PHOENIX — Mayo Clinic announces the results of an innovative treatment approach that may offer improvement in overall survival in older patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma while maintaining quality of life. Glioblastoma is the most lethal type of primary brain cancer due to its aggressive nature and its treatment-resistant characteristics. It is the most common form of primary brain cancer. Each year an estimated 14,500 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with the disease. Results of Mayo Clinic’s phase 2, single-arm study are published in The Lancet Oncology.

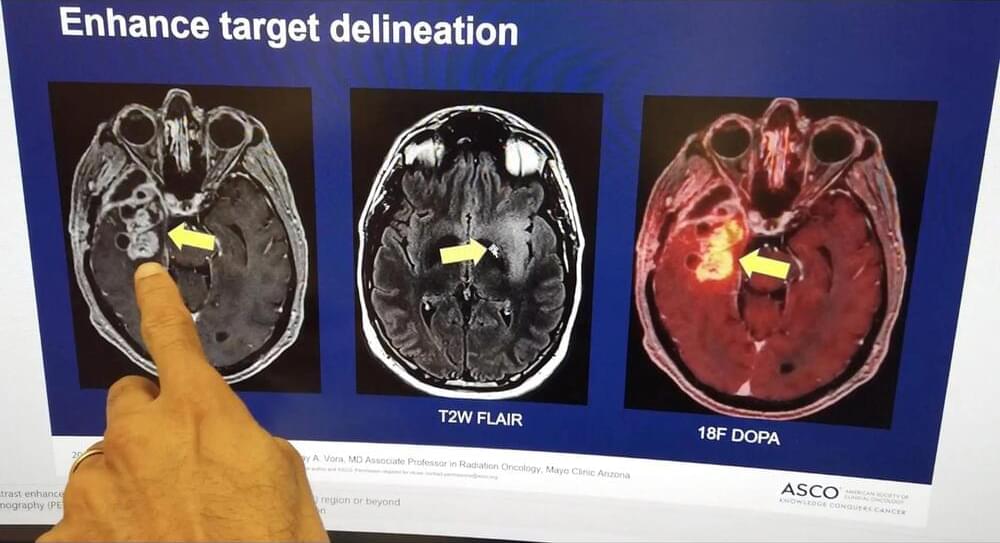

Sujay Vora, M.D., radiation oncologist at Mayo Clinic, led a team of researchers investigating the use of short-course hypofractionated proton beam therapy incorporating advanced imaging techniques in patients over the age of 65 with newly diagnosed World Health Organization (WHO) grade 4, malignant glioblastoma.

Results showed that 56% of participants were alive after 12 months and the median overall survival was 13.1 months.” As compared to prior phase 3 studies in an older population having a median survival of only six to nine months, these results are promising,” says Dr. Vora. “In some cases, patients with tumors that have favorable genetics lived even longer, with a median survival of 22 months. We are very excited about these results.”