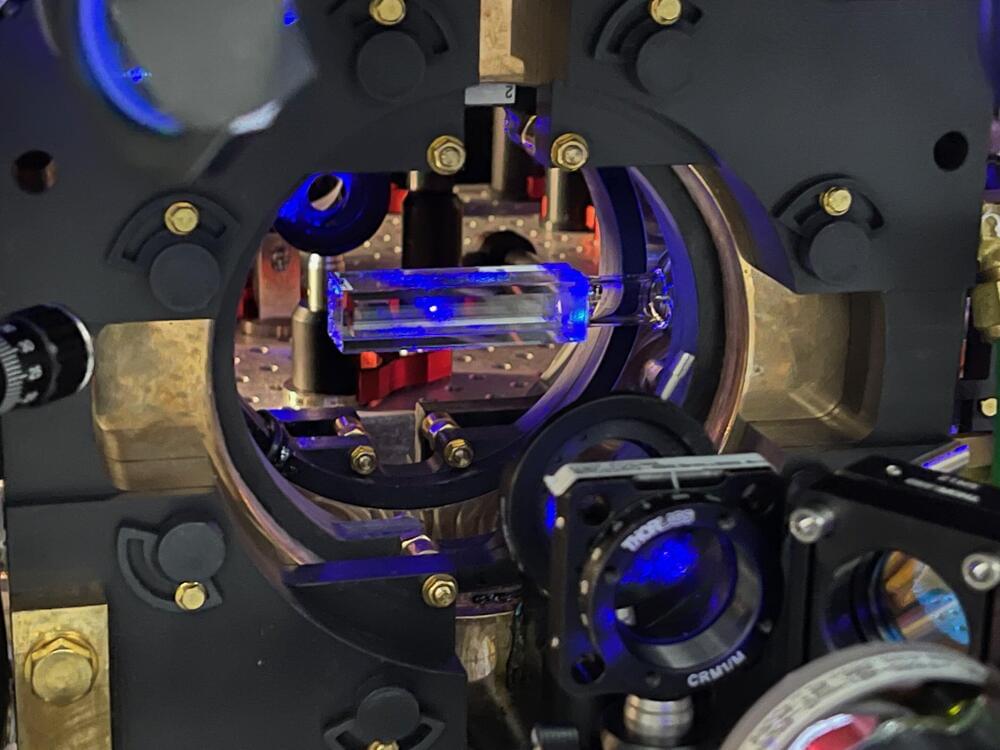

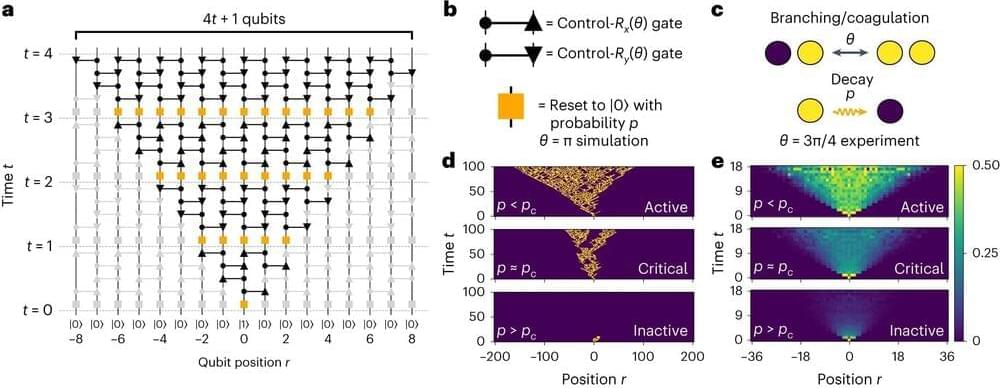

A team of computer engineers from quantum computer maker Quantinuum, working with computer scientists from Microsoft, has found a way to greatly reduce errors when running experiments on a quantum computer. The combined group has published a paper describing their work and results on the arXiv preprint server.

Computer scientists have been working for several years to build a truly useful quantum computer that could achieve quantum supremacy. Research has come a long way, most of which has involved adding more qubits.

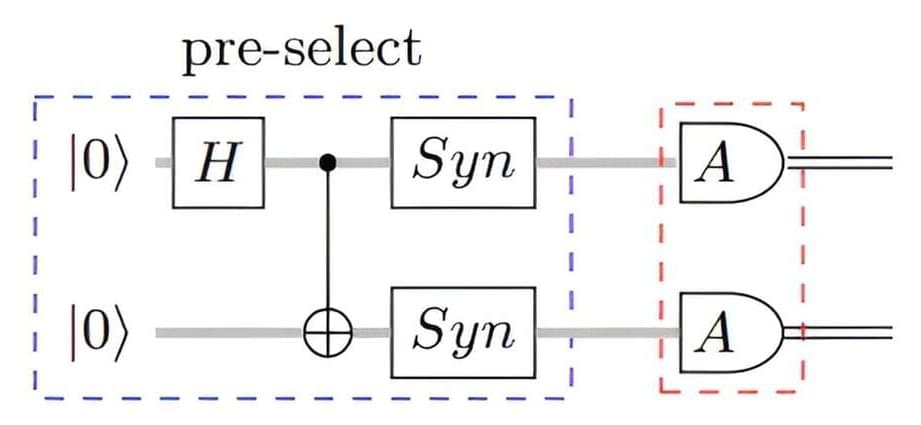

But such research has been held up by one main problem—quantum computers make a lot of errors. To overcome this problem, researchers have been looking for ways to reduce the number of errors or to correct those that are made before results are produced.