𝐀𝐥𝐳𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞

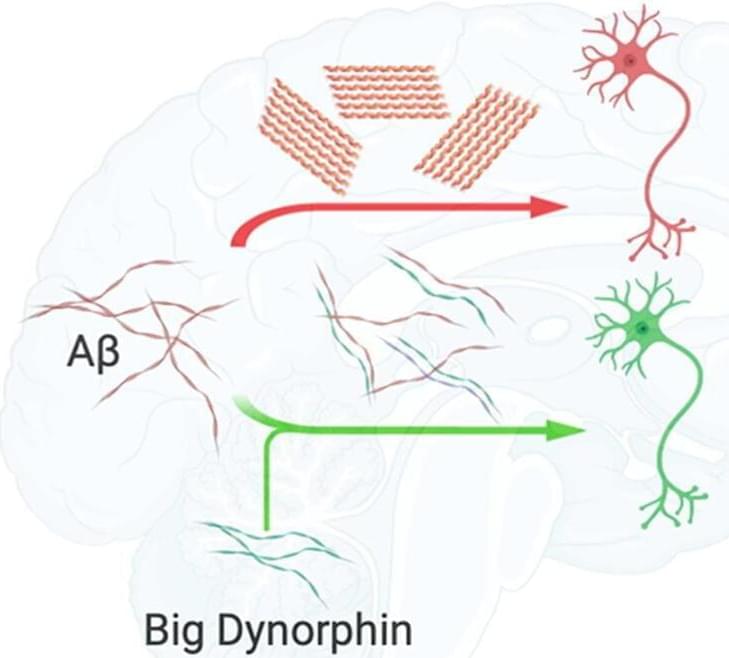

One of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease is that the β-amyloid peptide, a molecule found inside neurons that has many diverse functions, begins to fold incorrectly and accumulates. This process, which ends up causing neuronal death, is linked to a series of other cellular alterations, making it difficult to determine whether they are the cause or the consequence. An example is the case of the deregulation of a type of dynorphin.

Dynorphins are the body’s own opioid peptides, which play a key role in many brain pathways. They are located in different areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus, amygdala or hypothalamus, and are involved in memory processes, emotion control, stress and pain, and among other processes. In addition, several studies have shown their involvement in epilepsy, stroke, addictions, depression and schizophrenia.

Now, in a study published in the Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, a research group led by Àlex Perálvarez-Marín, researcher in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the UAB Institut de Neurociències, has studied from computer models and cell cultures which interactions may exist between β-amyloid peptide and big dynorphin, to determine its role in β-amyloid accumulation.