Aging clocks estimate how fast specific organs are deteriorating—but it’s hard to know what to do with the results.

Get early access to our latest psychology lectures: http://bit.ly/new-talks5

If I have a visual experience that I describe as a red tomato a meter away, then I am inclined to believe that there is, in fact, a red tomato a meter away, even if I close my eyes. I believe that my perceptions are, in the normal case, veridical—that they accurately depict aspects of the real world. But is my belief supported by our best science? In particular: Does evolution by natural selection favor veridical perceptions? Many scientists and philosophers claim that it does. But this claim, though plausible, has not been properly tested. In this talk, I present a new theorem: Veridical perceptions are never more fit than non-veridical perceptions which are simply tuned to the relevant fitness functions. This entails that perception is not a window on reality; it is more like a desktop interface on your laptop. I discuss this interface theory of perception and its implications for one of the most puzzling unsolved problems in science: the relationship between brain activity and conscious experiences.

Prof. Donald Hoffman, PhD received his PhD from MIT, and joined the faculty of the University of California, Irvine in 1983, where he is a Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Sciences. He is an author of over 100 scientific papers and three books, including Visual Intelligence, and The Case Against Reality. He received a Distinguished Scientific Award from the American Psychological Association for early career research, the Rustum Roy Award of the Chopra Foundation, and the Troland Research Award of the US National Academy of Sciences. His writing has appeared in Edge, New Scientist, LA Review of Books, and Scientific American and his work has been featured in Wired, Quanta, The Atlantic, and Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman. You can watch his TED Talk titled “Do we see reality as it is?” and you can follow him on Twitter @donalddhoffman.

Links:

- Get our latest psychology lectures emailed to your inbox: http://bit.ly/new-talks5

- Check out our next event: http://theweekenduniversity.com/events/

EXPERTS:

It’s a step that could one day lead to advances for humans that boost quality of life for many by: giving amputees and those with spinal injuries control of advanced prosthetics, stimulating the sacral nerve to restore bladder control, stimulating the cervical vagus nerve to treat epilepsy and providing deep brain stimulation as a possible treatment for Parkinson’s.

How far would you go to keep your mind from failing? Would you go so far as to let a doctor drill a hole in your skull and stick a microchip in your brain?

It’s not an idle question. In recent years neuroscientists have made major advances in cracking the code of memory, figuring out exactly how the human brain stores information and learning to reverse-engineer the process. Now they’ve reached the stage where they’re starting to put all of that theory into practice.

Last month two research teams reported success at using electrical signals, carried into the brain via implanted wires, to boost memory in small groups of test patients. “It’s a major milestone in demonstrating the ability to restore memory function in humans,” says Dr. Robert Hampson, a neuroscientist at Wake Forest School of Medicine and the leader of one of the teams.

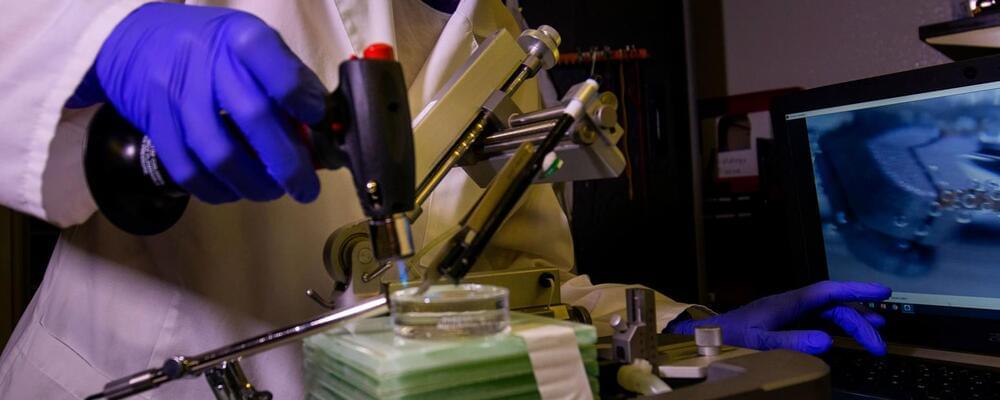

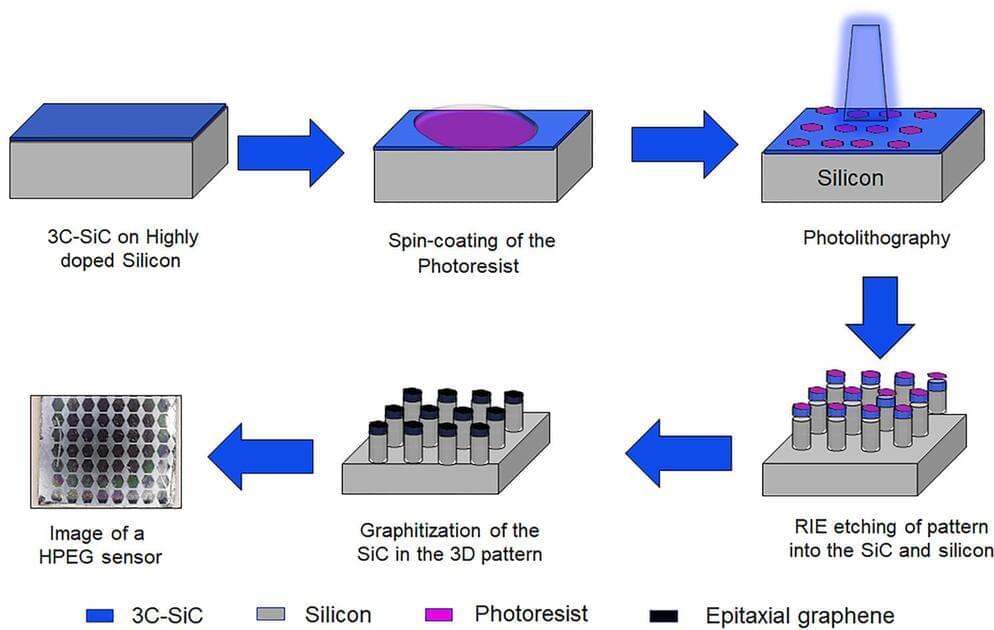

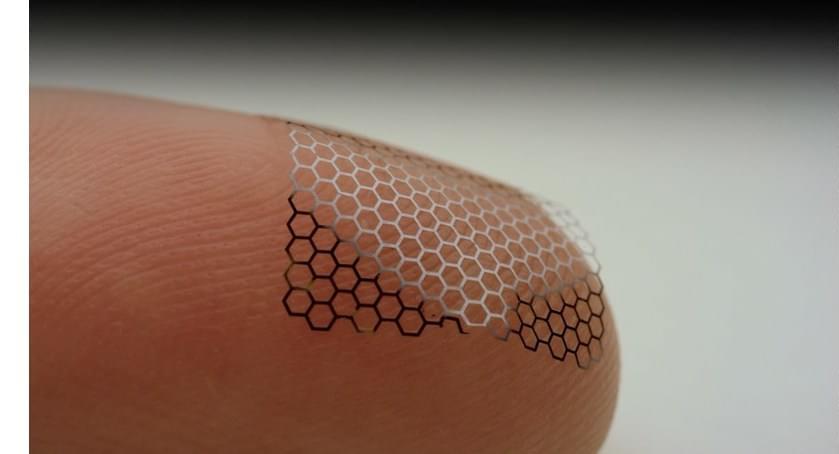

As fun as brain-computer interfaces (BCI) are, for the best results they tend to come with the major asterisk of requiring the cutting and lifting of a section of the skull in order to implant a Utah array or similar electrode system. A non-invasive alternative consists out of electrodes which are placed on the skin, yet at a reduced resolution. These electrodes are the subject of a recent experiment by [Shaikh Nayeem Faisal] and colleagues in ACS Applied NanoMaterials employing graphene-coated electrodes in an attempt to optimize their performance.

Although external electrodes can be acceptable for basic tasks, such as registering a response to a specific (visual) impulse or for EEG recordings, they can be impractical in general use. Much of this is due to the disadvantages of the ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ varieties, which as the name suggests involve an electrically conductive gel with the former.

This gel ensures solid contact and a resistance of no more than 5 – 30 kΩ at 50 Hz, whereas dry sensors perform rather poorly at 200 kΩ at 50 Hz with worse signal-to-noise characteristics, even before adding in issues such as using the sensor on a hairy scalp, as tends to be the case for most human subjects.

Neuralace™ is a glimpse of what’s possible in the future of BCI.

This patent pending concept technology is the start of Blackrock’s journey toward whole-brain data capture–with transformative potential for the way neurological disorders are treated. With over 10,000 channels and a flexible lace structure that seamlessly conforms to the brain, Neuralace has potential applications in vision and memory restoration, performance prediction, and the treatment of mental health disorders like depression.

Neuralace is:

Ultra-High Channel Count | Wireless | Customizable | Flexible | Thinner than an eyelash.

The possibilities are endless… Whole-brain data capture | Seamless connectivity | Improved biocompatibility About Blackrock Neurotech Blackrock Neurotech is a team of the world’s leading engineers, neuroscientists, and visionaries. Our mission is simple: We want people with neurological disorders to walk, talk, see, hear, and feel again. We’re engineering the next generation of neural implants, including implantable brain-computer interface technology that restores function and independence to individuals with neurological disorders. Join us in changing lives today. Connect with us: Join Our Team | https://bit.ly/3bCsXRv LinkedIn | https://bit.ly/3PfifOL Twitter | https://bit.ly/3PfifOL Instagram | https://bit.ly/3bMaYrW Facebook | https://bit.ly/3JRc2av Clinical Trials | https://bit.ly/3A8QPWm Our site | https://blackrockneurotech.com.

Whole-brain data capture | Seamless connectivity | Improved biocompatibility.

About Blackrock Neurotech.

Blackrock Neurotech is a team of the world’s leading engineers, neuroscientists, and visionaries. Our mission is simple: We want people with neurological disorders to walk, talk, see, hear, and feel again. We’re engineering the next generation of neural implants, including implantable brain-computer interface technology that restores function and independence to individuals with neurological disorders. Join us in changing lives today.

Connect with us:

Blackrock’s long-tested NeuroPort® Array, widely considered the gold standard of high-channel neural interfacing, has been used in human BCIs since 2004 and powered many of the field’s most significant milestones. In clinical trials, patients using Blackrock’s BCI have regained tactile function, movement of their own limbs and prosthetics, and the ability to control digital devices, despite diagnoses of paralysis and other neurological disorders.

While Blackrock’s BCI enables patients to execute sophisticated functions without reliance on assistive technologies, next-generation BCIs for areas such as vision and memory restoration, performance prediction, and treatment of mental health disorders like depression will need to interface with more neurons.

Neuralace is designed to capitalize on this need; with 10,000+ channels and the entire scalable system integrated on an extremely flexible lace-structured chip, it could capture data that is orders of magnitude greater than existing electrodes, allowing for an exponential increase in capability and intuitiveness.

A book talk by:

Robert Stickgold, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry.

Harvard Medical School.

Director, center for sleep and cognition.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Resolving activity in cortical columns and cortical layers in the human brain with ultra-high field fMRI — new insights for biological models of cognitive functions.

Speaker: Rainer Goebel, Maastricht University, Netherlands.

HBP School — The Human Brain Atlas: Neuroscientific basis, tools and applications.

3–7 September 2018

Düsseldorf/Jülich, Germany.

Maastricht, Netherlands.

Follow us:

Facebook: @hbpeducation.

Twitter: @hbp_education.

Instagram: @hbp_education or visit:

www.humanbrainproject.eu/education.

Video recorded by Bergrath & Siebert.