaos is the understanding of features of the classical dynamics in terms of the fluctuation properties in the energy spectra of closed quantum systems or of the fluctuations exhibited by the scattering matrix elements describing open ones. The fluctuation properties are predicted to be universal, that is, to be the same for systems belonging to the same universality class and exhibiting the same chaotic behavior in the corresponding classical dynamics and to be describable by random matrix theory. Furthermore, random-matrix models that had been developed for the scattering matrix associated with compound-nuclear reactions have been shown to be applicable to quantum-chaotic scattering processes. A second important aspect within the field of quantum chaos concerns the semiclassical approach. In this context, one of the most important achievements was the periodic orbit theory pioneered by Gutzwiller, which led to understanding the impact of the classical dynamics on the properties of the quantum system in terms of purely classical quantities. The focus of research within the field of quantum chaos has been extended to relativistic quantum systems and to many-body quantum systems with focus on random matrix theory and the semiclassical approach. In distinction to single-particle systems, many-body systems like atomic nuclei do not have a classical analogue. In recent years different measures of chaos and models have been developed. Here, a prominent model is the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model which serves as a paradigm for the study of quantum chaos in strongly interacting many-body systems. The school is aimed at PhD students, post-docs and outstanding master students and the first part will provide a survey of single-and many-body quantum chaos and applications based on random-matrix theory and the semiclassical approach. The second part of the school will focus on current aspects of research in the context of many-body quantum chaos. There is no registration fee and limited funds are available for travel and local expenses. Organizers: Hilda Cerdeira (IFT-UNESP, Brazil) Barbara Dietz-Pilatus (Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Republic of Korea)

Category: quantum physics – Page 375

Chaos: The real problem with quantum mechanics

Check out the math & physics courses that I mentioned (many of which are free!) and support this channel by going to https://brilliant.org/Sabine/ where you can create your Brilliant account. The first 200 will get 20% off the annual premium subscription. You have probably heard people saying that the problem with quantum mechanics is that it’s non-local or that it’s impossible to understand or that it defies common sense. But the problem is much simpler, it’s that quantum mechanics is a linear theory and therefore doesn’t correctly reproduce chaos. Physicists have known this for a long time but it’s rarely discussed. In this video I explain what the problem is, what physicists have done to try and solve it, and why that solution doesn’t work. Subscribe to my weekly science newsletter: https://sabinehossenfelder.com/ You find the estimate for Saturn’s moon Hyperion in Zurek’s review https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0105127 A much easier to digest and more readable review by Michael Berry is here: https://michaelberryphysics.files.wor… you can find a brief summary on Sean Carroll’s blog https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/… 0:00 Intro 0:27 The trouble with Hyperion 4:04 The alleged solution 6:02 The trouble with the solution 7:46 What a real solution requires 10:31 Sponsor message.

How Chaos Control Is Changing The World

Try out my quantum mechanics course (and many others on math and science) on Brilliant using the link https://brilliant.org/sabine. You can get started for free, and the first 200 will get 20% off the annual premium subscription.

Physicists have known that it’s possible to control chaotic systems without just making them even more chaotic since the 1990s. But in the past 10 years this field has really exploded thanks to machine learning.

The full video from TU Wien with the inverted double pendulum is here: • Double Pendulum on a Cart.

The video with the AI-trained racing car is here: • NeuroRacer.

And the full Boston Dynamics video is here: • Do You Love Me?

👉 Transcript and References on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

Lamb Lecture 2024 ‘Quantum information, chaos, and space-time’

Quantum gravity aims to find a description of spacetime and gravity that obeys the rules of quantum mechanics.

Quantum Internet Unleashed With HiFi’s Laser Breakthrough

The expansion of fiber optics is progressing worldwide, which not only increases the bandwidth of conventional Internet connections, but also brings closer the realization of a global quantum Internet. The quantum internet can help to fully exploit the potential of certain technologies. These include much more powerful quantum computing through the linking of quantum processors and registers, more secure communication through quantum key distribution or more precise time measurements through the synchronization of atomic clocks.

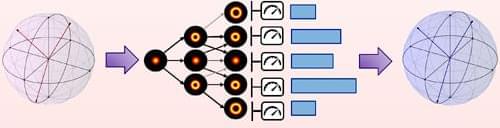

However, the differences between the glass fiber standard of 1,550 nm and the system wavelengths of the various quantum bits (qubits) realized to date represent a hurdle, because those qubits are mostly in the visible or near-infrared spectral range. Researchers want to overcome this obstacle with the help of quantum frequency conversion, which can specifically change the frequencies of photons while retaining all other quantum properties. This enables conversion to the 1,550 nm telecom range for low-loss, long-range transmission of quantum states.

Powerful New Tool Ushers In New Era of Quantum Materials Research

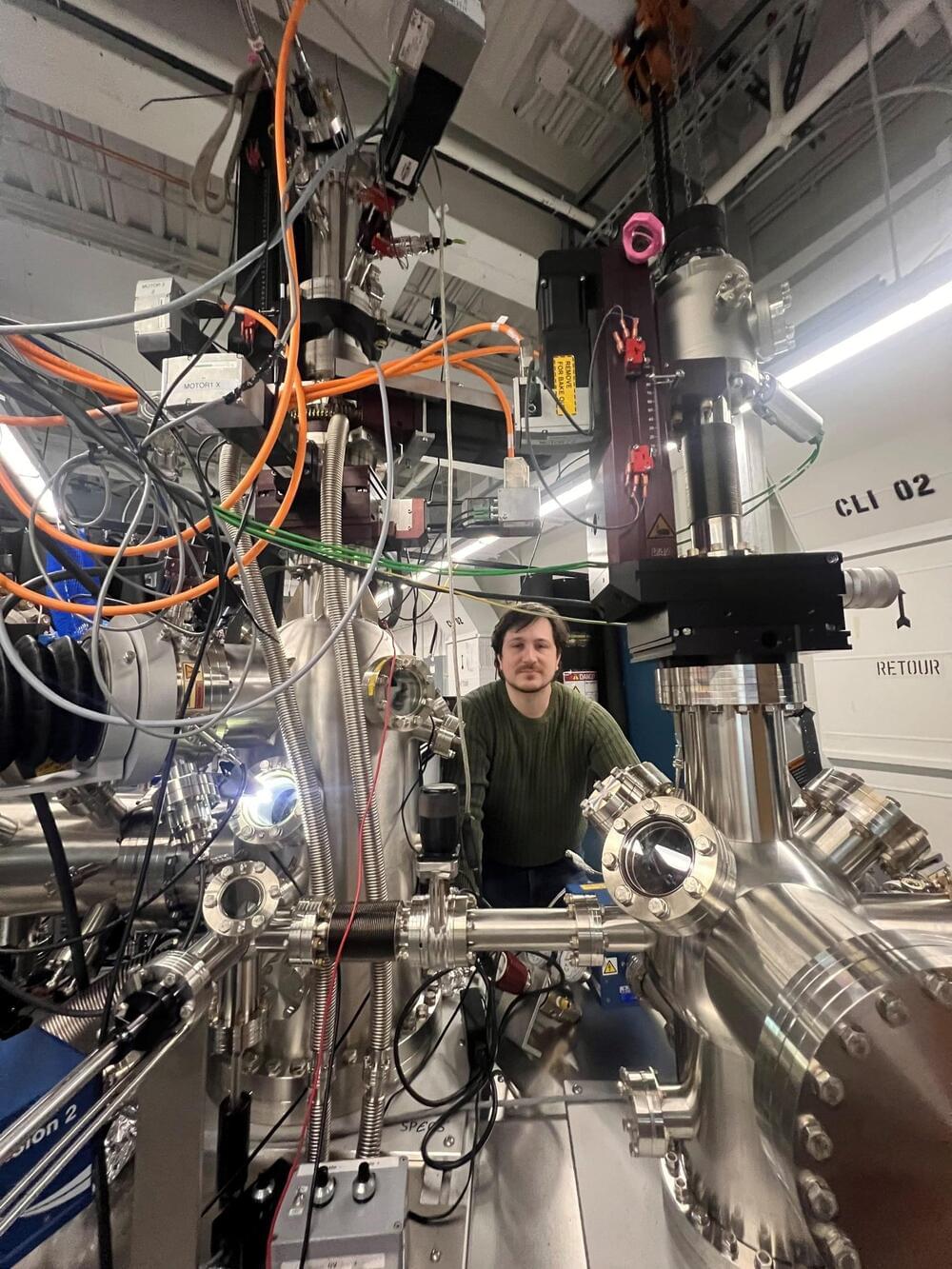

Professor Fabio Boschini (above) and his colleagues are at the forefront of research in quantum materials, employing time-and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES) to drive technological breakthroughs in industries like mining, energy, and healthcare. Their recent work, demonstrates how TR-ARPES enhances the understanding and manipulation of material properties through light-matter interaction. Credit: Fabio Boschini (INRS)

Research into quantum materials is leading to revolutionary breakthroughs and is set to propel technological progress that will transform industries such as mining, energy, transportation, and medical technology.

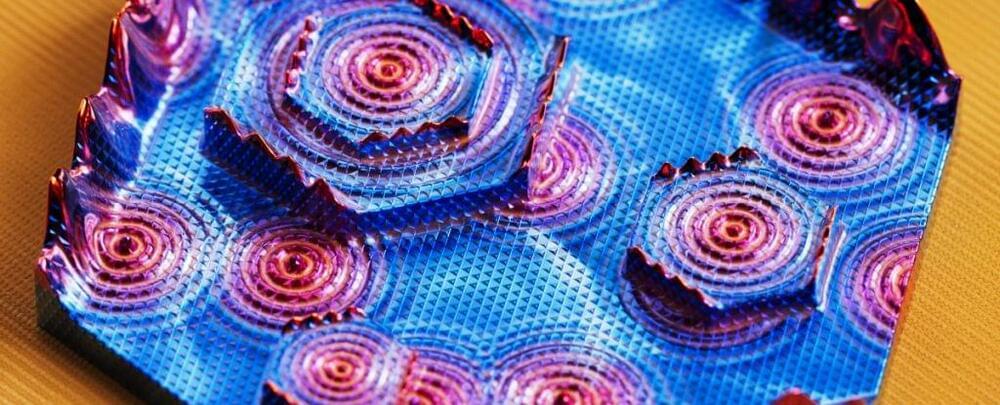

A technique called time-and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES) has emerged as a powerful tool, allowing researchers to explore the equilibrium and dynamical properties of quantum materials via light-matter interaction.

Never-Before-Seen Quantum Hybrid State Discovered on Arsenic Surface

Physicists have just found something no one expected, lurking on the surface of an arsenic crystal.

While undertaking a study of quantum topology – the wave-like behavior of particles combined with the mathematics of geometry – a team found a strange hybrid of two quantum states, each describing a different means of current.

“This finding was completely unexpected,” says physicist M. Zahid Hasan of Princeton University. “Nobody predicted it in theory before its observation.”

Enhanced Interactions Using Quantum Squeezing

A quantum squeezing method can enhance interactions between quantum systems, even in the absence of precise knowledge of the system parameters.

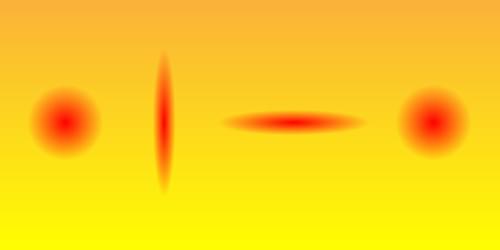

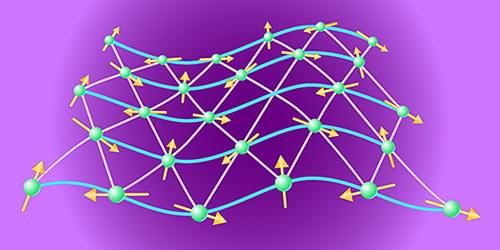

Squeezed states are an important class of nonclassical states, where quantum fluctuations can be reduced in one property of a system, such as position. However, at the same time, according to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, quantum fluctuations increase in the conjugate property, in this case momentum. The ability to suppress noise in at least one variable is valuable in a wide range of areas in quantum technologies. Now Shaun Burd at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Colorado, and colleagues have experimentally demonstrated a squeezing-based enhancement method that requires no preknowledge of the system’s parameters [1]. The researchers use a trapped-ion system (Fig. 1) and show that they can amplify the motion of the ion using a combination of squeezing procedures. This experimental research can stimulate other novel applications of squeezing, for example, in dark matter searches.

For decades, quantum squeezing has played a central role in high-precision quantum measurements, such as gravitational-wave detection [2, 3] and nondemolition qubit readout [4– 6]. The methods typically involve applying a field or inserting an optical element that reduces the fluctuations in one observable. The measurements of this squeezed observable can beat the standard quantum limit and thus enable a significant improvement in the detection sensitivity or the readout signal-to-noise ratio.

Viewing a Quantum Spin Liquid through QED

A numerical investigation has revealed a surprising correspondence between a lattice spin model and a quantum field theory.

The search for a quantum spin liquid (QSL) in a real magnetic material has been at the forefront of condensed-matter physics since this exotic quantum state was first proposed over half a century ago. Meanwhile, theorists continue to grapple with understanding what rich physics might emerge from this state. Now Alexander Wietek of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Germany and his collaborators have made a significant advance toward that goal. Through numerical simulations, they have presented a compelling numerical case that the spectrum of elementary excitations of a well-studied QSL has a one-to-one correspondence with the spectrum of excitations of a well-studied quantum field theory [1]. If a real QSL is discovered or fabricated, the correspondence opens the prospect of testing theories from particle physics with condensed-matter systems.