Boost your knowledge in AI and emerging technologies with Brilliant’s engaging courses. Enjoy 30 days free and 20% off a premium subscription at https://brilliant.org/FutureBusinessTech.

In this video, we explore 20 emerging technologies changing our future, including super-intelligent AI companions, radical life extension through biotechnology and gene editing, and programmable matter. We also cover advancements in flying cars, the quantum internet, autonomous AI agents, and other groundbreaking innovations transforming the future.

🎁 5 Free ChatGPT Prompts To Become a Superhuman: https://bit.ly/3Oka9FM

✨ Join This Channel: / @futurebusinesstech.

00:07 Super Intelligent AI Companions.

04:27 Radical Life Extension.

08:40 Programmable Matter.

11:33 Flying Cars.

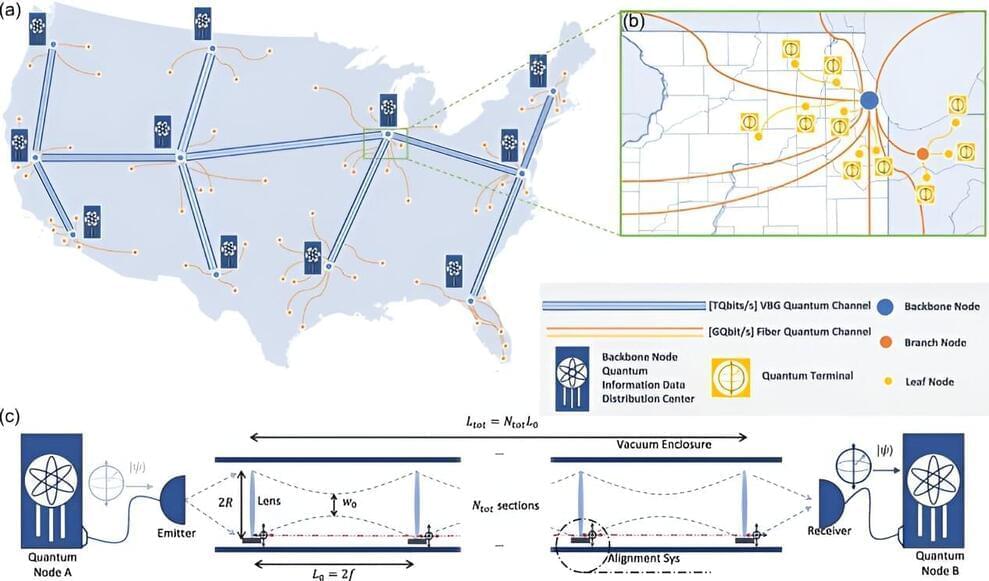

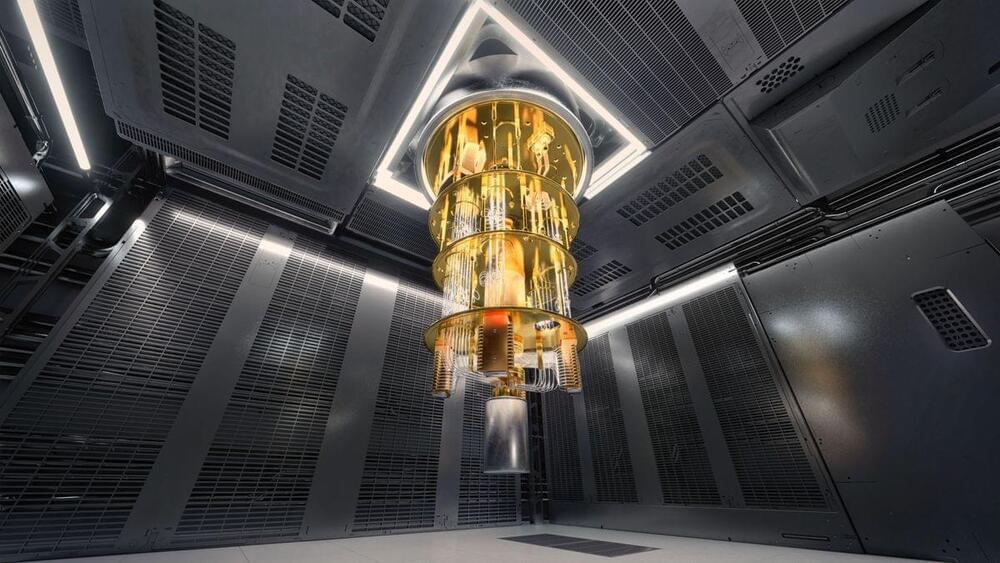

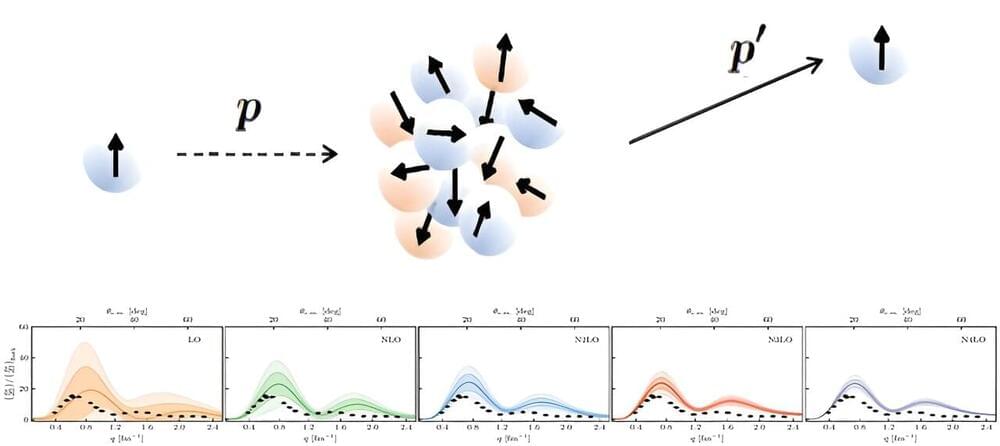

16:29 Quantum Internet.

20:34 Autonomous AI Agents.

25:21 Hypersonic Aircraft And Missiles.

29:19 Invisibility Suits.

33:45 Human Brain Simulations.

37:02 Synthetic Biology.

40:54 AI-Enabled Warfare.

44:58 Solar Sail Technology.

49:42 Bionic Eyes.

53:20 Swarm Robotics.

56:40 Room-Temperature Superconductors.

01:01:42 Optical Computing.

01:05:59 Graphene Technology.

01:11:01 Artificial Trees.

01:15:07 Web 3.0

01:18:03 Vertical Farming.

💡 Future Business Tech explores AI, emerging technologies, and future technologies.

SUBSCRIBE: https://bit.ly/3geLDGO