Quantum chip beats classical AI in real-world test, saving energy and hinting at a greener AI future.

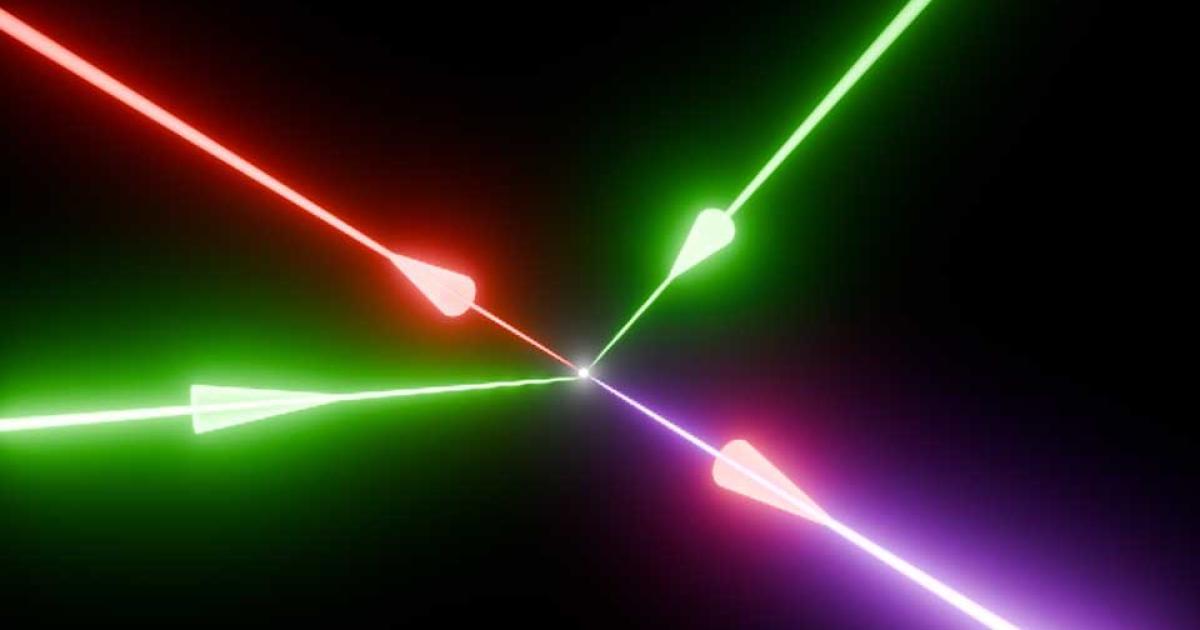

Physicists at the University of Oxford have successfully simulated how light interacts with empty space – a phenomenon once thought to belong purely to the realm of science fiction. The simulations recreated a bizarre phenomenon predicted by quantum physics, where light appears to be generated from darkness. The findings pave the way for real-world laser facilities to experimentally confirm bizarre quantum phenomena. The results have been published in Communications Physics.

Using advanced computational modelling, a research team led by the University of Oxford, working in partnership with the Instituto Superior Técnico in the University of Lisbon, has achieved the first-ever real-time, three-dimensional simulations of how intense laser beams alter the ‘quantum vacuum’ – a state once assumed to be empty, but which quantum physics predicts is full of virtual electron-positron pairs.

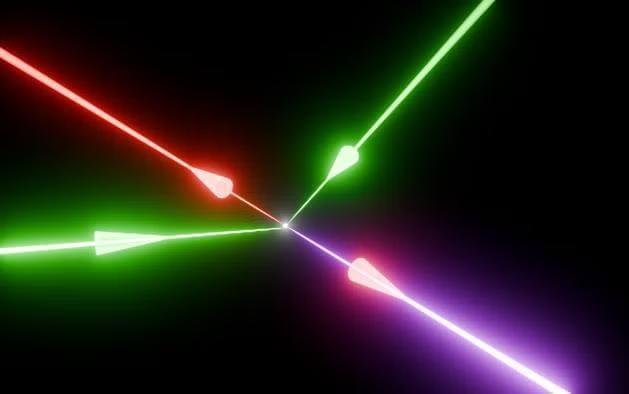

Excitingly, these simulations recreate a bizarre phenomenon predicted by quantum physics, known as vacuum four-wave mixing. This states that the combined electromagnetic field of three focused laser pulses can polarise the virtual electron-positron pairs of a vacuum, causing photons to bounce off each other like billiard balls – generating a fourth laser beam in a ‘light from darkness’ process. These events could act as a probe of new physics at extremely high intensities.

In a new study, physicists at the University of Colorado Boulder have used a cloud of atoms chilled down to incredibly cold temperatures to simultaneously measure acceleration in three dimensions—a feat that many scientists didn’t think was possible.

The device, a new type of atom “interferometer,” could one day help people navigate submarines, spacecraft, cars and other vehicles more precisely.

“Traditional atom interferometers can only measure acceleration in a single dimension, but we live within a three-dimensional world,” said Kendall Mehling, a co-author of the new study and a graduate student in the Department of Physics at CU Boulder. “To know where I’m going, and to know where I’ve been, I need to track my acceleration in all three dimensions.”

Randomness is incredibly useful. People often draw straws, throw dice or flip coins to make fair choices. Random numbers can enable auditors to make completely unbiased selections. Randomness is also key in security; if a password or code is an unguessable string of numbers, it’s harder to crack. Many of our cryptographic systems today use random number generators to produce secure keys.

But how do you know that a random number is truly random?

Classical computer algorithms can only create pseudorandom numbers, and someone with enough knowledge of the algorithm or the system could manipulate it or predict the next number. An expert in sleight of hand could rig a coin flip to guarantee a heads or tails result. Even the most careful coin flips can have bias; with enough study, their outcomes could be predicted.

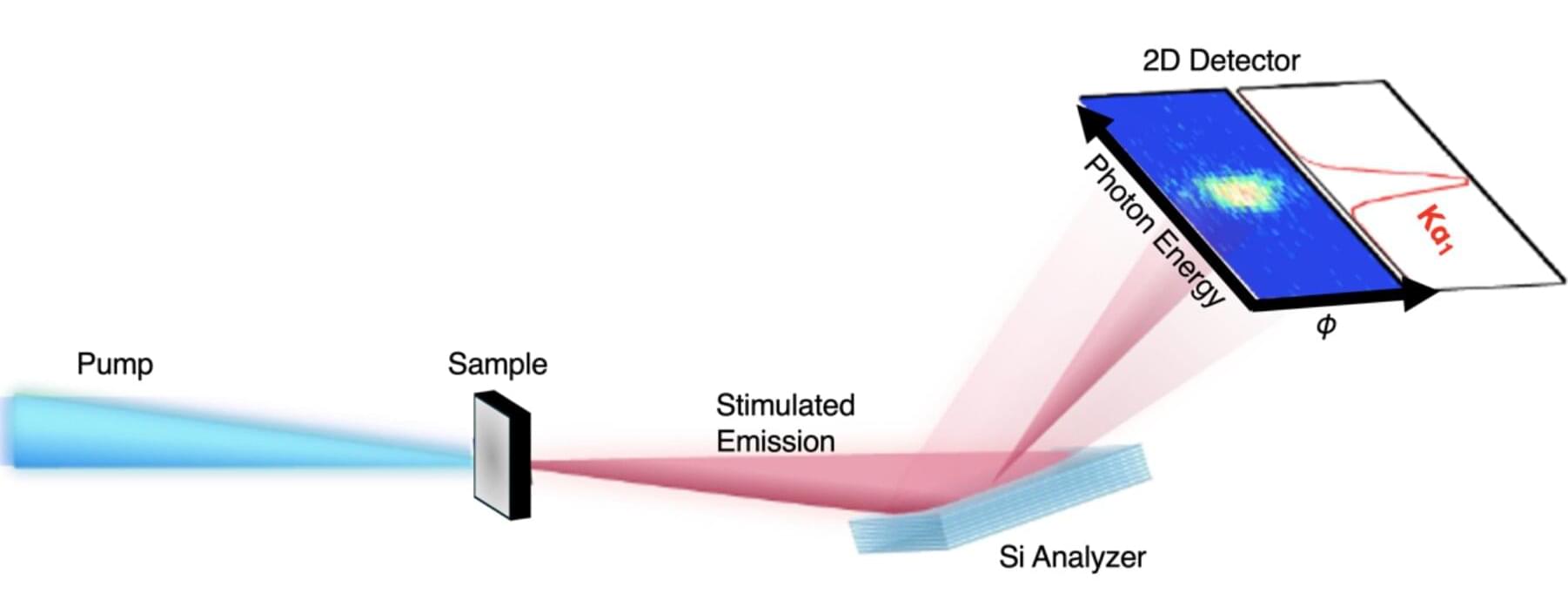

Once only a part of science fiction, lasers are now everyday objects used in research, health care and even just for fun. Previously available only in low-energy light, lasers are now available in wavelengths from microwaves through X-rays, opening a range of different downstream applications.

In a study published in Nature, an international collaboration led by scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison has generated the shortest hard X-ray pulses to date through the first demonstration of strong lasing phenomena.

The resulting pulses can lead to several potential applications, from quantum X-ray optics to visualizing electron motion inside molecules.

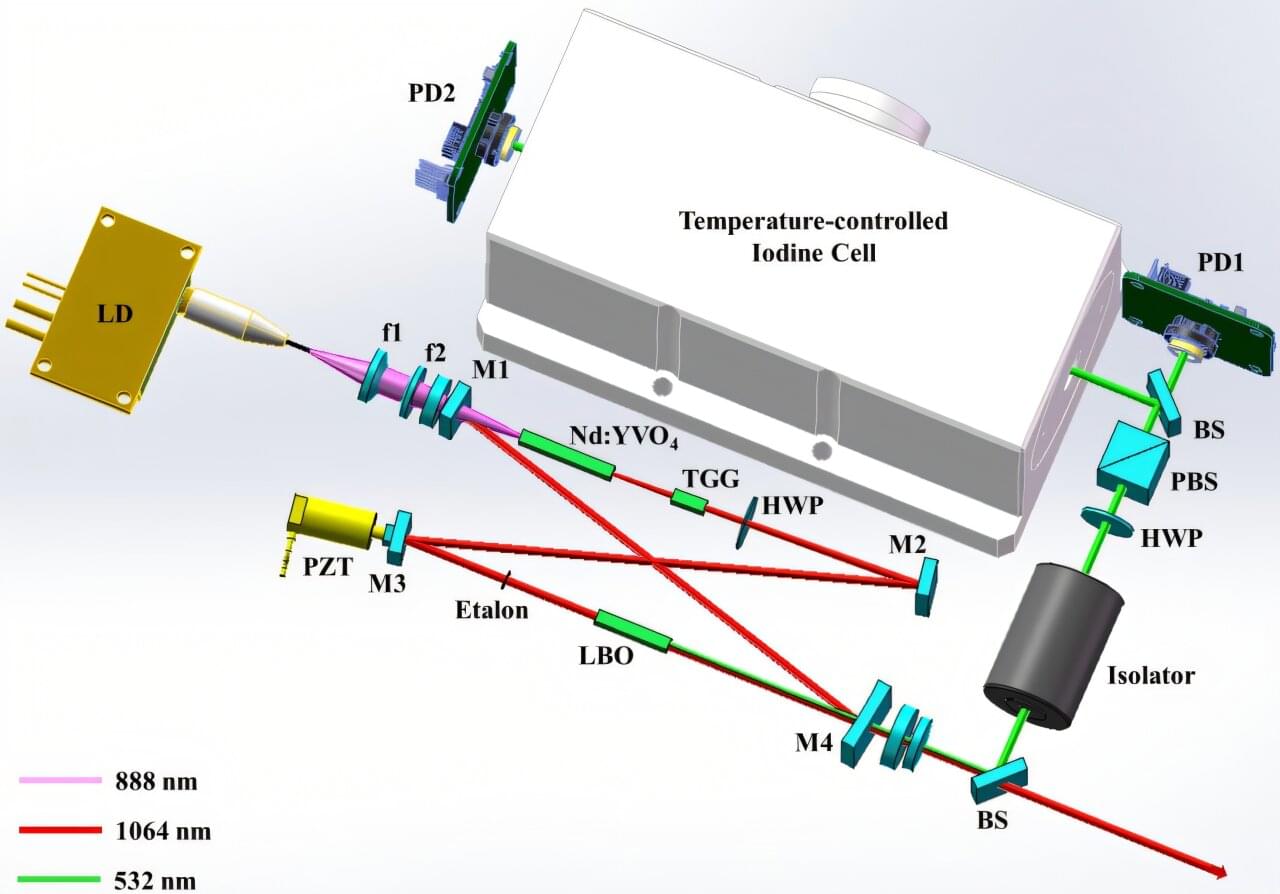

A research team led by Prof. Zhang Tianshu at the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has developed a compact all-solid-state continuous-wave (CW) single-longitudinal-mode (SLM) laser with high frequency stability using iodine-based frequency locking, advancing its application in atmospheric remote sensing and environmental monitoring. The study is published in Optics and Laser Technology.

CW SLM lasers are widely used in areas such as laser amplification, gravitational wave detection, and quantum optics. They also play a key role in atmospheric remote sensing and environmental monitoring. These applications require not only SLM laser output but also high frequency stability, which current semiconductor and fiber lasers struggle to provide due to limited environmental adaptability.

In this study, the team introduced a ring resonator structure combined with iodine molecular absorption frequency locking technology. By locking the laser frequency to the flank of specific iodine absorption lines and employing feedback control to adjust the resonator length, they achieved long-term frequency stability.

Scientists have demonstrated after decades of theorising how light interacts with vacuum, recreating a bizarre phenomenon predicted by quantum physics.

Oxford University physicists ran simulations to test how intense laser beams alter vacuum, a state once thought to be empty but predicted by quantum physics to be full of fleeting, temporary particle pairs.

Classical physics predicts that light beams pass through each other undisturbed. But quantum mechanics holds that even what we know as vacuum is always brimming with fleeting particles, which pop in and out of existence, causing light to be scattered.

We’ve questioned that model and tackled questions from a different angle – by looking inward instead of outward.

Instead of starting with an expanding universe and asking how it began, we considered what happens when an over-density of matter collapses under gravity.

Prof Gaztanaga explained that the theory developed by his team of researchers worked within the principles of quantum mechanics and the model could be tested scientifically.

How can the strange properties of quantum particles be exploited to perform extremely accurate measurements? This question is at the heart of the research field of quantum metrology. One example is the atomic clock, which uses the quantum properties of atoms to measure time much more accurately than would be possible with conventional clocks.

However, the fundamental laws of quantum physics always involve a certain degree of uncertainty. Some randomness or a certain amount of statistical noise has to be accepted. This results in fundamental limits to the accuracy that can be achieved. Until now, it seemed to be an immutable law that a clock twice as accurate requires at least twice as much energy.

Now a team of researchers from TU Wien, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, and the University of Malta has demonstrated that special tricks can be used to increase accuracy exponentially. The crucial point is using two different time scales—similar to how a clock has a second hand and a minute hand.

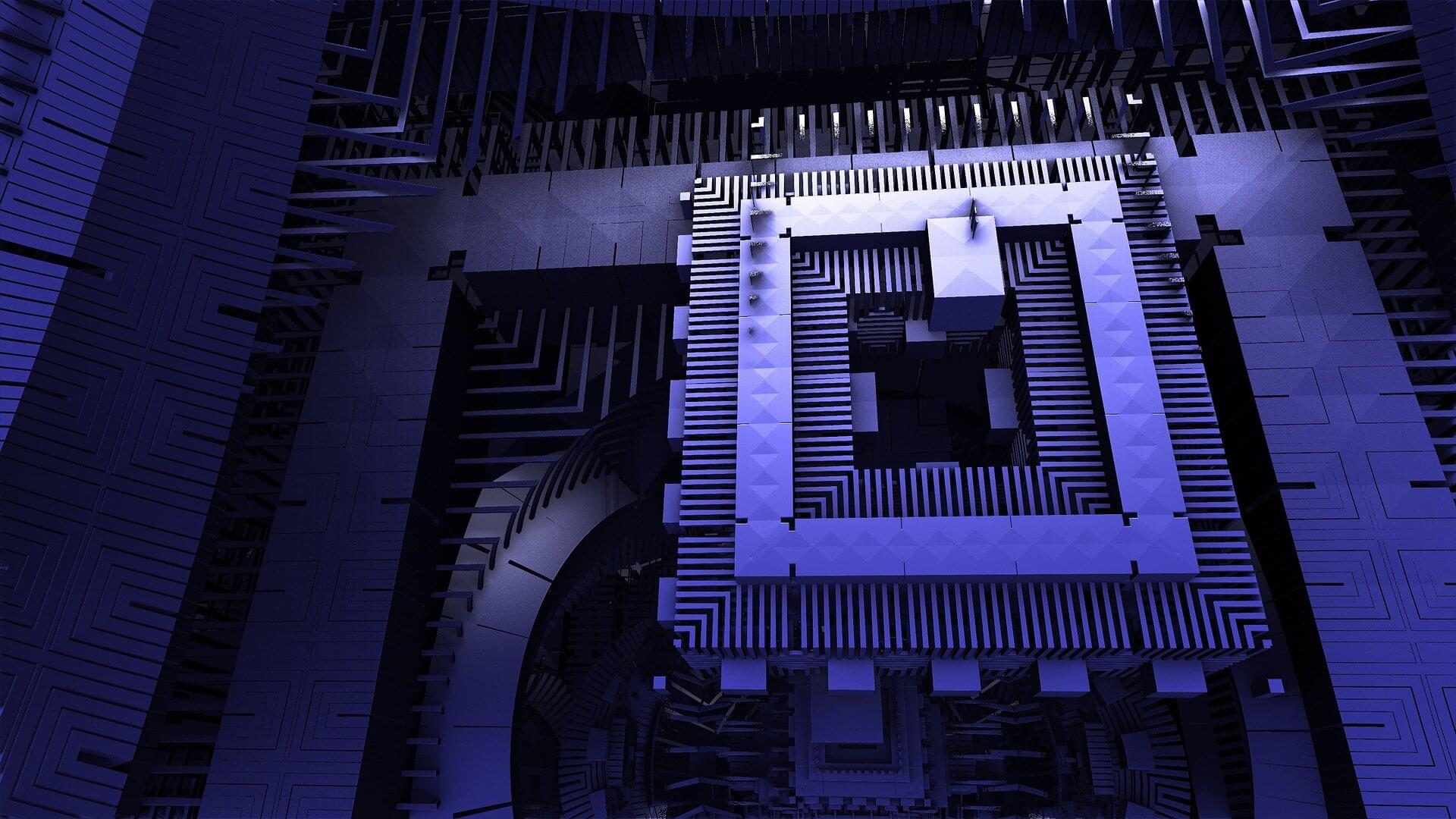

Technology veteran IBM on Tuesday laid out a plan to have a “practical” quantum computer tackling big problems before the end of this decade.

Current quantum computers are still experimental and face significant challenges, including high error rates. Companies like IBM, Google, and others are working to build more stable and scalable quantum systems.

Real-world innovations that quantum computing has the potential to tackle include developing better fuels, materials, pharmaceuticals, or even new elements. However, delivering on that promise has always seemed some way off.