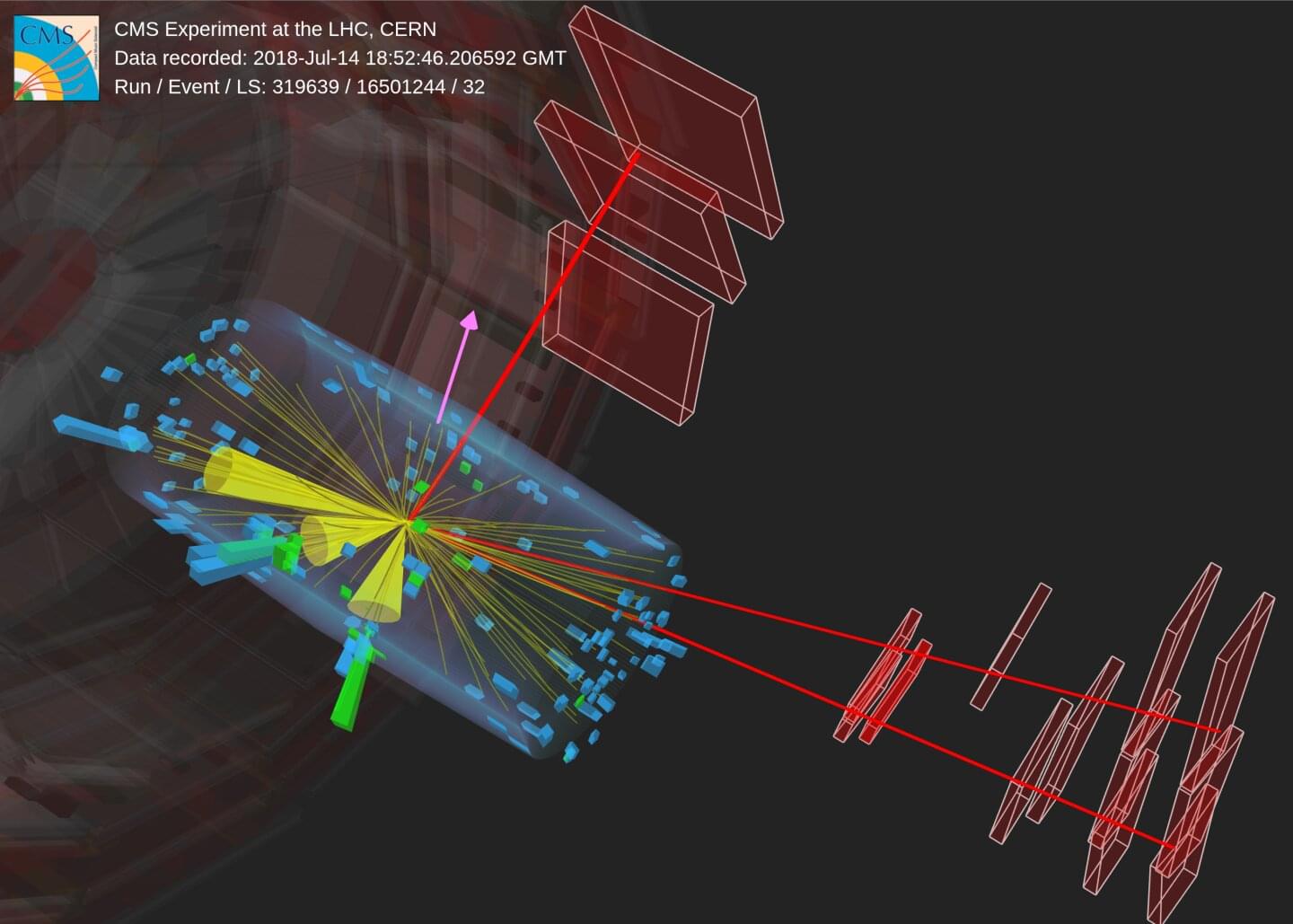

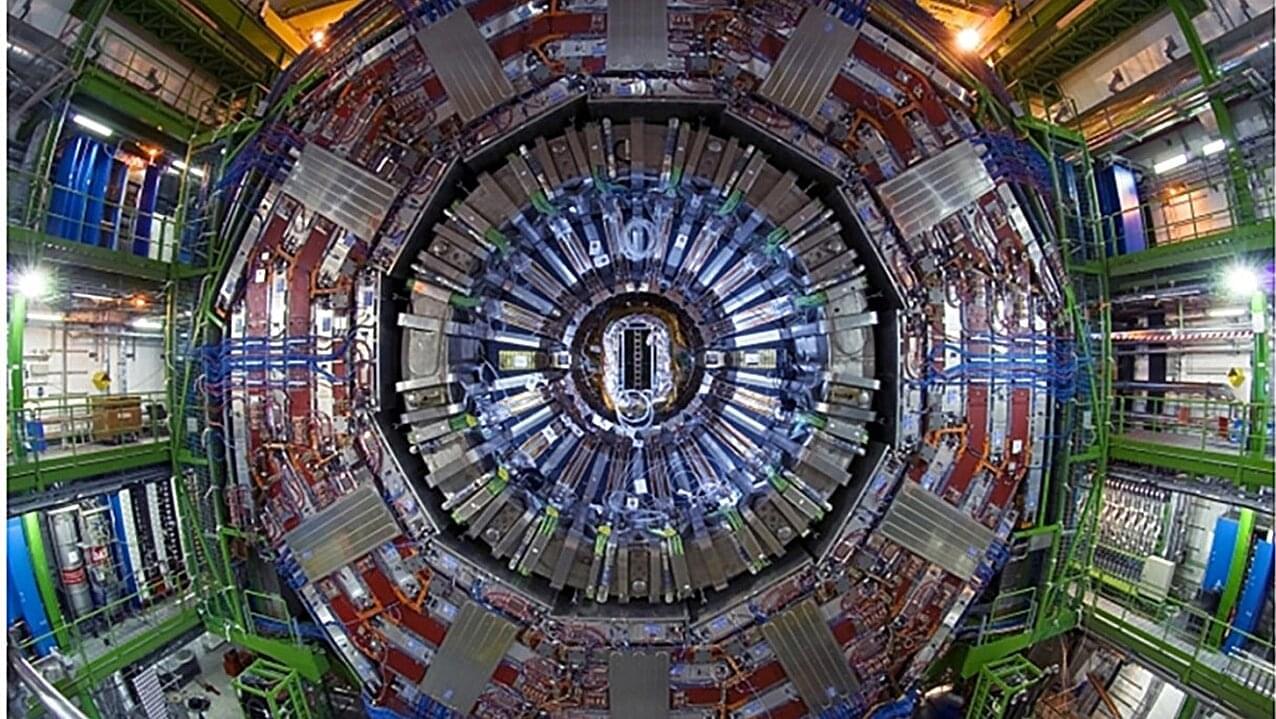

The experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) detect rare events on a daily basis, but some are exceptionally rare, such as this latest result from the CMS collaboration. For the first time, the collaboration has observed the production of a single top quark along with a W and a Z boson, an extremely rare process that happens only once every trillion proton collisions. Finding this event in the LHC data is like searching for a needle in a haystack the size of an Olympic stadium.

The creation of a top quark, a W boson and a Z boson, known as tWZ production, opens up a new window for understanding the fundamental forces of nature. By closely studying tWZ production, physicists can investigate how the top quark interacts with the electroweak force, which is carried by the W and Z bosons.

In addition, the top quark is the heaviest known fundamental particle, meaning that it has the strongest interaction with the Higgs field, so, studying the tWZ process could give us a deeper understanding of the Higgs mechanism. It could also point us to signs of new phenomena and physics beyond the Standard Model.