Dr. Brian A. Grierson, Ph.D. is a leading physicist and engineer in magnetic fusion energy and is currently Director of Fusion Energy Technologies at General…

Category: nuclear energy – Page 7

Researchers discover a hidden atomic order that persists in metals even after extreme processing

For decades, it’s been known that subtle chemical patterns exist in metal alloys, but researchers thought they were too minor to matter—or that they got erased during manufacturing. However, recent studies have shown that in laboratory settings, these patterns can change a metal’s properties, including its mechanical strength, durability, heat capacity, radiation tolerance, and more.

Now, researchers at MIT have found that these chemical patterns also exist in conventionally manufactured metals. The surprising finding revealed a new physical phenomenon that explains the persistent patterns.

In a paper published in Nature Communications today, the researchers describe how they tracked the patterns and discovered the physics that explains them. The authors also developed a simple model to predict chemical patterns in metals, and they show how engineers could use the model to tune the effect of such patterns on metallic properties, for use in aerospace, semiconductors, nuclear reactors, and more.

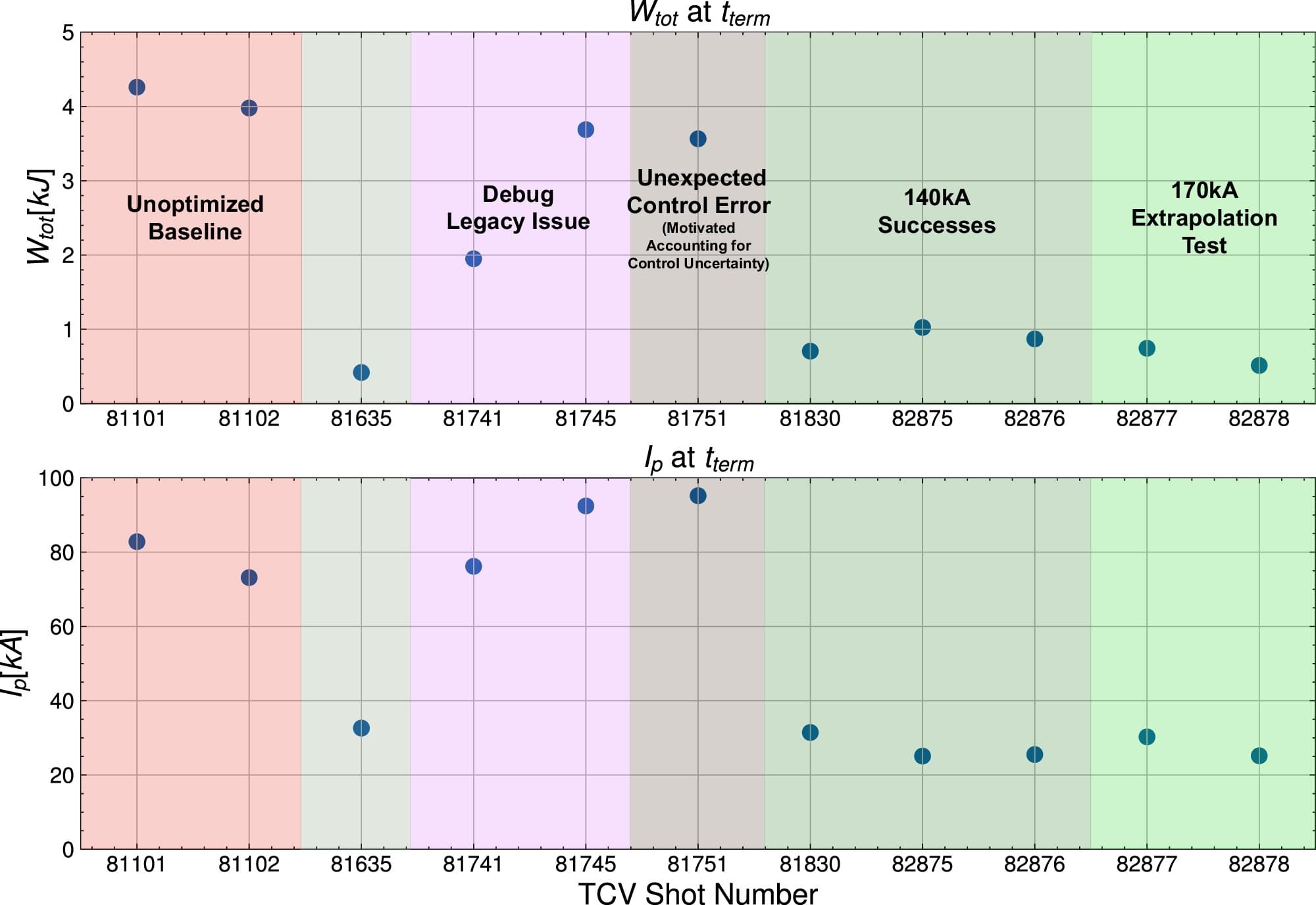

Plasma rampdown prediction model could improve reliability of fusion power plants

Tokamaks are machines that are meant to hold and harness the power of the sun. These fusion machines use powerful magnets to contain a plasma hotter than the sun’s core and push the plasma’s atoms to fuse and release energy. If tokamaks can operate safely and efficiently, the machines could one day provide clean and limitless fusion energy.

Today, there are a number of experimental tokamaks in operation around the world, with more underway. Most are small-scale research machines built to investigate how the devices can spin up plasma and harness its energy.

One of the challenges that tokamaks face is how to safely and reliably turn off a plasma current that is circulating at speeds of up to 100 kilometers per second, at temperatures of over 100 million degrees Celsius.

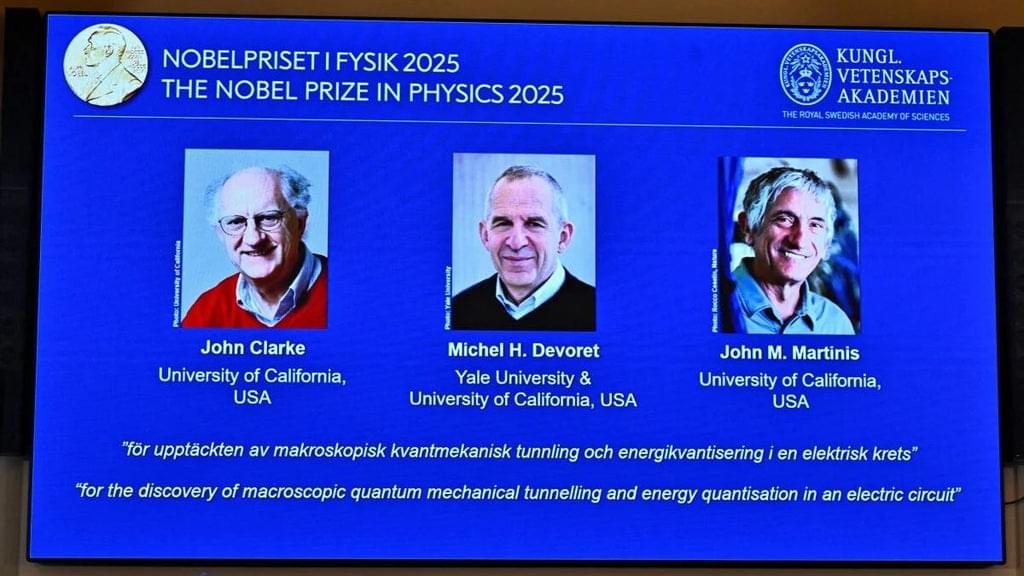

2025 Nobel Prize in Physics Peer Review

Introduction.

Grounded in the scientific method, it critically examines the work’s methodology, empirical validity, broader implications, and opportunities for advancement, aiming to foster deeper understanding and iterative progress in quantum technologies. ## Executive Summary.

This work, based on experiments conducted in 1984–1985, addresses a fundamental question in quantum physics: the scale at which quantum effects persist in macroscopic systems.

By engineering a Josephson junction-based circuit where billions of Cooper pairs behave collectively as a single quantum entity, the laureates provided empirical evidence that quantum phenomena like tunneling through energy barriers and discrete energy levels can manifest in human-scale devices.

This breakthrough bridges microscopic quantum mechanics with macroscopic engineering, laying foundational groundwork for advancements in quantum technologies such as quantum computing, cryptography, and sensors.

Overall strengths include rigorous experimental validation and profound implications for quantum information science, though gaps exist in scalability to room-temperature applications and full mitigation of environmental decoherence.

Framed within the broader context, this award highlights the enduring evolution of quantum mechanics from theoretical curiosity to practical innovation, building on prior Nobel-recognized discoveries like the Josephson effect (1973) and superconductivity mechanisms (1972).

Virtual particles: How physicists’ clever bookkeeping trick could underlie reality

A clever mathematical tool known as virtual particles unlocks the strange and mysterious inner workings of subatomic particles. What happens to these particles within atoms would stay unexplained without this tool. The calculations using virtual particles predict the bizarre behavior of subatomic particles with such uncanny accuracy that some scientists think “they must really exist.”

Virtual particles are not real—it says so right in their name—but if you want to understand how real particles interact with each other, they are unavoidable. They are essential tools to describe three of the forces found in nature: electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces.

Real particles are lumps of energy that can be “seen” or detected by appropriate instruments; this feature is what makes them observable, or real. Virtual particles, on the other hand, are a sophisticated mathematical tool and cannot be seen. Physicist Richard Feynman invented them to describe the interactions between real particles.

Meet Irene Curie, the Nobel-winning atomic physicist who changed the course of modern cancer treatment

The adage goes “like mother like daughter,” and in the case of Irene Joliot-Curie, truer words were never spoken. She was the daughter of two Nobel Prize laureates, Marie Curie and Pierre Curie, and was herself awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1935 together with her husband, Frederic Joliot.

While her parents received the prize for the discovery of natural radioactivity, Irene’s prize was for the synthesis of artificial radioactivity. This discovery changed many fields of science and many aspects of our everyday lives. Artificial radioactivity is used today in medicine, agriculture, energy production, food sterilization, industrial quality control and more.

We are two nuclear physicists who perform experiments at different accelerator facilities around the world. Irene’s discovery laid the foundation for our experimental studies, which use artificial radioactivity to understand questions related to astrophysics, energy, medicine and more.

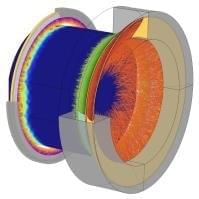

New AI enhances the view inside fusion energy systems

Imagine watching a favorite movie when suddenly the sound stops. The data representing the audio is missing. All that’s left are images. What if artificial intelligence (AI) could analyze each frame of the video and provide the audio automatically based on the pictures, reading lips and noting each time a foot hits the ground?

That’s the general concept behind a new AI that fills in missing data about plasma, the fuel of fusion, according to Azarakhsh Jalalvand of Princeton University. Jalalvand is the lead author on a paper about the AI, known as Diag2Diag, that was recently published in Nature Communications.

“We have found a way to take the data from a bunch of sensors in a system and generate a synthetic version of the data for a different kind of sensor in that system,” he said. The synthetic data aligns with real-world data and is more detailed than what an actual sensor could provide. This could increase the robustness of control while reducing the complexity and cost of future fusion systems. “Diag2Diag could also have applications in other systems such as spacecraft and robotic surgery by enhancing detail and recovering data from failing or degraded sensors, ensuring reliability in critical environments.”

Demonstration of a next-generation wavefront actuator for gravitational-wave detection

In the last decade, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the European Virgo Observatory have opened a new observational window on the universe. These cavity-enhanced laser interferometers sense spacetime strain, generated by distant astrophysical events such as black hole mergers, to an RMS fluctuation of a few parts in 1021 over a multi-kilometer baseline. Optical advancements in laser wavefront control are key to advancing the sensitivity of current detectors and enabling a planned next-generation 40 km gravitational wave observatory in the United States, known as Cosmic Explorer. We report an experimental demonstration of a wavefront control technique for gravitational-wave detection, obtained from testing a full-scale prototype on a 40 kg LIGO mirror. Our results indicate that this design can meet the unique and challenging requirements of providing higher-order precision wavefront corrections at megawatt laser power levels while introducing extremely low effective displacement noise into the interferometer. This technology will have a direct and enabling impact on the observational science, expanding the gravitational-wave detection horizon to very early times in the universe, before the first stars formed, and enabling new tests of gravity, cosmology, and dense nuclear matter.

Physics-based algorithm enables nuclear microreactors to autonomously adjust power output

A new physics-based algorithm clears a path toward nuclear microreactors that can autonomously adjust power output based on need, according to a University of Michigan-led study published in Progress in Nuclear Energy.

Easily transportable and able to generate up to 20 megawatts of thermal energy for heat or electricity, nuclear microreactors could be useful in remote locations such as rural communities, disaster zones, military bases or even cargo ships, in addition to other applications.

If integrated into an electrical grid, nuclear microreactors could provide stable, carbon-free energy, but they must be able to adjust power output to match shifting demand—a capability known as load following. In large reactors, staff make these adjustments manually, which would be cost-prohibitive in remote areas, imposing a barrier to adoption.