Learn more about quantum mechanics from my course on Brilliant! First 30 days are free and 20% off the annual premium subscription when you use our link ➜ https://brilliant.org/sabine.

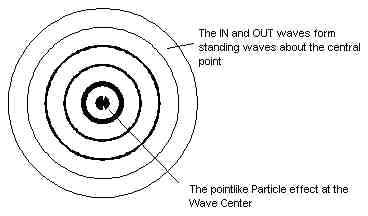

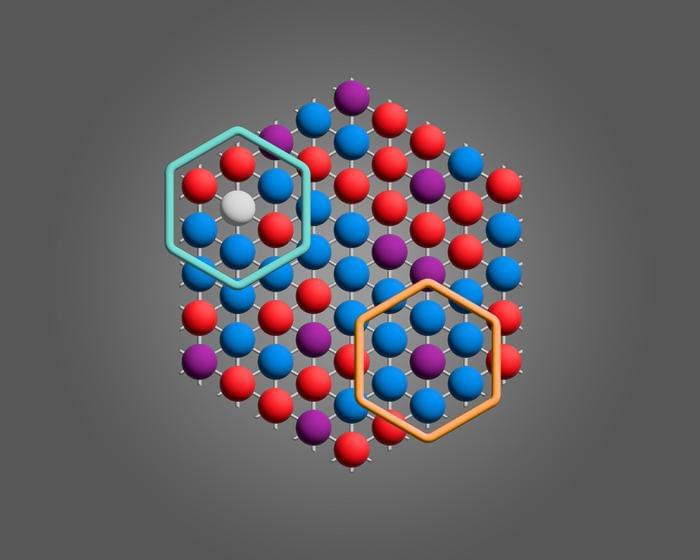

Particle physics have conducted a test using data from the Large Hadron Collider at CERN to see if the particles in their collisions play by the rules of quantum physics — whether they have quantum entanglement. Why was this test conducted when previous tests already found that entanglement is real? Is it just nonsense or is it not nonsense? Let’s have a look.

Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.

🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/

💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle…

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

🖼️ On instagram ➜ / sciencewtg.

#science #sciencenews #CERN #physics