The observation of a previously unseen photon delay in the production of quantum light has implications for the development of quantum technologies.

The multiverse offers no escape from our reality—which might be a very good thing.

As memes go, it wasn’t particularly viral. But for a couple of hours on the morning of November 6, the term “darkest timeline” trended in Google searches, and several physicists posted musings on social media about whether we were actually in it. All the probabilities expressed in opinion polls and prediction markets had collapsed into a single definite outcome, and history went from “what might be” to “that just happened.” The two sides in this hyperpolarized U.S. presidential election had agreed on practically nothing—save for their shared belief that its outcome would be a fateful choice between two diverging trajectories for our world.

A new route to materials with complex disordered magnetic properties at the quantum level has been produced by scientists for the first time. The material, based on a framework of ruthenium, fulfills the requirements of the Kitaev quantum spin liquid state—an elusive phenomenon that scientists have been trying to understand for decades.

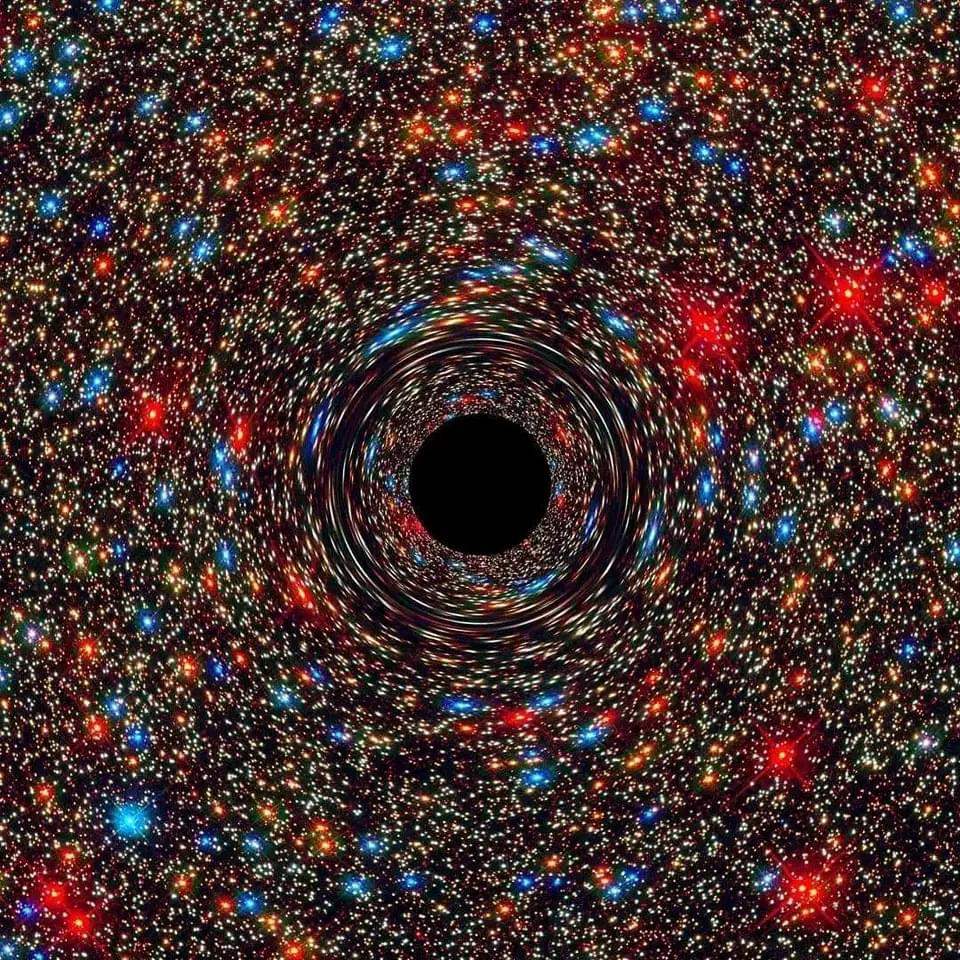

What if our universe is not the only one? What if it is just a tiny bubble inside a much larger and more complex reality? This is the idea behind the bubble universe theory, which suggests that our universe is one of many possible universes that exist inside a black hole.

What is a bubble universe?

A bubble universe is a hypothetical region of space that has different physical laws and constants than the rest of the multiverse. The multiverse is the collection of all possible universes that exist or could exist. A bubble universe could form when a quantum fluctuation creates a tiny pocket of space with different properties than its surroundings. This pocket could then expand and inflate into a large and isolated universe, like a bubble in a glass of water.

Physicists have learned a lot about the makeup of the universe over the past century and have developed many theories to explain how everything works. Two of the biggest are Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which describes the visible or classical world, and quantum theory, which describes the quantum world.

But one thing physicists do not understand completely is gravity. They also do not know if it fits into general relativity or quantum physics. Figuring out what gravity is would go a long way toward the development of a grand unified theory of physics, which would tie the two fields together—one of the biggest goals in the physics world.

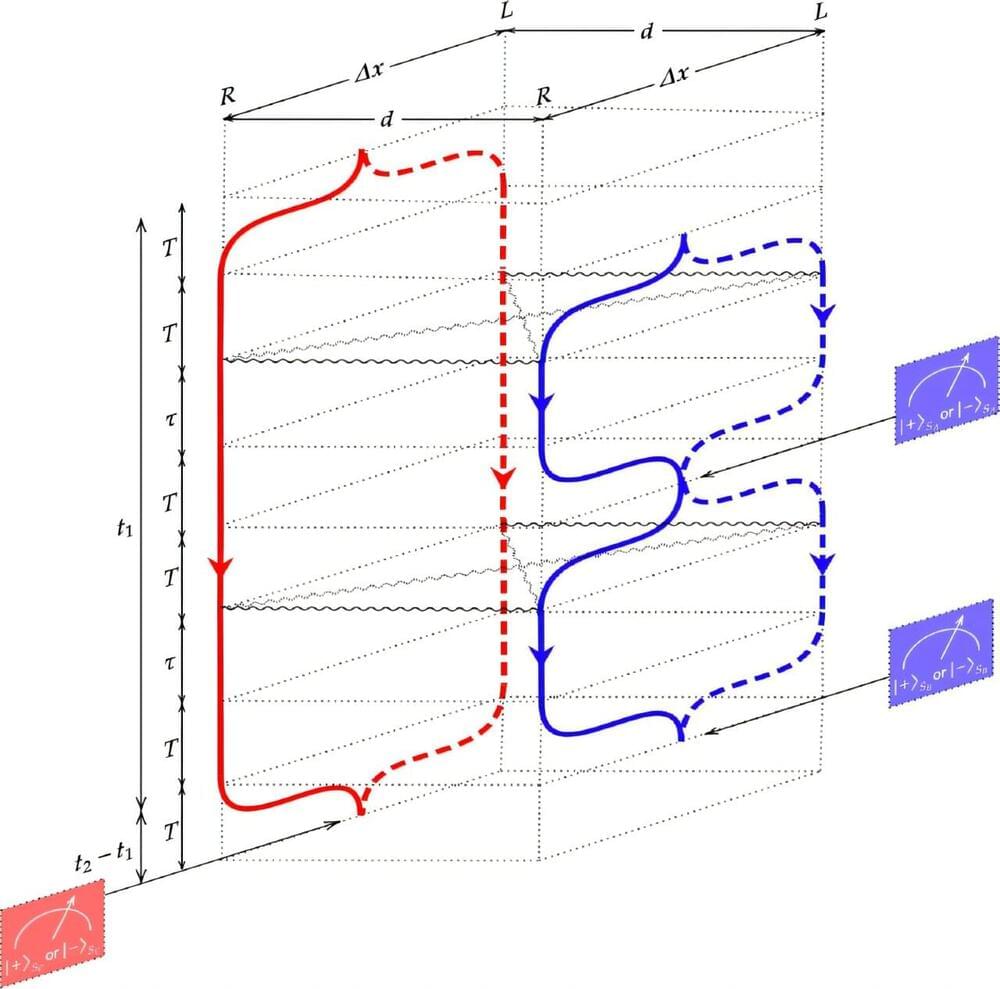

In this new research, the team has developed an idea for a so-called table-top experiment that could be used to show whether gravity is changed when measured—if so, that would give strong evidence that it is a quantum property.

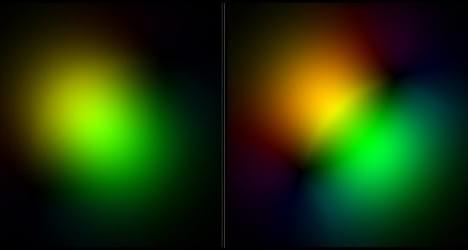

A group of South Korean researchers has successfully developed an integrated quantum circuit chip using photons (light particles). It is a system capable of controlling eight photons using a photonic integrated-circuit chip. With this system, they can explore various quantum phenomena, such as multipartite entanglement resulting from the interaction of the photons.

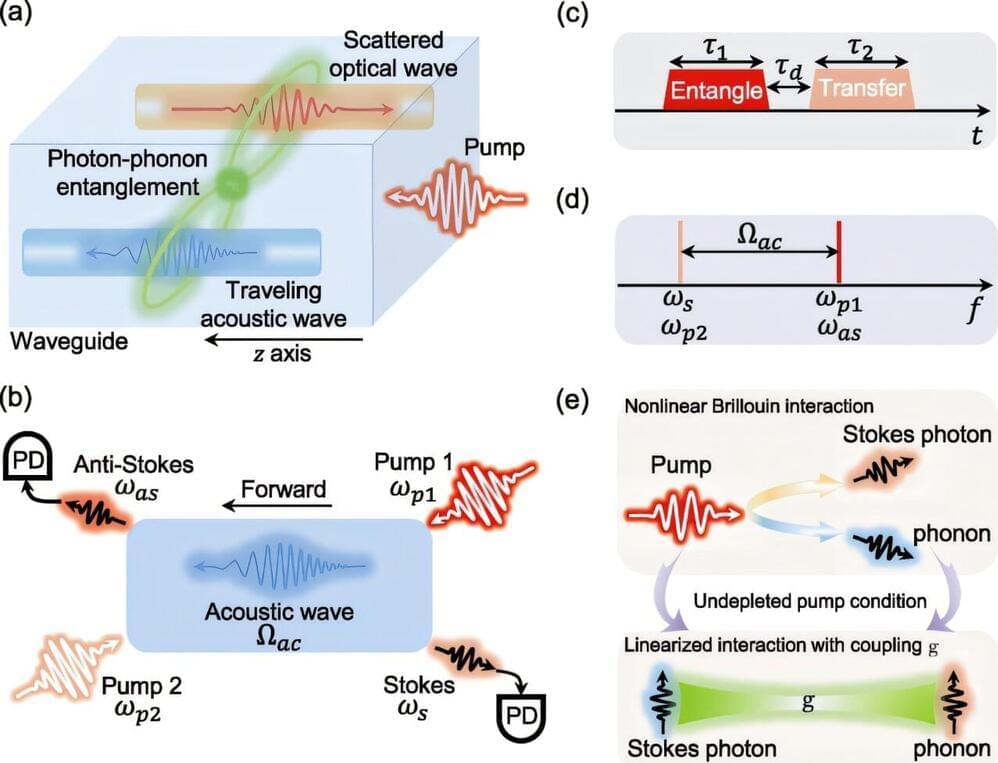

Photons, however, are volatile. Therefore, feasible alternatives are being sought for certain applications, such as quantum memory or quantum repeater schemes. One such alternative is the acoustic domain, where quanta are stored in acoustic or sound waves.

Scientists at the MPL have now indicated a particularly efficient way in which photons can be entangled with acoustic phonons: While the two quanta travel along the same photonic structures, the phonons move at a much slower speed. The underlying effect is the optical nonlinear effect known as Brillouin-Mandelstam scattering. It is responsible for coupling quanta at fundamentally different energy scales.

In their study, the scientists showed that the proposed entangling scheme can operate at temperatures in the tens of Kelvin. This is much higher than those required by standard approaches, which often employ expensive equipment such as dilution fridges. The possibility of implementing this concept in optical fibers or photonic integrated chips makes this mechanism of particular interest for use in modern quantum technologies.

In our increasingly interconnected digital world, the foundations of secure communication and data privacy are built upon cryptographic algorithms that have stood the test of time.

Discover how quantum computing threatens current API security and learn strategies to prepare your APIs for Q-Day by adopting post-quantum cryptography solutions.

I believe that nanotechnology could be imbedded into paper so a paper computer could give one the same information as a smartphone but at pennies per smartphone. Right now we can print out 3D copies of paper phones and other things next would be nanotechnology made of paper with quantum mechanical engineering.

Irish company Mcor’s unique paper-based 3D printers make some very compelling arguments. For starters, instead of expensive plastics, they build objects out of cut-and-glued sheets of standard 80 GSM office paper. That means printed objects come out at between 10–20 percent of the price of other 3D prints, and with none of the toxic fumes or solvent dips that some other processes require.

Secondly, because it’s standard paper, you can print onto it in full color before it’s cut and assembled, giving you a high quality, high resolution color “skin” all over your final object. Additionally, if the standard hard-glued object texture isn’t good enough, you can dip the final print in solid glue, to make it extra durable and strong enough to be drilled and tapped, or in a flexible outer coating that enables moving parts — if you don’t mind losing a little of your object’s precision shape.

The process is fairly simple. Using a piece of software called SliceIt, a 3D model is cut into paper-thin layers exactly the thickness of an 80 GSM sheet. If your 3D model doesn’t include color information, you can add color and detail to the model through a second piece of software called ColorIt.