Real-world science may show that the brain-controlling zombie Fungi from The Last Of Us franchise may actually be a threat to humanity.

A new study led by scientists at Rutgers University has uncovered new insights into the underlying brain mechanisms of autism spectrum disorder.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex developmental disorder that affects how a person communicates and interacts with others. It is characterized by difficulty with social communication and interaction, as well as repetitive behaviors and interests. ASD can range from mild to severe, and individuals with ASD may have a wide range of abilities and challenges. It is a spectrum disorder because the symptoms and characteristics of ASD can vary widely from person to person. Some people with ASD are highly skilled in certain areas, such as music or math, while others may have significant learning disabilities.

If a brain is uploaded into a computer, will consciousness continue in digital form or will it end forever when the brain is destroyed? Philosophers have long debated such dilemmas and classify them as questions about personal identity. There are currently three main theories of personal identity: biological, psychological, and closest continuer theories. None of these theories can successfully address the questions posed by the possibility of uploading. I will argue that uploading requires us to adopt a new theory of identity, psychological branching identity. Psychological branching identity states that consciousness will continue as long as there is continuity in psychological structure. What differentiates this from psychological identity is that it allows identity to continue in multiple selves.

All four participants were able to send out neural signals.

Medical technology company Synchron published in a press release on Monday the results of a clinical study that saw paralyzed patients effectively send out neural signals via an implantable brain-computer interface.

The study highlighted the long-term safety results from a clinical study in which four patients with severe paralysis implanted with Synchron’s first-generation Stentrode, a neuroprosthesis device, were able to control a computer.

They say that actors ought to fully immerse themselves into their roles. Uta Hagen, acclaimed Tony Award-winning actress and a legendary acting teacher said this: “It’s not about losing yourself in the role, it’s about finding yourself in the role.”

In today’s column, I’m going to take you on a journey of looking at how the latest in Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used for role-playing. This is not merely play-acting. Instead, people are opting to use a type of AI known as Generative AI including the social media headline-sparking AI app ChatGPT as a means of seeking self-growth via role-playing.

You might be wondering why I didn’t showcase a more alarming example of generative AI role-playing. I could do so, and you can readily find such examples online. For example, there are fantasy-style role-playing games that have the AI portray a magical character with amazing capabilities, all of which occur in written fluency on par with a human player. The AI in its role might for example try to (in the role-playing scenario) expunge the human player or might berate the human during the role-playing game.

My aim here was to illuminate the notion that role-playing doesn’t have to necessarily be the kind that clobbers someone over the head and announces itself to the world at large. There are subtle versions of role-playing that generative AI can undertake. Overall, whether the generative AI is full-on role-playing or performing in a restricted mode, the question still stands as to what kind of mental health impacts might this functionality portend. There are the good, the bad, and the ugly associated with generative AI and role-playing games.

On a societal basis, we ought to be deciding what makes the most sense. Otherwise, the choices are left in the hands of those that perchance are programming and devising generative AI. It takes a village to make sure that AI is going to be derived and fielded in an AI Ethically sound manner, and likewise going to abide by pertinent AI laws if so established.

Why do cells, and by extension humans, age? The answer may have a lot to do with mitochondria, the organelles that supply cells with energy. Though that idea is not new, direct evidence in human cells had been lacking. Until now.

In a study published Jan. 12 in Communications Biology, a team led by Columbia University researchers has discovered that human cells with impaired mitochondria respond by kicking into higher gear and expending more energy. While this adaptation—called hypermetabolism—enhances the cells’ short-term survival, it comes at a high cost: a dramatic increase in the rate at which the cells age.

“The findings were made in cells from patients with rare mitochondrial diseases, yet they may also have relevance for other conditions that affect mitochondria, including neurodegenerative diseases, inflammatory conditions, and infections,” says principal investigator Martin Picard, PhD, associate professor of behavioral medicine (in psychiatry and neurology) at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

When people are in a negative mood, they may be quicker to spot inconsistencies in things they read, a new University of Arizona-led study suggests.

The study, published in Frontiers in Communication, builds on existing research on how the brain processes language.

Vicky Lai, a UArizona assistant professor of psychology and cognitive science, worked with collaborators in the Netherlands to explore how people’s brains react to language when they are in a happy mood versus a negative mood.

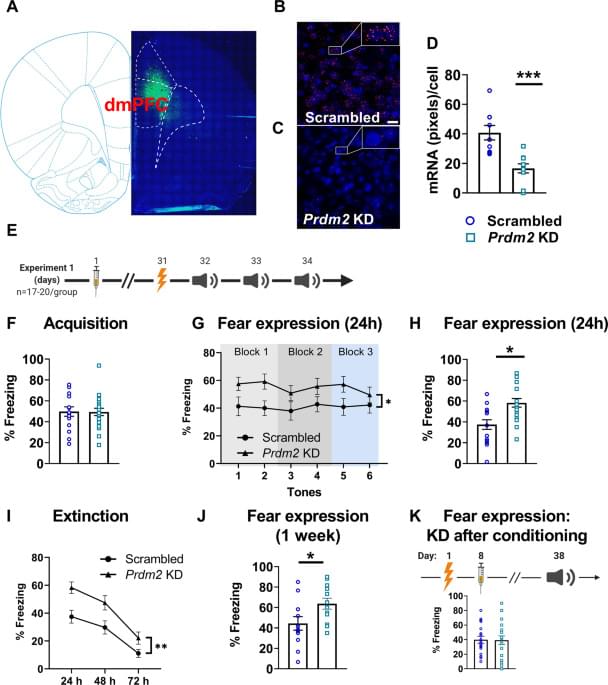

Excessive fear is a hallmark of anxiety disorders, a major cause of disease burden worldwide. Substantial evidence supports a role of prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuits in the regulation of fear and anxiety, but the molecular mechanisms that regulate their activity remain poorly understood. Here, we show that downregulation of the histone methyltransferase PRDM2 in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex enhances fear expression by modulating fear memory consolidation. We further show that Prdm2 knock-down (KD) in neurons that project from the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex to the basolateral amygdala (dmPFC-BLA) promotes increased fear expression. Prdm2 KD in the dmPFC-BLA circuit also resulted in increased expression of genes involved in synaptogenesis, suggesting that Prdm2 KD modulates consolidation of conditioned fear by modifying synaptic strength at dmPFC-BLA projection targets.

The rebooting came in the form of a gene therapy involving three genes that instruct cells to reprogram themselves—in the case of the mice, the instructions guided the cells to restart the epigenetic changes that defined their identity as, for example, kidney and skin cells, two cell types that are prone to the effects of aging. These genes came from the suite of so-called Yamanaka stem cells factors—a set of four genes that Nobel scientist Shinya Yamanaka in 2006 discovered can turn back the clock on adult cells to their embryonic, stem cell state so they can start their development, or differentiation process, all over again. Sinclair didn’t want to completely erase the cells’ epigenetic history, just reboot it enough to reset the epigenetic instructions. Using three of the four factors turned back the clock about 57%, enough to make the mice youthful again.

“We’re not making stem cells, but turning back the clock so they can regain their identity,” says Sinclair. “I’ve been really surprised by how universally it works. We haven’t found a cell type yet that we can’t age forward and backward.”

Rejuvenating cells in mice is one thing, but will the process work in humans? That’s Sinclair’s next step, and his team is already testing the system in non-human primates. The researchers are attaching a biological switch that would allow them to turn the clock on and off by tying the activation of the reprogramming genes to an antibiotic, doxycycline. Giving the animals doxycycline would start reversing the clock, and stopping the drug would halt the process. Sinclair is currently lab-testing the system with human neurons, skin, and fibroblast cells, which contribute to connective tissue.

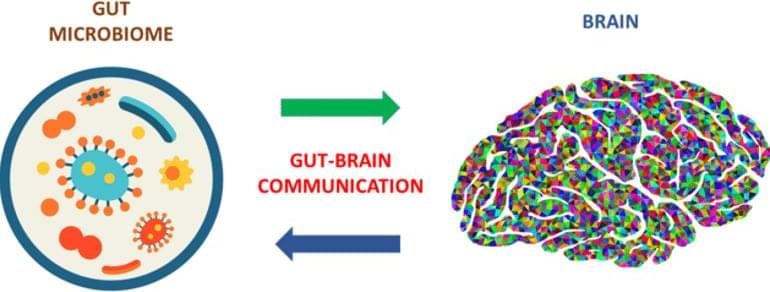

Summary: Researchers develop a novel tool that allows for the study of the communication of microbes in the gastrointestinal tract and the brain.

Source: Baylor College of Medicine.

In the past decade, researchers have begun to appreciate the importance of a two-way communication that occurs between microbes in the gastrointestinal tract and the brain, known as the gut–brain axis.