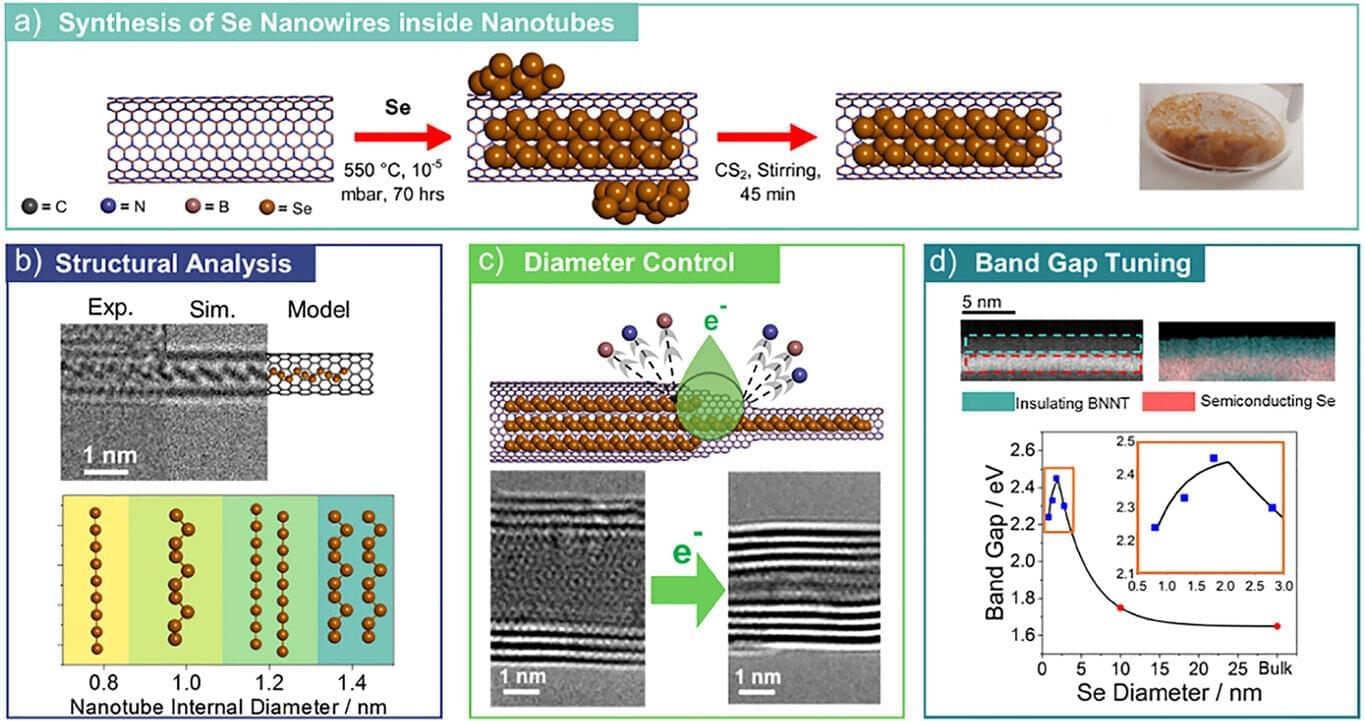

Professor Andrei Khlobystov, School of Chemistry, University of Nottingham, said, “We have investigated the ultimate limit for nanowire size while preserving useful electronic properties. This is possible for selenium because the phenomenon of quantum confinement can be effectively balanced by distortions in the atomic structure, thus allowing the band gap to remain within a useful range.”

The researchers hope that these new materials will be incorporated into electronic devices in the future. Accurately tuning the band gap of selenium by changing the diameter of the nanowire could lead to the design of a variety of customized electronic devices using only a single element.