To be clear, humans are not the pinnacle of evolution. We are confronted with difficult choices and cannot sustain our current trajectory. No rational person can expect the human population to continue its parabolic growth of the last 200 years, along with an ever-increasing rate of natural resource extraction. This is socio-economically unsustainable. While space colonization might offer temporary relief, it won’t resolve the underlying issues. If we are to preserve our blue planet and ensure the survival and flourishing of our human-machine civilization, humans must merge with synthetic intelligence, transcend our biological limitations, and eventually evolve into superintelligent beings, independent of material substrates—advanced informational beings, or ‘infomorphs.’ In time, we will shed the human condition and upload humanity into a meticulously engineered inner cosmos of our own creation.

Much like the origin of the Universe, the nature of consciousness may appear to be a philosophical enigma that remains perpetually elusive within the current scientific paradigm. However, I emphasize the term “current.” These issues are not beyond the reach of alternative investigative methods, ones that the next scientific paradigm will inevitably incorporate with the arrival of Artificial Superintelligence.

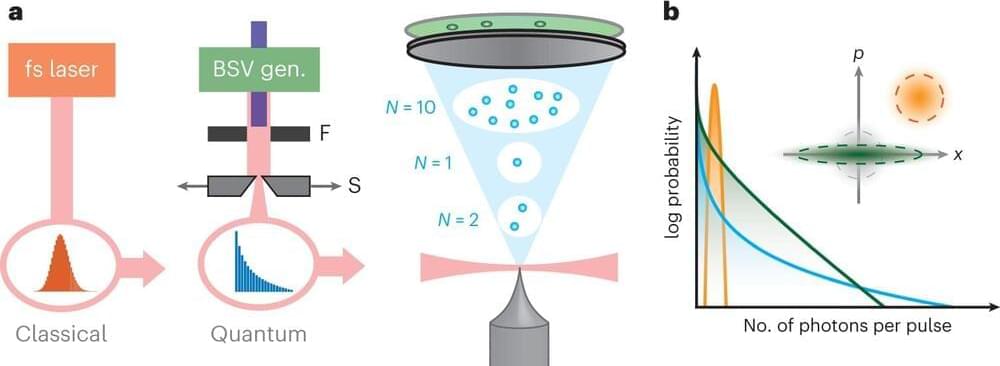

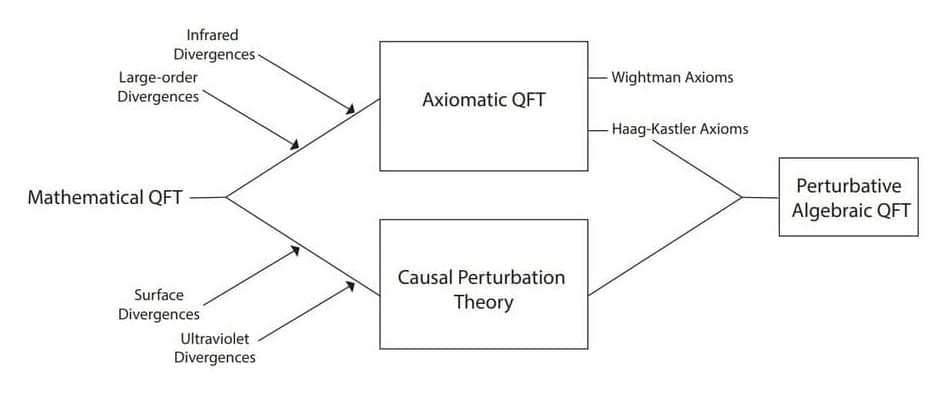

The era of traditional, human-centric theoretical modeling and problem-solving—developing hypotheses, uncovering principles, and validating them through deduction, logic, and repeatable experimentation—may be nearing the end. A confluence of factors—Big Data, algorithms, and computational resources—are steering us towards a new type of discovery, one that transcends the limitations of human-like logic and decision-making— the one driven solely by AI superintelligence, nestled in quantum neo-empiricism and a fluidity of solutions. These novel scientific methodologies may encompass, but are not limited to, computing supercomplex abstractions, creating simulated realities, and manipulating matter-energy and the space-time continuum itself.