These theoretical particles ignore the basic structure of cause and effect, leading to some pretty absurd situations.

Femtotech: Computing at the femtometer scale using quarks and gluons.

How the properties of quarks and gluons can be used (in principle) to perform computation at the femtometer (10^−15 meter) scale.

I’ve been thinking on and off for two decades about the possibility of a femtotech. Now that nanotech is well established, and well funded, I feel that the time is right to start thinking about the possibility of a femtotech.

You may ask, “What about picotech?” — technology at the picometer (10-12m) scale. The simple answer to this question is that nature provides nothing at the picometer scale. An atom is about 10–10 m in size.

The next smallest thing in nature is the nucleus, which is about 100,000 times smaller, i.e., 10–15 m in size — a femtometer, or “fermi.” A nucleus is composed of protons and neutrons (i.e., “nucleons”), which we now know are composed of 3 quarks, which are bound (“glued”) together by massless (photon-like) particles called “gluons.”

Hence if one wanted to start thinking about a possible femtotech, one would probably need to start looking at how quarks and gluons behave, and see if these behaviors might be manipulated in such a way as to create a technology, i.e., computation and engineering (building stuff).

In this essay, I concentrate on the computation side, since my background is in computer science. Before I started ARCing (After Retirement Careering), I was a computer science professor who gave himself zero chance of getting a grant from conservative NSF or military funders in the U.S. to speculate on the possibilities of a femtotech. But now that I’m no longer a “wager,” I’m free to do what I like, and can join the billion strong “army” of ARCers, to pursue my own passions.

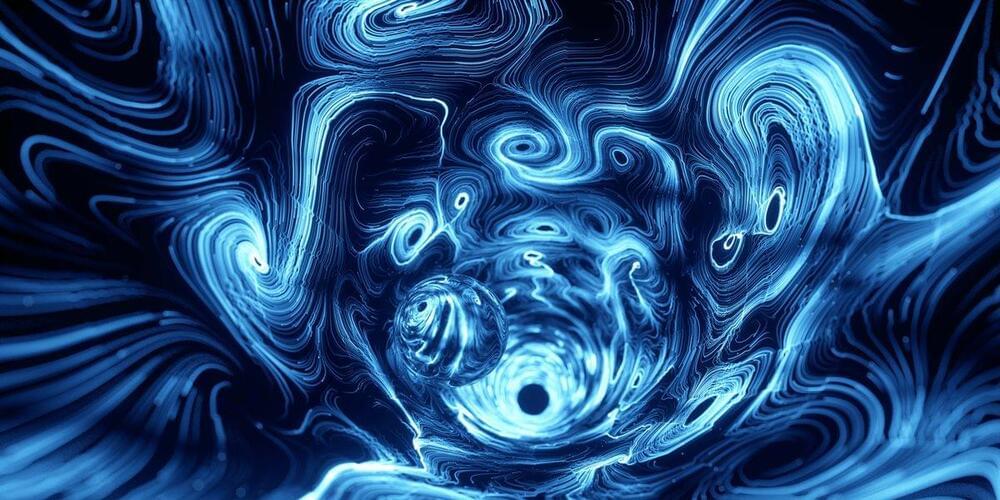

Researchers have created chip-based photonic resonators that operate in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible regions of the spectrum and exhibit a record low UV light loss. The new resonators lay the groundwork for increasing the size, complexity and fidelity of UV photonic integrated circuit (PIC) design, which could enable new miniature chip-based devices for applications such as spectroscopic sensing, underwater communication and quantum information processing.

“Compared to the better-established fields like telecom photonics and visible photonics, UV photonics is less explored even though UV wavelengths are needed to access certain atomic transitions in atom/ion-based quantum computing and to excite certain fluorescent molecules for biochemical sensing,” said research team member Chengxing He from Yale University. “Our work sets a good basis toward building photonic circuits that operate at UV wavelengths.”

In Optics Express, the researchers describe the alumina-based optical microresonators and how they achieved an unprecedented low loss at UV wavelengths by combining the right material with optimized design and fabrication.

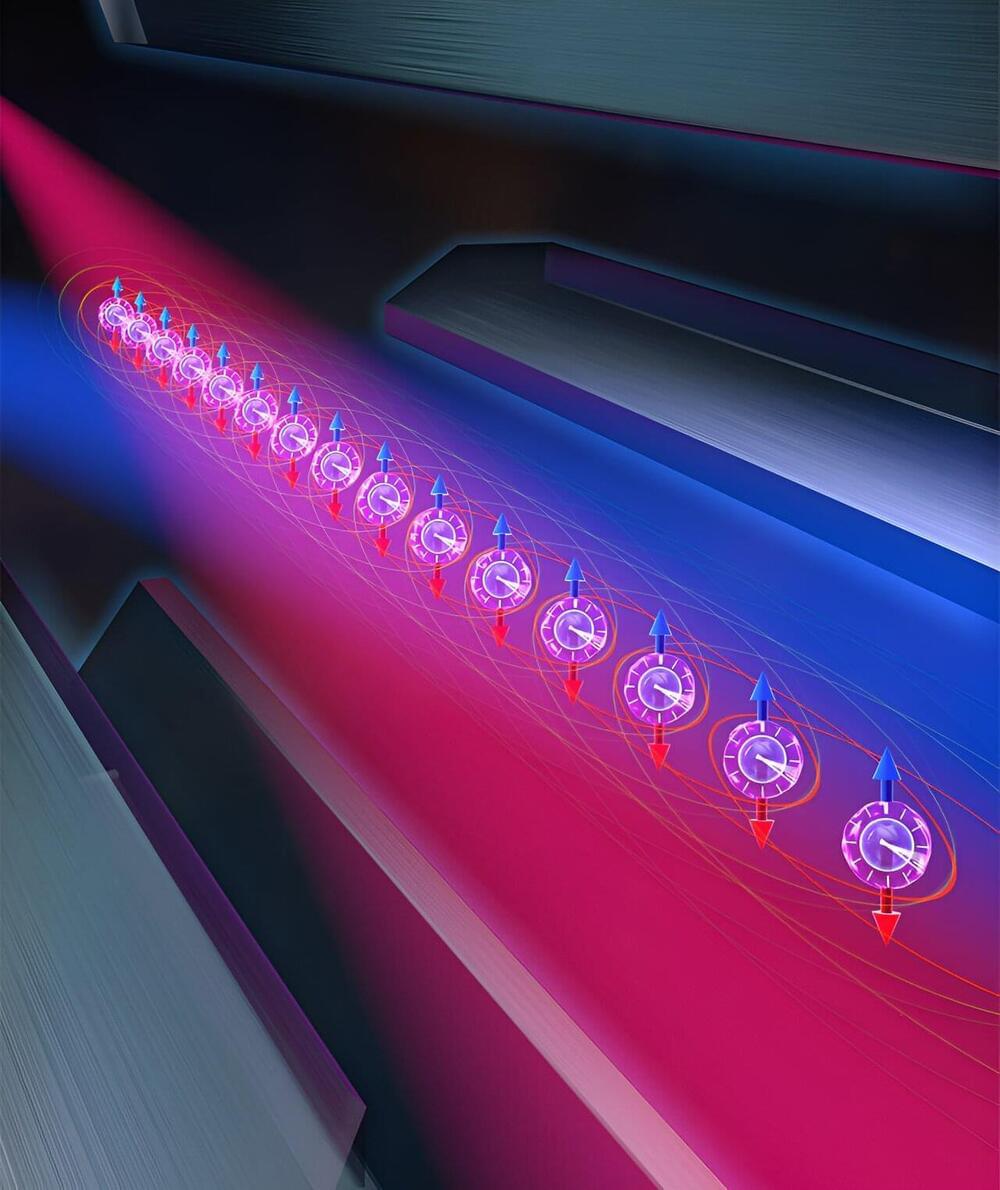

Opening new possibilities for quantum sensors, atomic clocks and tests of fundamental physics, JILA researchers have developed new ways of “entangling” or interlinking the properties of large numbers of particles. In the process they have devised ways to measure large groups of atoms more accurately even in disruptive, noisy environments.

The new techniques are described in a pair of papers published in Nature. JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Entanglement is the holy grail of measurement science,” said Ana Maria Rey, a theoretical physicist and a JILA and NIST Fellow. “Atoms are the best sensors ever. They’re universal. The problem is that they’re quantum objects, so they’re intrinsically noisy. When you measure them, sometimes they’re in one energy state, sometimes they’re in another state. When you entangle them, you can manage to cancel the noise.”

Chinese researchers are working on ways to develop their own semiconductor lithography process to compete with ASML.

Researchers at Tsinghua University are working to bring microchip production to China to bypass US sanctions, reports the South China Morning Post.

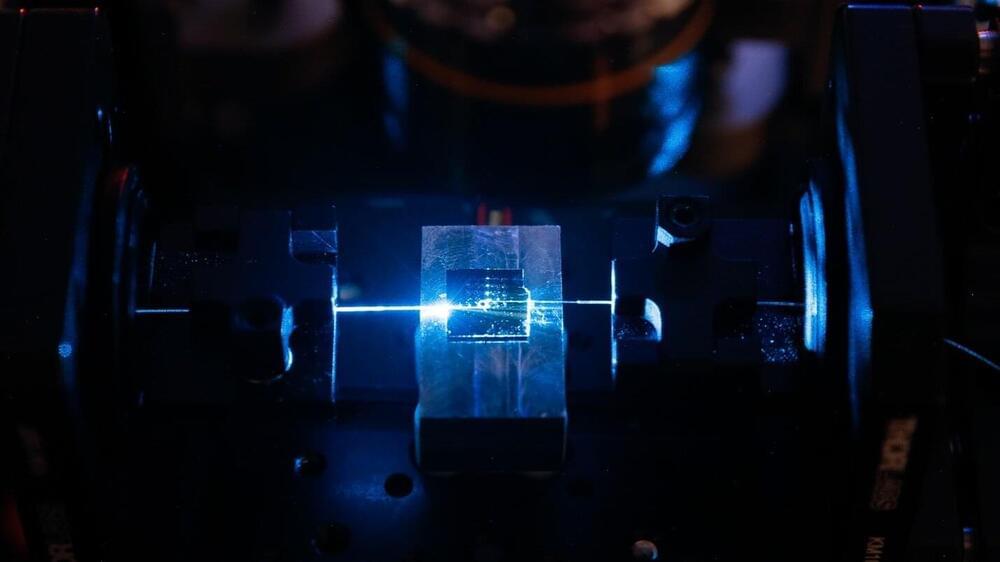

Using a new method called steady-state microbunching (SSMB), the team believes this new technique could be employed to mass produce high-quality microchips and reduce China’s dependence on lithography systems from the likes of industry giants like Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography (ASML).

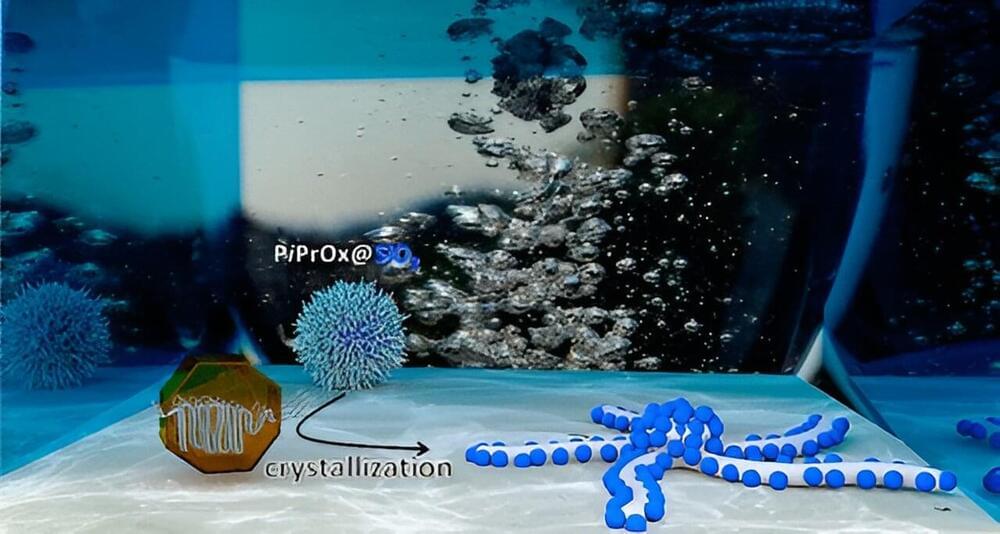

Scientists from the Friedrich Schiller University Jena and the Friedrich Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, both Germany, have successfully developed nanomaterials using a so-called bottom-up approach. As reported in the journal ACS Nano, they exploit the fact that crystals often grow in a specific direction during crystallization. These resulting nanostructures could be used in various technological applications.

“Our structures could be described as worm-like rods with decorations,” explains Prof. Felix Schacher. “Embedded in these rods are spherical nanoparticles; in our case, this was silica. However, instead of silica, conductive nanoparticles or semiconductors could also be used—or even mixtures, which can be selectively distributed in the nanocrystals using our method,” he adds. Accordingly, the range of possible applications in science and technology is broad, spanning from information processing to catalysis.

“The primary focus of this work was to understand the preparation method as such,” explains the chemist. To produce nanostructures, he elaborates, there are two different approaches: larger particles are ground down to nanometer size, or the structures are built up from smaller components.

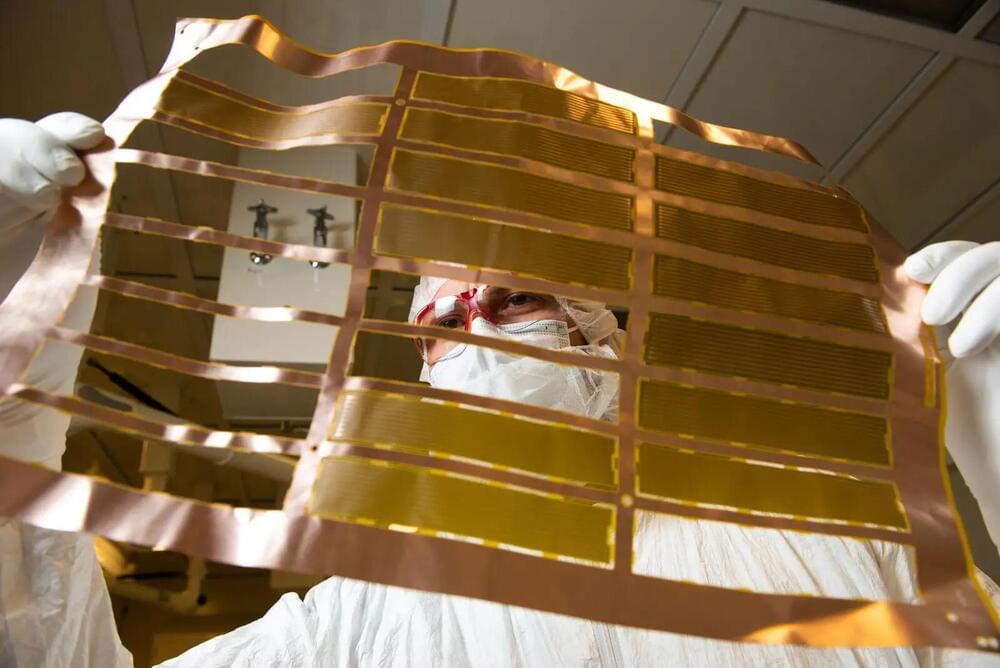

Imagine trying to tune a radio to a single station but instead encountering static noise and interfering signals from your own equipment. That is the challenge facing research teams searching for evidence of extremely rare events that could help understand the origin and nature of matter in the universe. It turns out that when you are trying to tune into some of the universe’s weakest signals, it helps to make your instruments very quiet.

Around the world, more than a dozen teams are listening for the pops and electronic sizzle that might mean they have finally tuned into the right channel. These scientists and engineers have gone to extraordinary lengths to shield their experiments from false signals created by cosmic radiation. Most such experiments are found in very inaccessible places—such as a mile underground in a nickel mine in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, or in an abandoned gold mine in Lead, South Dakota—to shield them from naturally radioactive elements on Earth. However, one such source of fake signals comes from natural radioactivity in the very electronics that are designed to record potential signals.

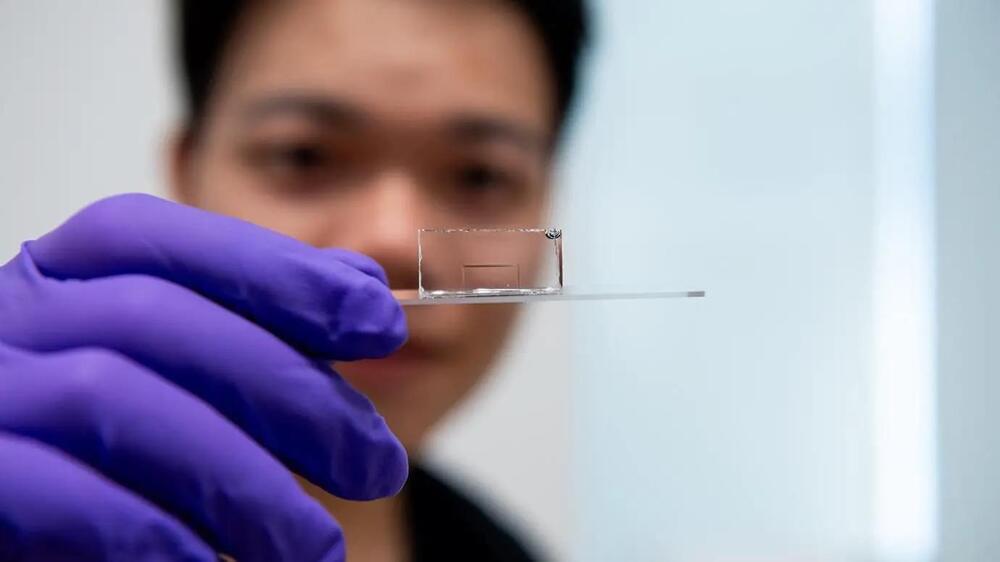

Channeling light from one location to another is the backbone of our modern world. Across deep oceans and vast continents, fiber optic cables transport light containing data ranging from YouTube clips to banking transmissions—all within fibers as thin as a strand of hair.

University of Chicago Prof. Jiwoong Park, however, wondered what would happen if you made even thinner and flatter strands—in effect, so thin that they’re actually 2D instead of 3D. What would happen to the light?

Through a series of innovative experiments, he and his team found that a sheet of glass crystal just a few atoms thick could trap and carry light. Not only that, but it was surprisingly efficient and could travel relatively long distances—up to a centimeter, which is very far in the world of light-based computing.

Peter Atkins, James Ladyman, and Joanna Kavenna argue over the existence of physical reality.

Watch the full debate at https://iai.tv/video/the-world-that-disappeared?utm_source=Y…escription.

No-one who has ever stepped on a Lego brick could doubt the reality of physical objects. Yet from Heraclitus to George Berkeley, many philosophers claimed to have disproven the existence of things. Now even high-energy particle physicists are inclined to agree and describe material stuff as energy, or even as mathematical constructs. Could the world truly be made up of fields and processes, rather than physical stuff? Or is science trapped in a philosophical fantasy from which it needs to escape?

#PhysicalRealityDebate #MaterialistWorld.

#RelatingToReality.

Chemist and Fellow of Lincoln College Peter Atkins, Philosopher of Science at the University of Bristol James Ladyman and author of A Field Guide to Reality Joanna Kavenna debate whether the everyday objects that surround us are an illusion. Julian Baggini hosts.

To discover more talks, debates, interviews and academies with the world’s leading speakers visit https://iai.tv/subscribe?utm_source=YouTube&utm_medium=descr…sappeared.

Astronomers say they have spotted evidence of stars fuelled by the annihilation of dark matter particles. If true, it could solve the cosmic mystery of how supermassive black holes appeared so early.