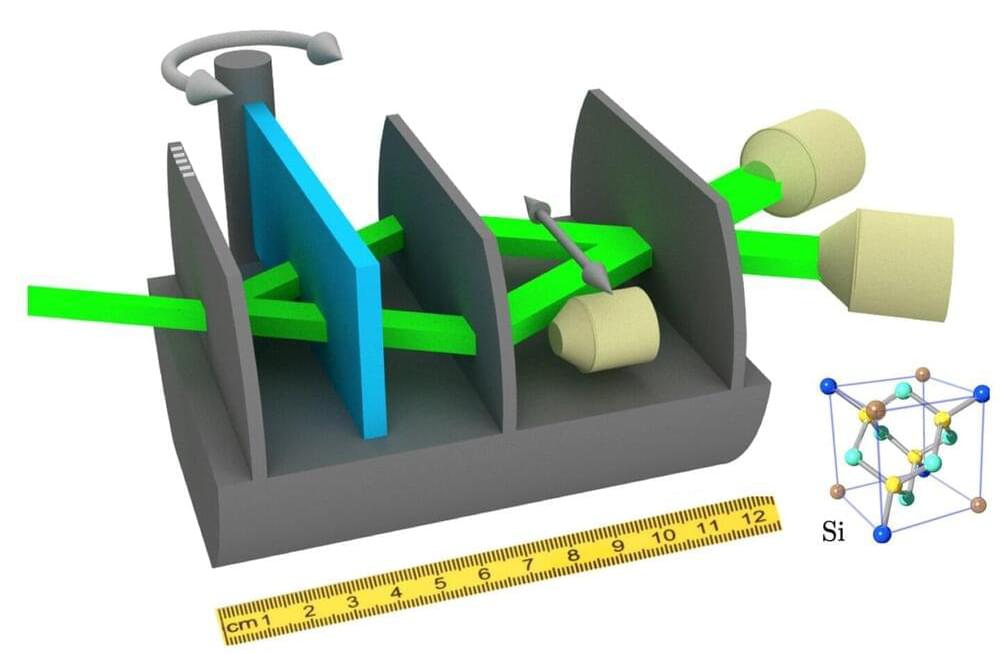

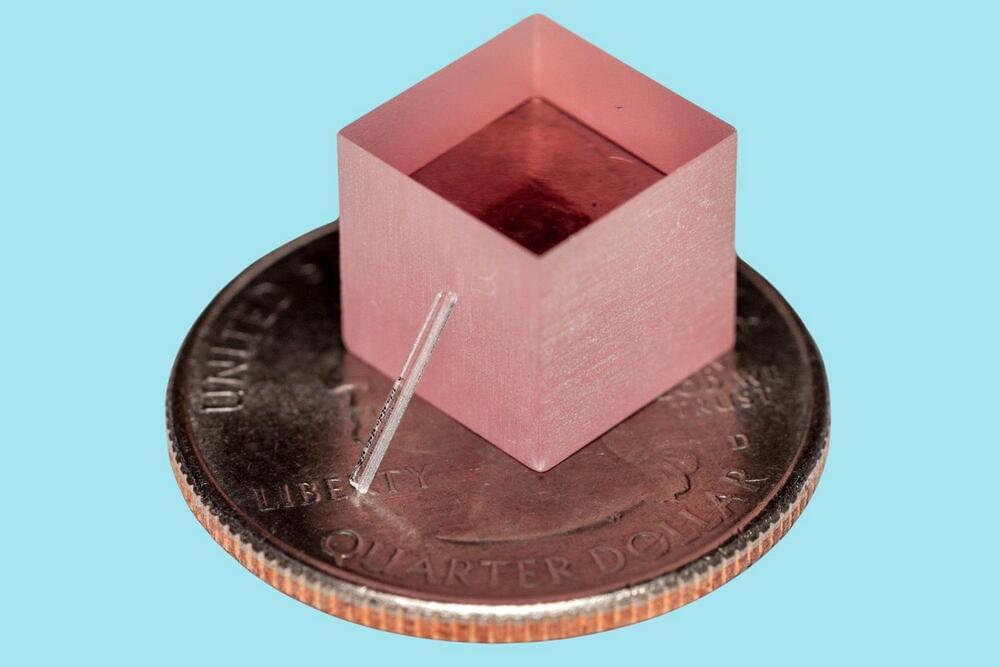

In a single leap from tabletop to the microscale, engineers at Stanford University have produced the world’s first practical titanium-sapphire laser on a chip.

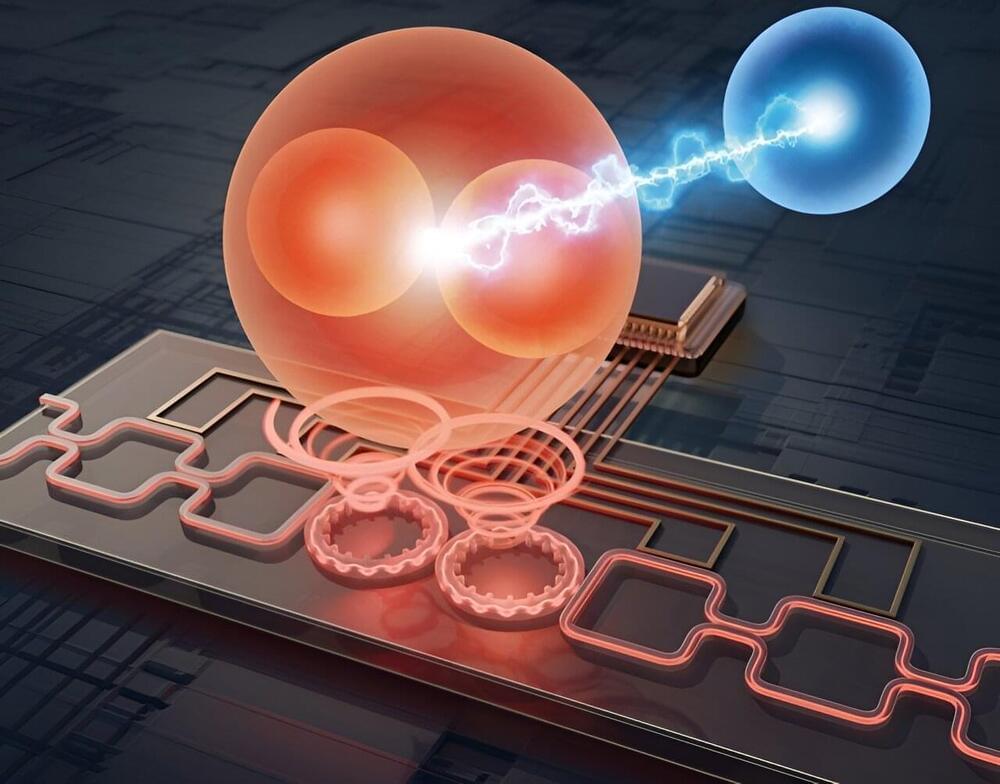

Researchers have developed a chip-scale Titanium-sapphire laser that is significantly smaller and less expensive than traditional models, making it accessible for broader applications in quantum optics, neuroscience, and other fields. This new technology is expected to enable labs to have hundreds of these powerful lasers on a single chip, fueled by a simple green laser pointer.

As lasers go, those made of Titanium-sapphire (Ti: sapphire) are considered to have “unmatched” performance. They are indispensable in many fields, including cutting-edge quantum optics, spectroscopy, and neuroscience. But that performance comes at a steep price. Ti: sapphire lasers are big, on the order of cubic feet in volume. They are expensive, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars each. And they require other high-powered lasers, themselves costing $30,000 each, to supply them with enough energy to function.