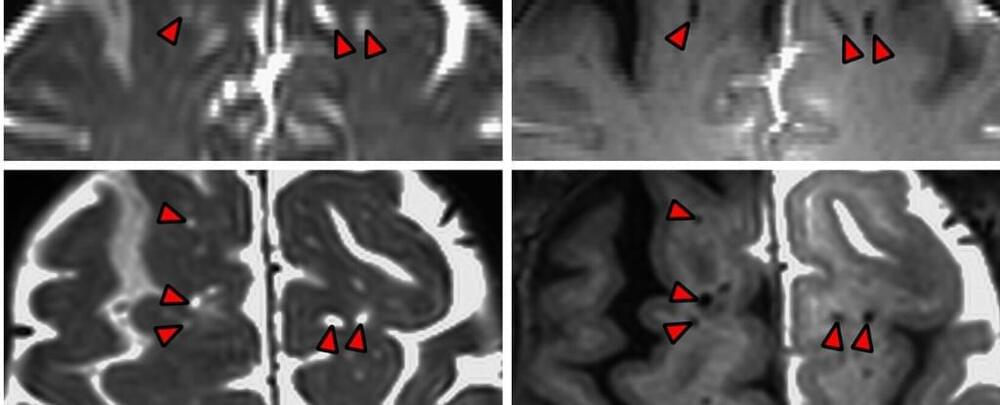

Although intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) is a known risk factor for cerebrovascular ischemic events, its potential role in dementia risk remains unclear. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study was a prospective cohort study that recruited participants from four U.S. communities. From 2011 to 2013, a subset comprising 1,590 participants (mean age, 77; 40% men; 28% Black) underwent ICAD evaluation and neurocognitive testing to ascertain the prospective association of ICAD with dementia risk, independent of other known cardiovascular risk factors. ICAD was diagnosed based on focal-wall thickness on brain MRI, with or without luminal stenosis on magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years, 286 cases of incident dementia were observed. After adjustment for established dementia risk factors, including cardiovascular risk factors, patients with ICAD (regardless of luminal stenosis) had an independently higher risk for incident dementia than those without ICAD (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.17–2.11). The presence of stenosis 50% on MRA was associated with even higher risk (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.29–2.78). An important limitation was the investigators’ inability to determine dementia subtypes.

This prospective trial adds further observational evidence that ICAD is independently associated with dementia. Furthermore, this study provides evidence that earlier stages of atherosclerosis (i.e., involvement of the arterial wall without luminal narrowing) are also associated with increased risk. While the pathophysiology of this association has yet to be elucidated, I will counsel my patients with ICAD about this association and will strongly recommend proven management strategies (e.g., smoking cessation, lipid lowering) to mitigate vascular disease progression, given the higher risk of dementia in those with luminal disease.