Improvements to brain–computer interfaces are bringing the technology closer to natural conversation speed.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects approximately 1% of people over the age of 60 and 5% of those over the age of 85. Current drugs for Parkinson’s disease mainly affect the symptoms and cannot stop its progression. Nanotechnology provides a solution to address some challenges in therapy, such as overcoming the blood-brain barrier (BBB), adverse pharmacokinetics, and the limited bioavailability of therapeutics. The reformulation of drugs into nanoparticles (NPs) can improve their biodistribution, protect them from degradation, reduce the required dose, and ensure target accumulation. Furthermore, appropriately designed nanoparticles enable the combination of diagnosis and therapy with a single nanoagent.

In recent years, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have been studied with increasing interest due to their intrinsic nanozyme activity. They can mimic the action of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase. The use of 13-nm gold nanoparticles (CNM-Au8®) in bicarbonate solution is being studied as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease and other neurological illnesses. CNM-Au8® improves remyelination and motor functions in experimental animals.

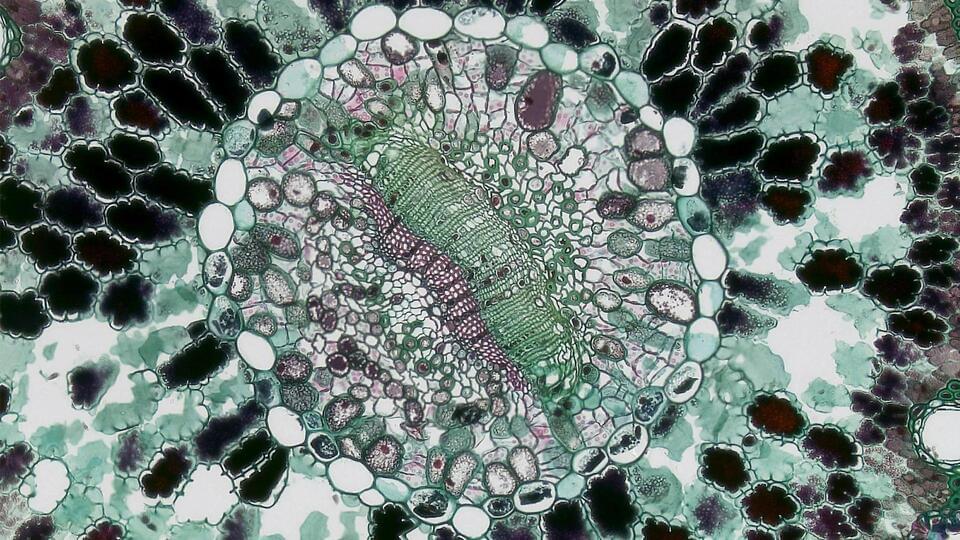

Among the many techniques for nanoparticle synthesis, green synthesis is increasingly used due to its simplicity and therapeutic potential. Green synthesis relies on natural and environmentally friendly materials, such as plant extracts, to reduce metal ions and form nanoparticles. Moreover, the presence of bioactive plant compounds on their surface increases the therapeutic potential of these nanoparticles. The present article reviews the possibilities of nanoparticles obtained by green synthesis to combine the therapeutic effects of plant components with gold.

Biological systems, once thought too chaotic for quantum effects, may be quietly leveraging quantum mechanics to process information faster than anything man-made.

New research suggests this isn’t just happening in brains, but across all life, including bacteria and plants.

Schrödinger’s legacy inspires a quantum leap.

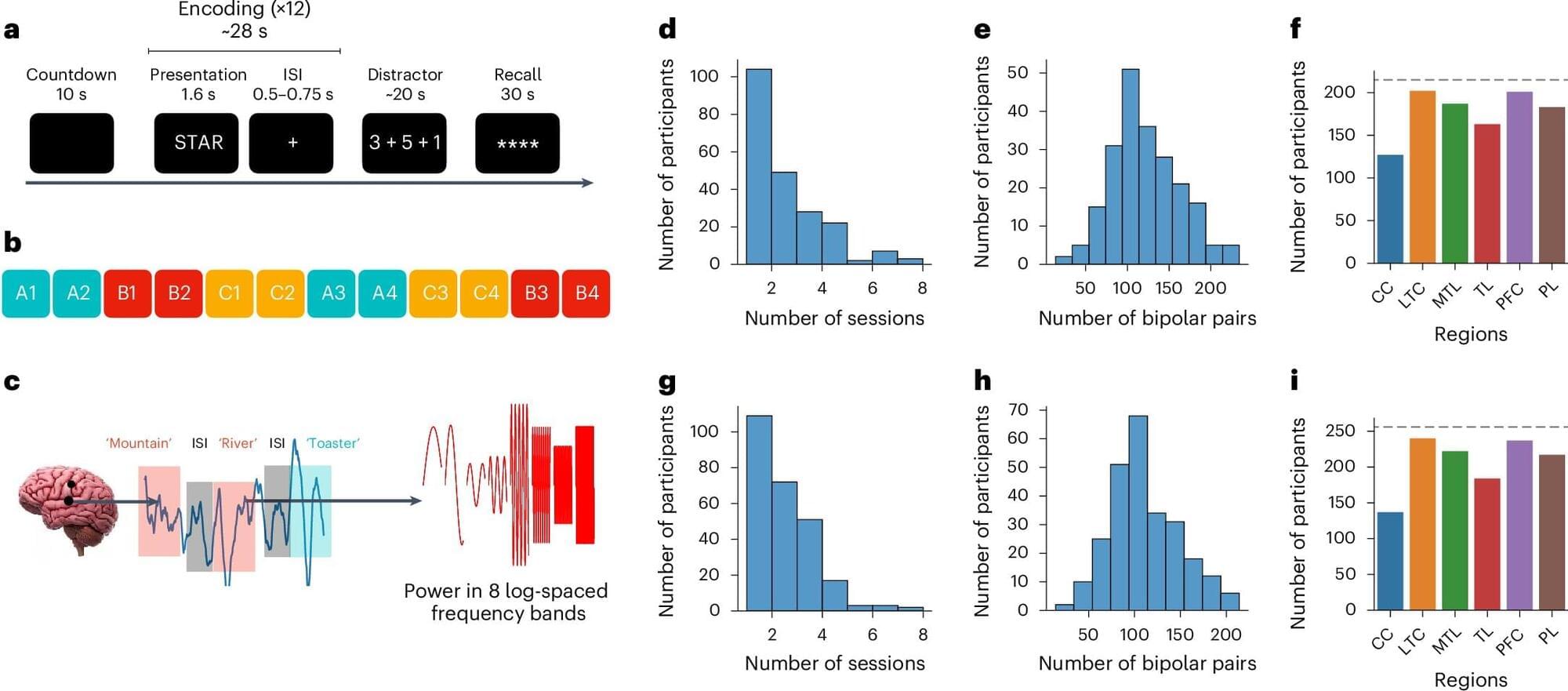

Past neuroscience and psychology studies have shown that after the human brain encodes specific events or information, it can periodically reactivate them to facilitate their retention, via a process known as memory consolidation. The reactivation of memories has been specifically studied in the context of sleep or rest, with findings suggesting that during periods of inactivity, the brain reactivates specific memories, allowing people to remember them in the long term.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and other institutions in the United States recently conducted a study exploring the possibility that the brain engages in a similar reactivation process during wakefulness to store important information for shorter periods of time. Their findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that the spontaneous reactivation of specific stimuli in the brain during the brief intervals between their encoding predicts the accuracy with which people remember them at the end of a memory task.

“Mike Kahana and I were both quite interested in the long history of thinking about rehearsal and its effects on the way in which people later recalled things,” Dr. David Halpern, the first author of the paper, told Medical Xpress. “Rehearsal is challenging to study since people often do it without any overt behavior (unless we ask them to rehearse out loud).”

While researchers continue to work on a full cure for Alzheimer’s disease, they’re finding treatments that can help manage symptoms and delay their onset, including the recently approved next-gen therapies lecanemab and donanemab.

Both treatments have been approved by US regulators in the last couple of years, and they work by clearing out some of the amyloid protein plaques in the brain that are linked to Alzheimer’s. However, there’s some debate over how effective they are.

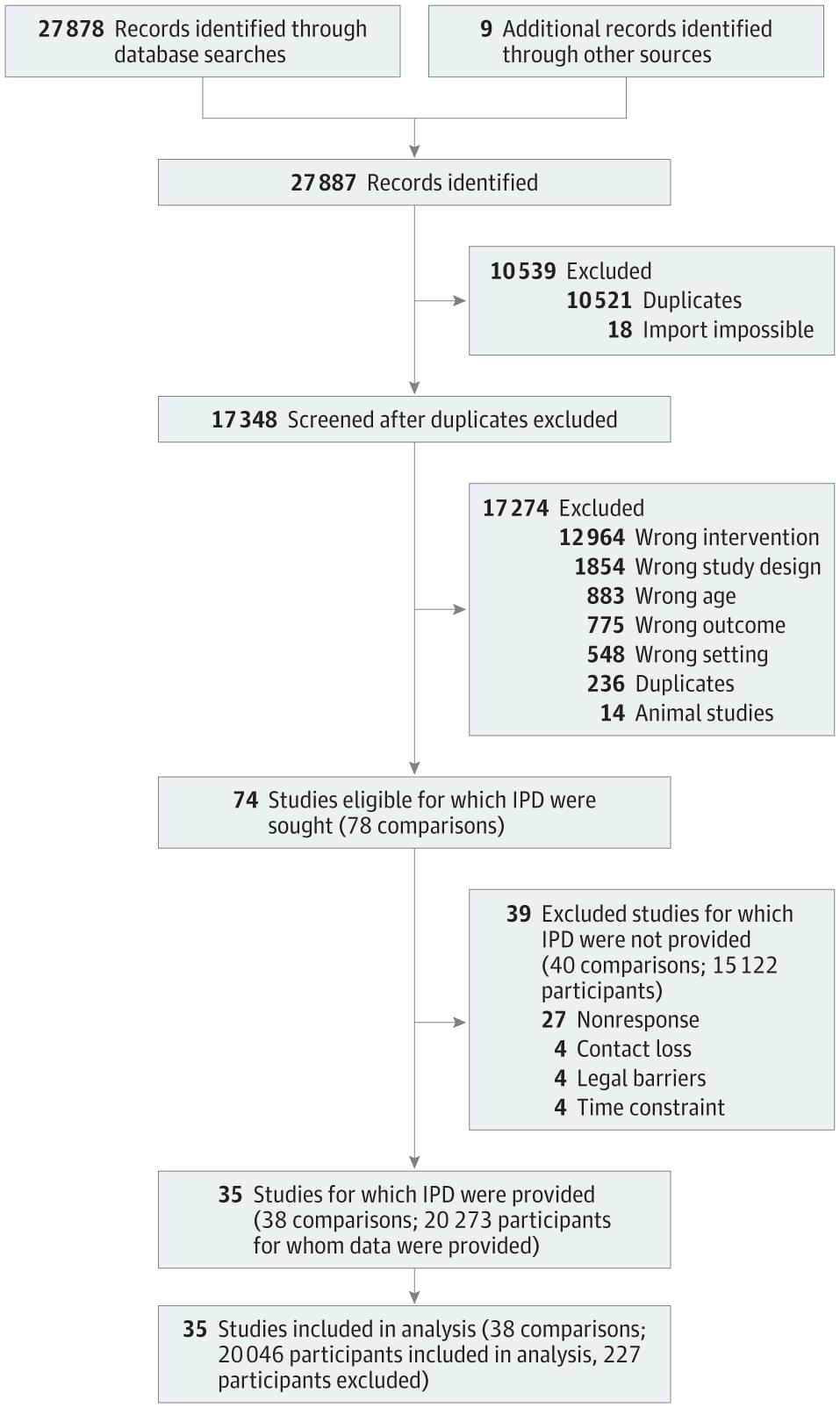

To quantify the effectiveness of lecanemab and donanemab in more meaningful terms, researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine (WashU Medicine) recruited 282 volunteers with Alzheimer’s, analyzing the impacts of taking these drugs over an average of nearly three years.