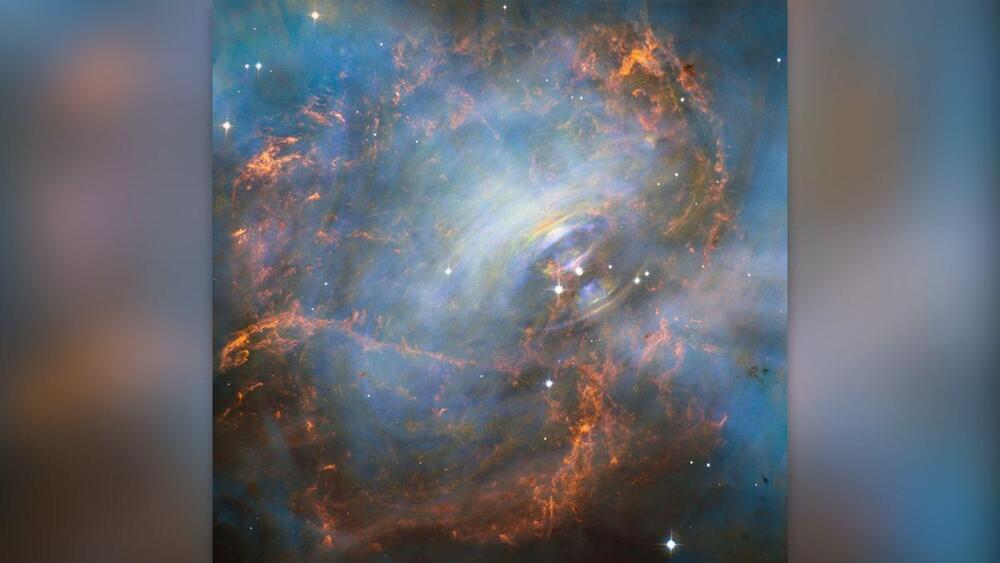

In the extreme hearts of neutron stars, fundamental particles are twisted into strange ‘pasta’ shapes that could reveal untold secrets about how dead stars evolve.

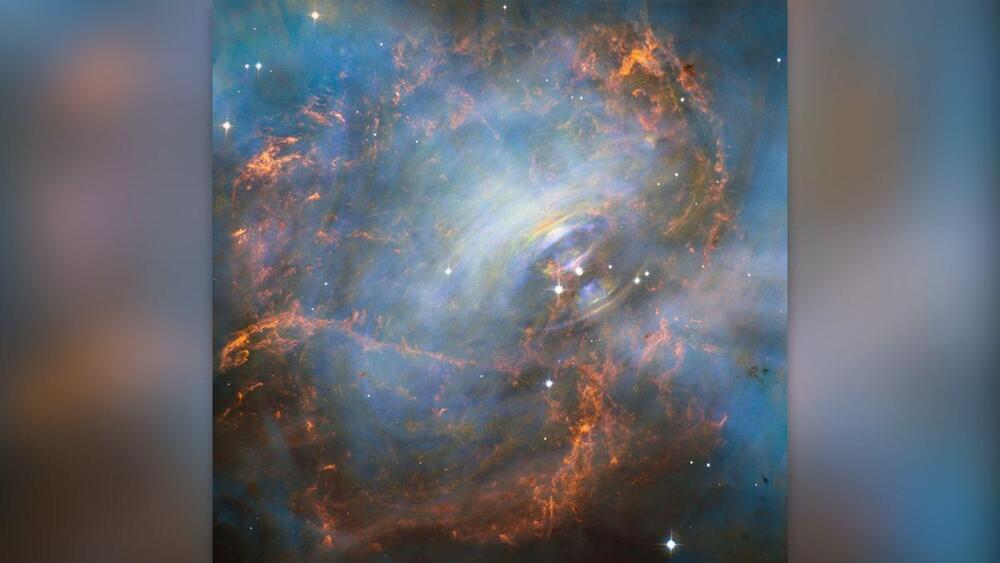

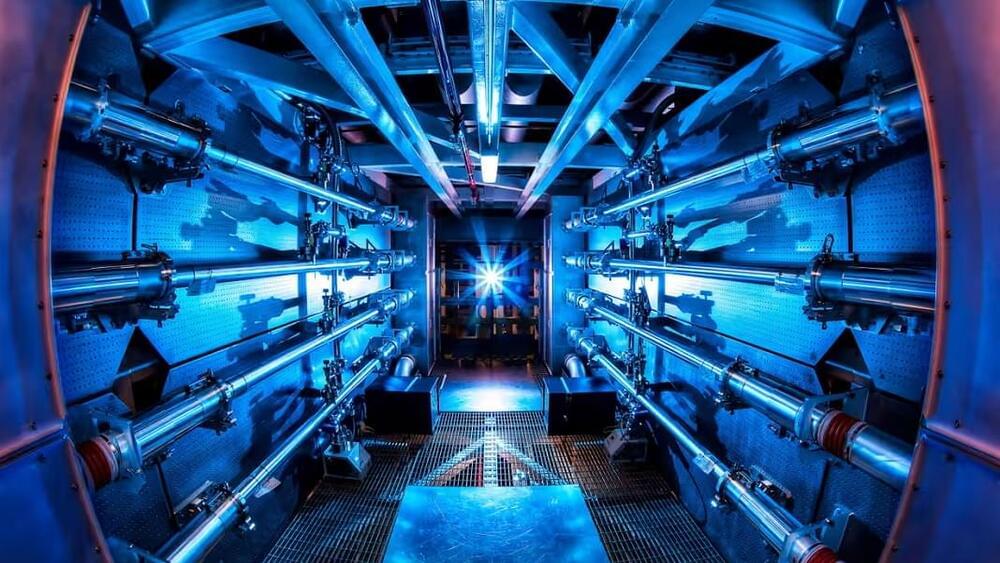

Fusion power has long been seen as a pipe dream, but in recent years the technology has appeared to be edging closer to reality. The second demonstration of a fusion reaction that creates more power than it uses is another important marker suggesting fusion’s time may be coming.

Generating power by smashing together atoms holds considerable promise, because the fuel is abundant, required in tiny amounts, and the reactions produce little long-lived radioactive waste and no carbon emissions. The problem is that initiating fusion typically uses much more energy than the reaction generates, making a commercial fusion plant a distant dream at present.

Last December though, scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory made a major breakthrough when they achieved “fusion ignition” for the first time. The term refers to a fusion reaction that produces more energy than was put in and becomes self-sustaining.

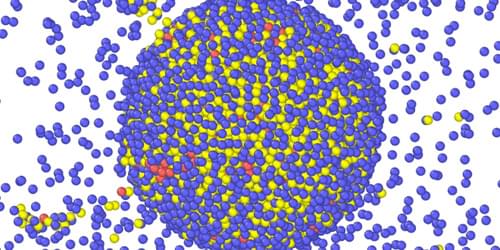

Many biological processes depend on chemical reactions that are localized in space and time and therefore require catalytic components that self-organize. The collective behavior of these active particles depends on their chemotactic movement—how they sense and respond to chemical gradients in the environment. Mixtures of such active catalysts generate complex reaction networks, and the process by which self-organization emerges in these networks presents a puzzle. Jaime Agudo-Canalejo of the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization, Germany, and his colleagues now show that the phenomenon of self-organization depends strongly on the network topology [1]. The finding provides new insights for understanding microbiological systems and for engineering synthetic catalytic colloids.

In a biological metabolic network, catalysts convert substrates into products. The product of one catalyst species acts as the substrate for another species—and so on. Agudo-Canalejo and his team modeled a three-species system. First, building on a well-established continuum theory for catalytically active species that diffuse along chemical gradients, they showed that systems where each species responds chemotactically only to its own substrate cannot self-organize unless one species is self-attracting. Next, they developed a model that allowed species to respond to both their substrates and their products. Pair interactions between different species in this more complex model drove an instability that spread throughout the three-species system, causing the catalysts to clump together. Surprisingly, this self-organization process occurred even among particles that were individually self-repelling.

The researchers say that their discovery of the importance of network topology—which catalyst species affect and are affected by which substrates and products—could open new directions in studies of active matter, informing both origin-of-life research and the design of shape-shifting functional structures.

X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) first came into existence two decades ago. They have since enabled pioneering experiments that “see” both the ultrafast and the ultrasmall. Existing devices typically generate short and intense x-ray pulses at a rate of around 100 x-ray pulses per second. But one of these facilities, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, is set to eclipse this pulse rate. The LCLS Collaboration has now announced “first light” for its upgraded machine, LCLS-II. When it is fully up and running, LCLS-II is expected to fire one million pulses per second, making it the world’s most powerful x-ray laser.

The LCLS-II upgrade signifies a quantum leap in the machine’s potential for discovery, says Robert Schoenlein, the LCLS’s deputy director for science. Now, rather than “demonstration” experiments on simple, model systems, scientists will be able to explore complex, real-world systems, he adds. For example, experimenters could peer into biological systems at ambient temperatures and physiological conditions, study photochemical systems and catalysts under the conditions in which they operate, and monitor nanoscale fluctuations of the electronic and magnetic correlations thought to govern the behavior of quantum materials.

The XFEL was first proposed in 1992 to tackle the challenge of building an x-ray laser. Conventional laser schemes excite large numbers of atoms into states from which they emit light. But excited states with energies corresponding to x-ray wavelengths are too short-lived to build up a sizeable excited-state population. XFELs instead rely on electrons traveling at relativistic speed through a periodic magnetic array called an undulator. Moving in a bunch, the electrons wiggle through the undulator, emitting x-ray radiation that interacts multiple times with the bunch and becomes amplified. The result is a bright x-ray beam with laser coherence.

The 2022 eruption of a partially submerged volcano near Tonga produced ejecta that hurtled at 122 kilometers per hour—as determined by timing the ensuing rupture of a seafloor cable.

On January 15, 2022, Earth experienced its most explosive volcanic eruption in 140 years at Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai, a partially submerged volcano in the Pacific Ocean near the Kingdom of Tonga’s main island. Now Michael Clare and Isobel Yeo of the UK’s National Oceanography Centre and their colleagues have determined the maximum speed of the underwater rock flows associated with this event [1]. Their study constitutes the most detailed investigation into the underwater aftermath of a powerful volcanic eruption and opens a new window onto a broad class of particle-laden flows.

The eruption at Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai hurled more than 6 km3 of debris up to a height of 57 km. When that ejecta plunged back to Earth, some of it struck the volcano’s steep underwater slopes, launching torrents of water-entrained sediment outward across the seafloor. Seven minutes after the initial eruption, Tonga lost its internet connection to the rest of the world, an event that Clare, Yeo, and their colleagues used to deduce the speed at which the entrained material moved.

Engineering researchers at Lehigh University have discovered that sand can actually flow uphill.

The team’s findings were published today in the journal Nature Communications. A corresponding video shows what happens when torque and an attractive force is applied to each grain—the grains flow uphill, up walls, and up and down stairs.

“After using equations that describe the flow of granular materials,” says James Gilchrist, the Ruth H. and Sam Madrid Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in Lehigh’s P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science and one of the authors of the paper, “we were able to conclusively show that these particles were indeed moving like a granular material, except they were flowing uphill.”

Astronomers say they have spotted evidence of stars fuelled by the annihilation of dark matter particles. If true, it could solve the cosmic mystery of how supermassive black holes appeared so early.

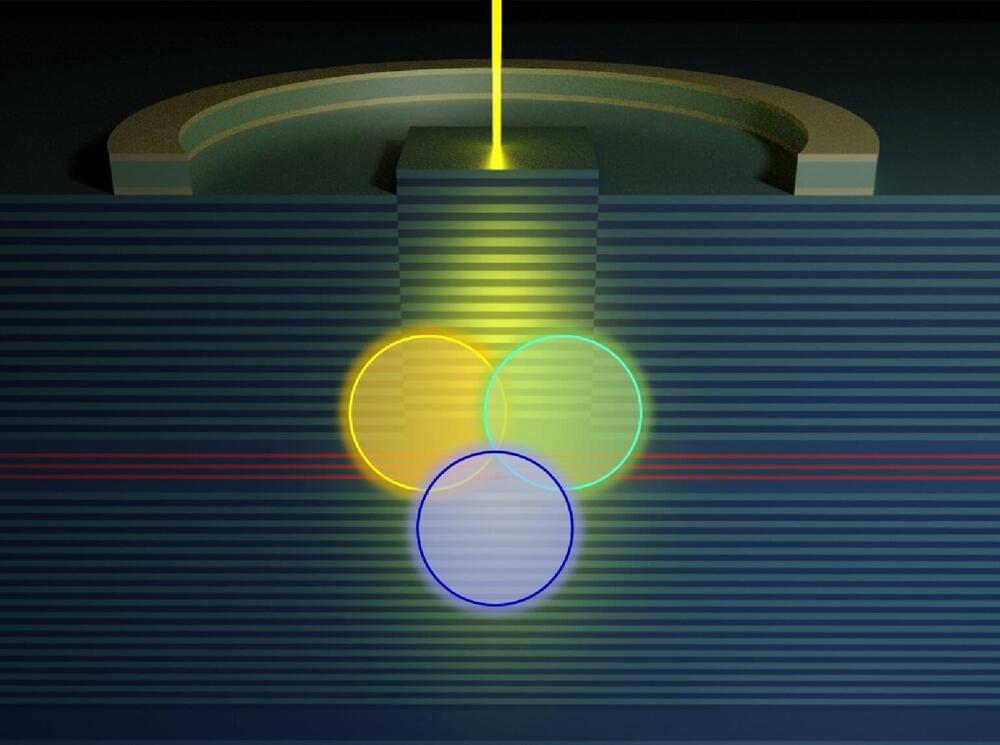

In a paper published today (Sept. 18) in Nature Communications, researchers from the Paul-Drude-Institut in Berlin, Germany, and the Instituto Balseiro in Bariloche, Argentina, demonstrated that the mixing of confined quantum fluids of light and GHz sound leads to the emergence of an elusive phonoriton quasi-particle—in part a quantum of light (photon), a quantum of sound (phonon) and a semiconductor exciton. This discovery opens a novel way to coherently convert information between optical and microwave domains, bringing potential benefits to the fields of photonics, optomechanics and optical communication technologies.

The research team’s work draws inspiration from an everyday phenomenon: the transfer of energy between two coupled oscillators, such as, for instance, two pendulums connected by a spring. Under specific coupling conditions, known as the strong-coupling (SC) regime, energy continuously oscillates between the two pendulums, which are no longer independent, as their frequencies and decay rates are not those of the uncoupled ones. The oscillators can also be photonic or electronic quantum states: the SC regime, in this case, is fundamental for quantum state control and swapping.

In the above example, the two pendulums are assumed to have the same frequency, i.e., in resonance. However, hybrid quantum systems require coherent information transfer between oscillators with largely dissimilar frequencies. Here, one important example is in networks of quantum computers. While the most promising quantum computers operate with microwave qubits (i.e., at few GHz), quantum information is efficiently transferred using near infrared photons (100ds THz).