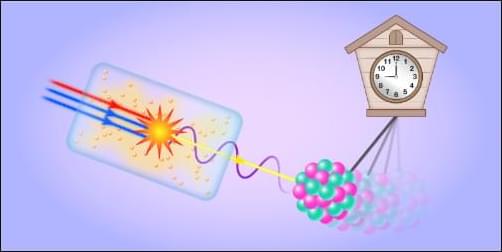

Every aspect of our world – from atomic nuclei and molecular chemistry to biology and astrophysics – emerges from the interactions of particles so small they are considered point-like. While some particles, like the electron, were discovered over a century ago, most remained hidden until the advent of modern particle accelerators. Particle physicists are dedicated to investigating the laws of nature that dictate how fundamental particles interact and combine to shape our everyday lives. By colliding particles at unprecedented energies inside massive detectors, physicists are able to create powerful magnifying lenses. Accelerators led to the discovery of W and Z bosons, carriers of the weak fundamental force, in 1983 at CERN, as well as to the discovery of the top quark, the heaviest known particle, a decade later at Fermilab (USA). These discoveries supported the experimental foundation of the Standard Model ℠ of particle physics, the theory that describes how all known fundamental particles interact. The greatest triumph of the SM came in 2012 when its last missing piece – the Higgs boson – was discovered by the ATLAS and CMS Collaborations at CERN. The SM is one of the most precisely tested scientific theories, with thousands of experimental results confirming its predictions to remarkable precision. Despite this success, the SM is not the “ultimate theory” of nature. It cannot explain experimental observations such as dark matter, an enigmatic form of matter detectable only through gravitational effects; the origin of neutrino masses, extremely light particles involved in processes like nuclear radioactive decay; nor the striking imbalance between matter and antimatter in the Universe. These unanswered questions have driven researchers to develop theoretical frameworks that go beyond the Standard Model, with many predicting the existence of additional particles and interactions. Despite intensive searches, these hypothetical particles have yet to be observed. This could mean they are too heavy (requiring collision energies beyond the reach of the LHC), that their associated new interactions are too rare to be detected in the current amount of recorded data, or that the theory is simply not borne out by nature. The focus of experimental particle physicists is, therefore, to study higher energies and collect more data, searching for any discrepancies between experimental measurements and SM predictions that could lead towards an ultimate theory of nature. Nothing is truly forbidden in the quantum world. Even “forbidden” transitions are possible so long as they follow several intermediate, rule-following steps. The Standard Model, its flavours and the search for new physics One powerful way to search for new physics phenomena is to look for processes that are expressly forbidden by the SM, occurring only via new interactions. For example, physicists often search for processes that change the properties of a fundamental particle in an unexpected way. In the SM, quarks and leptons (known as fermions) come in different “flavours”. For example, electrons and muons are both charged leptons, but they differ in mass and are therefore considered different flavours. The SM sets strict limits on how fermions can change flavour and which flavours they are allowed to transition to. While the top quark may transition into a bottom, down or strange quark through a weak interaction using the electromagnetically-charged W boson (to conserve charge overall), it is forbidden from transitioning into an up or charm quark, even through an interaction with a neutral boson such as a Z boson, gluon, photon or Higgs boson. Equivalently, while the tau lepton may produce a muon or electron through a W boson interaction (including with the associated neutrinos), it cannot produce a muon or electron through a neutral boson interaction. These rules apply to all quarks and leptons alike. Despite these rules, nothing is truly forbidden in the quantum world. Many of these transitions are physically possible so long as they follow several intermediate steps that adhere to the rules. But each additional step has a cost, reducing the overall probability of the process occurring. Thus, while these “forbidden” flavour-changing processes could occur according to the SM, they would be so rare as to never be detected by the ATLAS experiment, occurring in fewer than one in every 1,014 interactions. But what if ATLAS did detect them? Any observation of these processes would be indisputable evidence of new physics phenomena, indicating that something unknown has drastically increased the probability of these interactions. Particle physicists have even given these forbidden processes a name: those involving quarks are flavour-changing neutral currents (FCNCs), and those involving leptons are lepton flavour violation (LFV) (see Figure 1). Figure 1: The production of a top-quark pair with a subsequent FCNC decay (left) and the production of a Z boson with a subsequent LFV decay (right, where the lepton ‘l’ is an electron or a muon, but not another tau). The forbidden interactions are highlighted with red circles. The pairs of gluons (g) and quarks (q) in the initial state come from the colliding protons. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) The search for FCNC interactions in top-quark processes The LHC is the most powerful particle accelerator ever built, colliding bunches of protons every 25 nanoseconds at energies up to 13.6 TeV. Thanks to this unprecedented energy and collision rate, the LHC is often considered a particle “factory”, producing millions of top quarks and billions of Z bosons for study. That’s great news for physicists looking beyond the Standard Model, where the heavier the particle involved in the interaction, the better. Since new particles and interactions likely require large amounts of energy to manifest, they may favour a connection with the heaviest and thus most inherently energetic known particle – the top quark. Searching for FCNC processes involving the top quark is thus considered a powerful technique for uncovering new physics phenomena. In 2023, ATLAS physicists searched for FCNC interactions between a top quark and a Z boson, considering both modified production and decay mechanisms for the top quark (Figure 2). Both would generate a Z boson, a W boson and a bottom quark, with the modified decay also producing an up or charm quark. Physicists focused their search on leptonic decays of the W and Z bosons, with the W decaying to a charged lepton and a neutrino and the Z to a pair of oppositely-charged leptons of the same flavour. In practical terms, this meant looking for collision events with three charged leptons, one neutrino, one bottom quark and, in some cases, one additional up or charm quark. Figure 2: The LHC production of a single top quark via a weak interaction utilising an FCNC vertex (left), and the production of a pair of top quarks via the strong interaction, including a subsequent FCNC decay vertex (right). The FCNC vertices are highlighted with the shaded circles. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) While the ATLAS detector is very good at measuring leptons, neutrinos pass through it completely undetected. Their presence can only be inferred from the missing transverse momentum in the collision. Quarks, meanwhile, produce showers of particles in the detector’s calorimeter called jets. Top quarks almost always decay into a bottom quark, which is extremely useful for physicists. Bottom quarks combine briefly with other quarks when they are formed, and so travel farther from the collision point before they decay. The resulting b-jets they produce have unique characteristics. To identify these b-jets (a process called b-tagging) physicists use machine-learning algorithms trained to spot these characteristics. Each jet is scored based on its likelihood of originating from a b-quark. High b-tagging efficiency is crucial for finding top-quark events. However, all algorithms carry an inherent risk of misidentifying jets initiated by other quarks as b-jets. In their 2023 measurement, physicists calibrated their b-taggers to reach an efficiency of 77% for true b-jets, with a rejection factor of 5 for charm-quark-initiated jets (c-jets) and of 170 for lighter-quark-initiated jets. This means that one out of every five c-jets will be misidentified as coming from a bottom quark, and only one out of every 170 light-quark jets. If ATLAS were to observe these flavour-changing processes, it would be indisputable evidence of new physics phenomena. Figure 3: Distributions of recorded events (black points) and of simulated events (filled histograms) as a function of the Boosted Decision Tree output value. The distributions of the expected signal events, considering an FCNC coupling in single top quark production (dashed lines) or an FCNC process in the top quark decay (solid lines) are shown. The signals with an FCNC coupling between a top quark, a Z boson and an up quark (charm quark) are displayed in pink (pale blue). The lower panels show the ratio in each bin of event yields in data to the event yields from simulated background processes. A value of unity indicates that the events in data are in agreement with the predicted backgrounds. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) Physicists then defined an event selection tool to search for FCNC signatures, resulting in two signal regions (SR1 and SR2) that would be enriched in these processes. Figure 3 shows the results for the FCNC pair-produced top quarks and FCNC single-produced top quarks respectively, separated only by the number of jets required. The SM background processes resulting in similar final states are the production of a top-quark pair in association with a Z boson (see the light blue histogram in Figure 3) and the production of a pair of W/Z bosons in association with jets (see the orange histograms in Figure 3). Within each signal region, Boosted Decision Trees (BDT, a machine-learning technique) were employed to further separate the FCNC signatures from these SM backgrounds. The output of these BDTs determine the final shape of the distributions, with the aim being to push the FCNC signatures to one side of the distribution and the SM signatures to the other. This procedure was performed for FCNC processes between a top quark and an up quark (pink lines in Figure 3) and, separately, for FCNC processes between a top quark and a charm quark (blue lines in Figure 3). Two interesting features can be observed in the distributions in Figure 3. First, the signal of the FCNC process in top-quark-pair decays is very well separated from backgrounds in the region targeting its signal (SR1), but not in the region targeting the FCNC production of a single top quark (SR2), and vice versa. Second, the sensitivity to the FCNC production of single top quarks is very dependent on whether an up quark or a charm quark initiates the process. As the colliding protons are themselves composed of up quarks and down quarks, the ingredients for an up-quark-initiated process are readily available. This results in good experimental sensitivity. By contrast, the charm-quark-initiated process arises from the constantly fluctuating mixture of “sea” quarks and gluons surrounding each proton, which carry a smaller proportion of the proton’s mass and energy. This reduces the probability for the charm-initiated process occurring, and subsequently reduces the experimental sensitivity. After applying the event selection, physicists compared the data to the SM background prediction, searching for an excess of events that could be an FCNC signal. A statistical analysis was performed to determine whether the number of data events in each bin was larger and statistically incompatible with the predicted number of SM events. No excess was found and limits on the probability of an FCNC top-quark decay into a Z boson and a light quark were obtained. The most stringent limits were set for the top-quark decay into a Z boson and an up quark, which is excluded at probabilities greater than approximately 6 in 100,000 top-quark decays. Figure 4: Summary of the current 95% confidence level observed limits on the branching ratios of the top quark decays via flavour-changing neutral currents (FCNC) to a quark and a neutral boson t → Xq (X = g, Z, ɣ or H; q = u or c) by the ATLAS and CMS Collaborations compared to several new physics models. Each limit assumes that all other FCNC processes vanish. The limits are expressed as FCNC top decay branching ratios, but several are obtained considering both FCNC top quark decay and FCNC top quark production vertices. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) The ATLAS Collaboration has performed many further FCNC searches for top quarks in association with gluons, photons and Higgs bosons, and for FCNC interactions of other particles such as the bottom quark. Figure 4 summarises the limits on the top-quark FCNC decay probabilities (branching ratios) obtained by the ATLAS (in blue) and the CMS (in red) Collaborations for various forbidden processes. The search for lepton flavour violation in Z-boson decays Searches for new physics phenomena have already led to the discovery of LFV in neutrinos, through the observation of neutrino oscillations. Neutrino oscillations could also induce LFV in electromagnetically-charged leptons. However, as the probability of this occurring is less than 1 in 1054, any observation would indicate an exciting additional discovery. A variety of experiments are currently searching for LFV processes with different lepton flavours and neutral bosons. This diversity of approaches is important, as new physics phenomena may interact with different leptons and bosons at different rates, and no single experiment can efficiently detect all LFV processes. At high-energy colliders, the most promising opportunities to study LFV processes involve the production of tau leptons alongside massive neutral bosons, such as the Z boson. The LHC, in its role as a Z-boson “factory,” provides fantastic opportunities to search for flavour-violating decays involving the Z boson, such as Z→e or Z→μ where a tau lepton is produced alongside a charged lepton of a different flavour. While searches for LFV involving lighter leptons and massless photons are also viable at the LHC, they can be searched for with greater accuracy in low-energy experiments, i.e. in searches for muon decays into an electron and a photon (μ → eɣ). The ATLAS Collaboration carried out a detailed search for flavour-violating Z→e and Z→μ processes. It was extremely challenging for several reasons, starting with the complicated task of spotting tau leptons. While electrons and muons can be directly detected by ATLAS, tau leptons have a lifetime of just 10–13 seconds and decay before they reach the experiment. The most common tau decay modes include leptonic decays to electrons or muons and their associated neutrinos, or to jets of quarks as described above. Thus, the signature of a flavour-violating Z→e or Z→μ process may well mimic other perfectly viable SM signatures, such as Z→ee. Figure 5: Diagrams of a LFV Z-boson decay (left) and of the two main SM processes which can produce final states experimentally similar to the LFV decays: a Z-boson decay into a pair of tau leptons (middle) and a W-boson decay into a light lepton and neutrino in association with an additional jet (right). The green arrows represent electrons or muons (l), the blue triangles are the jets produced by either the hadronic tau decay ( jet) or by a quark or a gluon (q/g jet), and the dashed blue lines indicate undetected neutrinos. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) Figure 5 (left) illustrates a flavour-violating Z-boson decay on a plane perpendicular to the proton beam direction. The unique feature of the LFV process is the alignment of the undetected neutrino (dashed line) and the tau lepton. This configuration, without any additional detected particles, cannot be produced by SM processes. Nevertheless, due to the random nature of quantum processes in the Universe and imperfections in experimental measurements, many SM processes can still look similar enough to cause a problem! The main SM lookalike is a Z-boson decay into a pair of tau leptons, where one tau lepton subsequently decays into a light lepton and two neutrinos and the other into a tau-jet and a neutrino. While the number of detected particles in this SM process matches that of the LFV decay, there’s a greater number of undetected neutrinos (see Figure 5, middle). The second most important SM lookalike involves a W boson produced in association with a jet, where the W-boson decays into a light lepton and a neutrino, and the jet originates from a quark or gluon misidentified as a hadronically decaying tau. In this case, the detected final state is also the same as in the LFV decay, but the neutrino is typically emitted in a direction close to the light lepton instead of the jet (see Figure 5, right). These kinematic differences are the key tool for isolating the LFV signature. Physicists designed a deep neural network (NN) to “learn” the kinematic properties of the signal events and how they differ on average from background events. NNs are extremely effective in this task as they can learn complex correlations among multiple features of an event. Figure 6 shows a histogram of events binned in a NN output (after applying the initial event selections). As with the BDTs in the FCNC searches, the events with high NN scores are more signal-like and the events with low values are more background-like. The red dashed line shows the expected distribution of signal events under an assumption that LFV decays occur as frequently as five in every 10,000 Z-boson decays. As with all previous measurements, no excess above the SM prediction was observed in the data. The ATLAS Collaboration set limits on LFV Z-boson decays into a tau and a light lepton that are stronger than those set by experiments on the Large Electron Positron (LEP) collider. At the 95% confidence level, the ATLAS result established that if these LFV decays do occur in nature, their probability must be less than about five in every one million Z-boson decays. Using similar analysis methods, physicists also set even more stringent limits on LFV Z-boson decays into an electron and a muon. The ATLAS Collaboration’s state-of-the-art searches for FCNC and LFV interactions have produced powerful probes of new physics phenomena. Figure 6: Distribution of recorded events (black points) and of simulated events (filled histograms) as a function of the NN output value. The yellow and blue histograms are the events from the W and Z boson decays shown in Figure 5, respectively. The distribution of the expected signal events is shown with the red dashed line. The lower panel shows the ratio in each bin of event yields in data to the event yields from simulated background processes. A value of unity indicates that the events in data are in agreement with the predicted backgrounds. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN) Outlook The ATLAS Collaboration’s state-of-the-art searches for FCNC and LFV interactions have produced powerful probes of new physics phenomena. Dedicated FCNC studies set limits on the FCNC top-quark decay branching ratio as tight as 10–5 (Figure 4), while further LFV searches focusing on Higgs-boson decays were also performed. The upper limits on the LFV decay probabilities of the Higgs boson are two orders of magnitude weaker than those for Z bosons, due to the much smaller number of Higgs bosons produced in LHC collisions and the more challenging task of distinguishing events with a Higgs boson from background processes. This sensitivity is expected to improve significantly with the collection of more data. ATLAS physicists also performed a search for a simultaneous FCNC and LFV process using Effective Field Theory in top-quark interactions with light quarks, muons and taus. Although this analysis is also statistically limited, it represents an exciting new direction for future studies. Since 2022, the LHC experiments have been collecting data from proton-proton collisions at a centre-of-mass energy of 13.6 TeV. This data-taking period is expected to provide approximately 1.5 times more Z bosons, Higgs bosons and top-quark pairs than in all previous runs, thanks to both the increased collision energy and the larger dataset ATLAS is recording. But larger datasets aren’t the only factor boosting searches for LFV and FCNC processes! Ongoing advancements in experimental methodologies and the ATLAS Collaboration’s deepening understanding of its ever-evolving detector will further improve sensitivity, driving searches for even rarer interactions. One continuous area of development is ATLAS’ in-house algorithms for identifying charm-quark-initiated jets, analogous to the existing and well-honed b-tagging capabilities. As mentioned above, limits on couplings involving the top and charm quarks are less stringent than those involving the up quark, and these algorithms will boost ATLAS’ charm-quark sensitivity. Looking ahead, further searches will be conducted following the completion of the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), for which the ATLAS experiment will undergo major upgrades to cope with the much higher luminosity. At the current LHC energy of 13.6 TeV, every time two bunches of protons cross each other an average of 50 overlapping collisions occur. This already makes event reconstruction very challenging. At the HL-LHC, this number will increase to approximately 200 simultaneous collisions. To address this complexity, a new silicon tracking detector, the Inner Tracker (ITk), will be installed in the ATLAS experiment. The ITk features new technologies that provide higher detection granularity, improved radiation hardness, faster readout speeds and a reduced material budget compared to the current inner detector – all of which will enable similar event reconstruction efficiencies to current data-taking, despite the much harsher future conditions. Moreover, the ITk’s extended coverage will enable ATLAS to reconstruct events in regions of the detector that are not currently equipped with a tracker, further extending and improving the data collection. The integrated luminosity that will be collected by the ATLAS experiment during the HL-LHC is expected to be 10 times greater than the total recorded at the LHC. This means that searches for very rare or forbidden processes, such as LFV and FCNC, will remain powerful, exciting and ever improving probes for physics beyond the Standard Model. About the Authors Lidia Dell’Asta joined the ATLAS Collaboration in 2007 while at the University of Milano. She then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at Boston University and as a research fellow at the University of Roma2. She is currently an associate professor at the University of Milano. In addition to her work on the detector trigger system, where she coordinated the muon trigger group, she has been active in data analysis. She has worked on Standard Model measurements as well as the measurement of the coupling of the Higgs boson to tau leptons. Over the past ten years, her research has focused on rare production processes of single top quarks, and she has served as a convener of the Single Top group. She has contributed to the measurement of single top quark production in association with a Z boson and to the search for top–Z FCNC couplings. Jacob Julian Kempster joined the ATLAS Collaboration in 2011 while at Royal Holloway, University of London. He subsequently worked as a Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham and is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sussex. His research focuses on using the top quark as a tool to search for new physics beyond the Standard Model. He performed the first ATLAS search for lepton flavor violating (LFV) couplings of the top quark to muons and tau leptons, and previously served as a subgroup convener for the Top+X working group. His other primary research area is Effective Field Theory (EFT), where he leads efforts on global EFT fits and recently completed his term as Chair of the LHC EFT Working Group. Daniele Zanzi was an active member of the ATLAS Collaboration until 2024. As researcher at the University of Melbourne, at CERN, and at the University of Freiburg, he has focussed on searching for LFV interactions. He has also contributed to the development and operation of the ATLAS trigger system, to measurements of the Higgs boson properties and to searches for dark matter and supersymmetric particles. About the banner image: Visualisation of a H →μτ candidate event, with the μτe (top) and μτhad (bottom) channel. An electron track is shown in green, a red line indicates a muon. A τhad-vis candidate is displayed in purple, the ETmiss is shown by a white dashed line. (Image: ATLAS Collaboration) Further reading ATLAS looks for top quarks going against the current, ATLAS Physics Briefing, May 2022 New ATLAS result marks milestone in the test of Standard Model properties, ATLAS Physics Briefing, August 2020 Scientific articles Search for flavor-changing neutral-current couplings between the top quark and the boson with proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 32,019, arXiv:2301.11605, see figures) Search for flavour-changing neutral-current interactions of a top quark and a gluon in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (Eur. Phys. J. C 82 (2022) 334, arXiv:2112.01302, see figures) Search for flavour-changing neutral-current couplings between the top quark and the photon with the ATLAS detector at 13 TeV (Phys. Lett. B 842 (2023) 137,379, arXiv:2205.02537, see figures) Search for flavour-changing neutral-current couplings between the top quark and the Higgs boson in multi-lepton final states in 13 TeV proton-proton collisions with the ATLAS detector (Eur. Phys. J. C 84 (2024) 757, arXiv:2404.02123, see figures) Top Quarks + X Summary Plots April 2024 (ATL-PHYS-PUB-2024–005) Search for charged-lepton-flavour violation in Z-boson decays with the ATLAS detector (Nature Phys. 17 (2021) 819, arXiv:2010.02566, see figures) Search for the charged-lepton-flavor-violating decay → in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (Phys. Rev. D 108 (2023) 32,015, arXiv:2204.10783, see figures) Searches for lepton-flavour-violating decays of the Higgs boson into eτ and μτ in 13 TeV proton-proton collisions with the ATLAS detector (JHEP 7 (2023) 166, arXiv:2302.05225, see figures) Search for charged-lepton-flavor violating interactions in top-quark production and decay in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector at the LHC (Phys. Rev. D 110 (2024) 12,014, arXiv:2403.06742, see figures) The ATLAS ITk detector system for the Phase-II LHC upgrade (Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 1,045 (2023) 167597) Search for flavour-changing neutral tqH interactions with H→γγ in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV using the ATLAS detector (JHEP 12 (2023) 195, arXiv:2309.12817, see figures) Search for flavour-changing neutral current interactions of the top quark and the Higgs boson in events with a pair of τ-leptons in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (JHEP 6 (2023) 155, arXiv:2208.11415, see figures)