BBC News

The elusive substance holds the key to discovering how the Universe was formed.

Gravitational acceleration of anti-matter is close to that of matter on Earth and scientists are now working to measure it accurately.

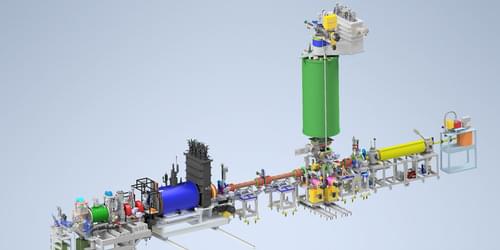

Experiments conducted by the Antihydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus (ALPHA) collaboration at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland, have shown that antihydrogen particles, too are pulled downward by gravity and do not levitate as some physicists suggest a press release said.

Antihydrogen is the simplest antimatter particle that we know exists. The opposite of hydrogen contains antimatter components such as an antiproton, a negatively charged proton, and a positron, a positively charged electron.

The LHC is back delivering collisions to the experiments after the successful leak repair in August. But instead of protons, it is now the turn of lead ion beams to collide, marking the first heavy-ion run in 5 years. Compared to previous runs, the lead nuclei will be colliding with an increased energy of 5.36 TeV per nucleon pair (compared to 5.02 TeV previously) and the collision rate has increased by a factor of 10. The primary physics goal of this run is the study of the elusive state of matter known as quark-gluon plasma, that is believed to have filled the Universe up to a millionth of a second after the Big Bang and can be recreated in the laboratory in heavy-ion collisions.

Quark-gluon plasma is a state of matter made of free quarks (particles that make up hadrons such as the proton and the neutron) and gluons (carriers of the strong interaction, which hold the quarks together inside the hadrons). In all but the most extreme conditions, quarks cannot exist individually and are bound inside hadrons. In heavy-ion collisions however, hundreds of protons and neutrons collide, forming a system with such density and temperature that the colliding nuclei melt together, and a tiny fireball of quark-gluon plasma forms, the hottest substance known to exist. Inside this fireball quarks and gluons can move around freely for a split-second, until the plasma expands and cools down, turning back into hadrons.

The ongoing heavy-ion run is expected to bring significant advances in our understanding of quark-gluon plasma. In addition to the improved parameters of the lead-ion beams, significant upgrades have been performed in the experiments that detect and analyse the collisions. ALICE, the experiment which primarily focuses on studies of quark-gluon plasma, is now using an entirely new mode of data processing storing all collisions without selection, resulting in up to 100 times more collisions being recorded per second. In addition, its track reconstruction efficiency and precision have increased due to the installation of new subsystems and upgrades of existing ones. CMS and ATLAS have also upgraded their data acquisition, reconstruction and selection infrastructure to take advantage of the increased collision rates. ATLAS has installed improved Zero Degree Calorimeters, which are critical in event selection and provide new measurement capabilities.

The 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics goes to John Cardy and Alexander Zamolodchikov for their work in applying field theory to diverse problems.

Many physicists hear the words “quantum field theory,” and their thoughts turn to electrons, quarks, and Higgs bosons. In fact, the mathematics of quantum fields has been used extensively in other domains outside of particle physics for the past 40 years. The 2024 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics has been awarded to two theorists who were instrumental in repurposing quantum field theory for condensed-matter, statistical physics, and gravitational studies.

“I really want to stress that quantum field theory is not the preserve of particle physics,” says John Cardy, a professor emeritus from the University of Oxford. He shares the Breakthrough Prize with Alexander Zamolodchikov from Stony Brook University, New York.

A complete quantum computing system could be as large as a two-car garage when one factors in all the paraphernalia required for smooth operation. But the entire processing unit, made of qubits, would barely cover the tip of your finger.

Today’s smartphones, laptops and supercomputers contain billions of tiny electronic processing elements called transistors that are either switched on or off, signifying a 1 or 0, the binary language computers use to express and calculate all information. Qubits are essentially quantum transistors. They can exist in two well-defined states—say, up and down—which represent the 1 and 0. But they can also occupy both of those states at the same time, which adds to their computing prowess. And two—or more—qubits can be entangled, a strange quantum phenomenon where particles’ states correlate even if the particles lie across the universe from each other. This ability completely changes how computations can be carried out, and it is part of what makes quantum computers so powerful, says Nathalie de Leon, a quantum physicist at Princeton University. Furthermore, simply observing a qubit can change its behavior, a feature that de Leon says might create even more of a quantum benefit. “Qubits are pretty strange. But we can exploit that strangeness to develop new kinds of algorithms that do things classical computers can’t do,” she says.

Scientists are trying a variety of materials to make qubits. They range from nanosized crystals to defects in diamond to particles that are their own antiparticles. Each comes with pros and cons. “It’s too early to call which one is the best,” says Marina Radulaski of the University of California, Davis. De Leon agrees. Let’s take a look.

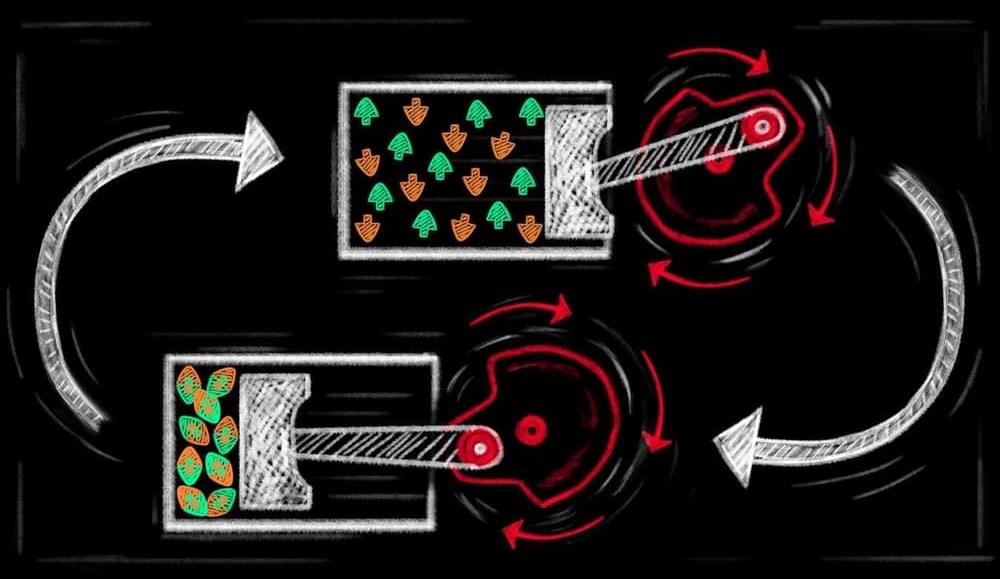

A quantum engine that works by toggling the properties of an ultracold atom cloud could one day be used to charge quantum batteries.

Founded in 2021, Virginia-based Procyon Photonics is a startup aiming to change the future of computing hardware with its focus on optical computing. What makes the company unique is that their entire team consists of current high school students, and its co-founder, CEO, and CTO, Sathvik Redrouthu, holds the distinction of being the world’s youngest CEO in the photonic and optical computing sector.

Optical computing represents an innovative leap from traditional computing, which relies on electrons moving through wires and transistors. Instead, this relatively nascent field seeks to harness photons — particles of light — as the fundamental elements in computational processes. The promise of optical computing is compelling enough that industry giants like IBM and Microsoft, among others, are heavily investing in its research and development.

Procyon is attempting to differentiate itself in this competitive landscape not just by its youth, but with their technology. The team is pioneering a unique, industry-leading optical chip, and has published a conference paper detailing how a specialized form of matrix algebra could be executed on an optoelectronic chip.

Is there an 8-dimensional “engine” behind our universe? Join Marion Kerr on a fun, visually exciting journey as she explores a mysterious, highly complex structure known simply as ‘E8’–a weird, 8-dimensional mathematical object that for some, strange reason, appears to encode all of the particles and forces of our 3-dimensional universe.

Meet surfer and renowned theoretical physicist Garrett Lisi as he rides the waves and paraglides over the beautiful Hawaiian island of Maui and talks about his groundbreaking discovery about E8 relates deeply to our reality; and learn why Los Angeles based Klee Irwin and his group of research scientists believe that the universe is essentially a 3-dimensional “shadow” of this enigmatic… thing… that may exist behind the curtain of our reality.

ENJOY THE MOVIE! and SHARE IT!

Main film credits:

Host: Marion Kerr.

Written, Directed and Edited by David Jakubovic.

Director of Photography: Natt McFee.

Lead animator: Sarah Winters.

Original Music by Daniel Jakubovic.

Rerecording mixer: Patrick Giraudi.

Line Producer: Piper Norwood.

Executive producer: Klee Irwin.

Producers: David Jakubovic, Stephanie Nadanarajah.

Also starring Daniel Jakubovic as Agent Smooth.

VISIT THE QGR WEBSITE: http://www.quantumgravityresearch.org.