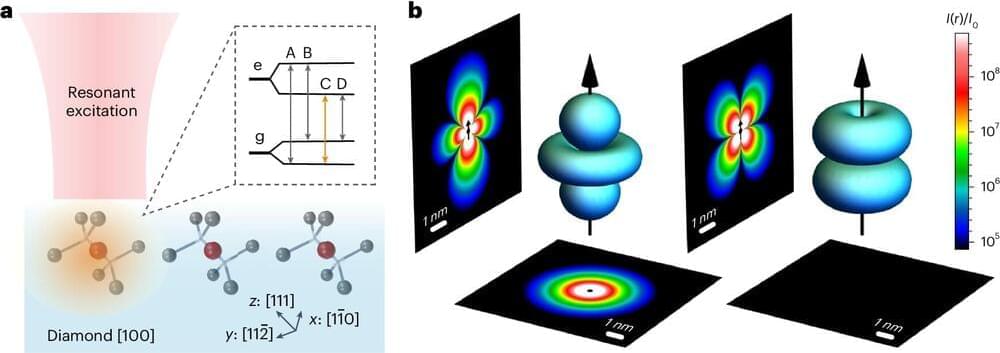

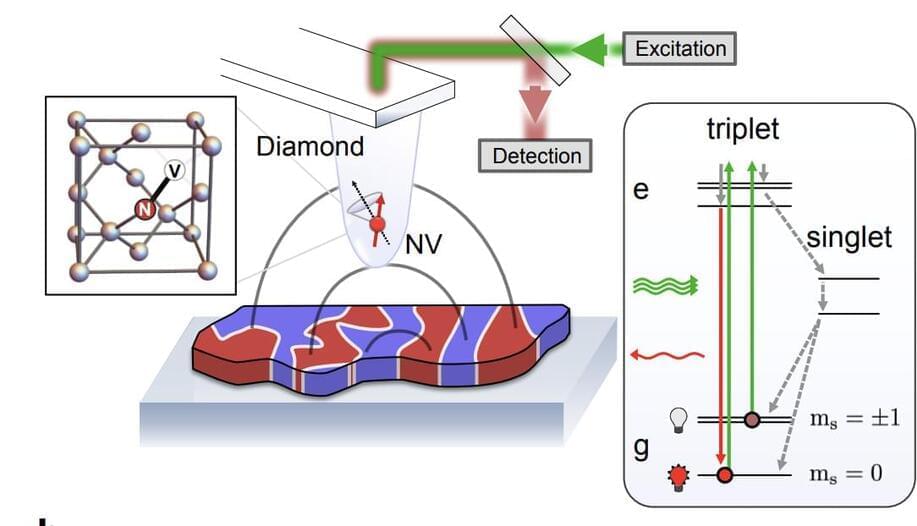

Researchers from Princeton University, University of California Santa Barbara, University of Basel, and ETH Zurich have discovered new applications for nitrogen vacancy (NV) centre quantum sensors in condensed matter physics. These sensors, which offer nanoscale resolution across a wide range of temperatures, have been used to measure static magnetic fields in condensed matter systems.

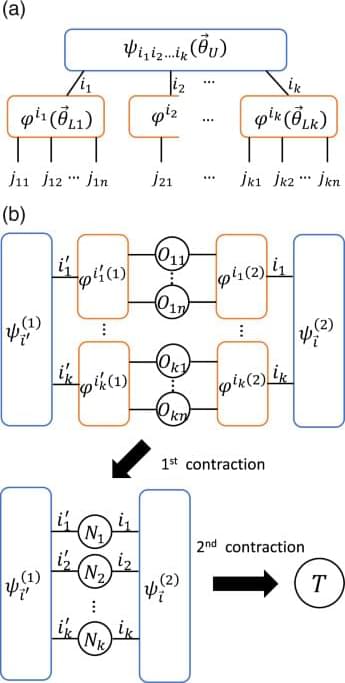

NV centres can probe beyond average magnetic fields, enabling high precision noise sensing in diverse systems. They offer several advantages over other nanoscale probes, including the ability to probe both static and dynamic properties in a momentum and frequency-resolved way.

Condensed matter physics is a field that studies the physical properties of condensed phases of matter, such as solids and liquids. Recently, researchers from Princeton University, University of California Santa Barbara, University of Basel, and ETH Zurich have discovered new opportunities in this field for nanoscale quantum sensors, specifically nitrogen vacancy (NV) centre quantum sensors. These sensors offer unique advantages in studying condensed matter systems due to their quantitative, noninvasive, physically robust nature, and their ability to offer nanoscale resolution across a wide range of temperatures.