A mouse study at WashU Medicine shows how Alzheimer’s disease reprograms genes in specialized cells involved in amyloid plaque removal.

When you’re a teenager, it’s easy to feel like the world is watching your every mistake. For some kids, that sense of self‐consciousness fades as they grow up. For others, it deepens into full‐blown anxiety.

A new study led by researchers at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences may help explain why—and could eventually make it easier to spot teens most at risk before anxiety takes hold.

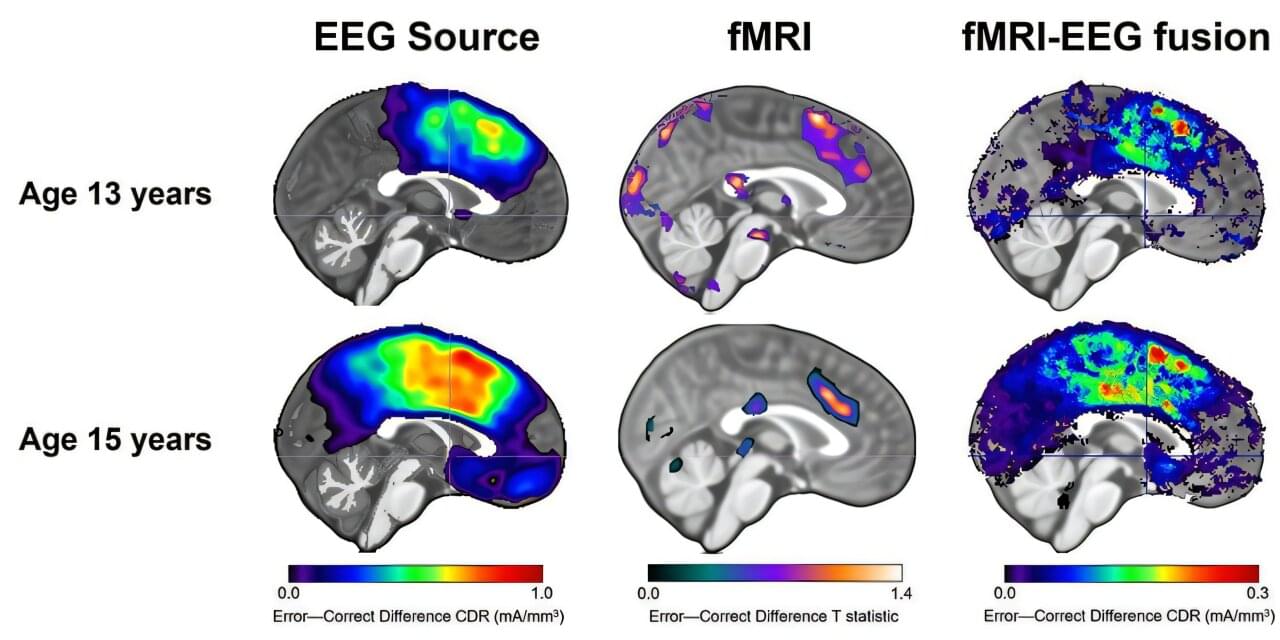

The research, published in JAMA Network Open, found that combining two kinds of brain scans can better predict which teens are likely to experience greater anxiety as they get older. The work sheds new light on how the adolescent brain responds to mistakes and why those responses vary from person to person.

Subscribe and follow along:https://www.youtube.com/@neuralbasisofconsciousnessPLAYLIST (will be updated as new videos are released)TALKS:https://www.youtube…

Jeremy Barton and Nanotechnology.

*This video was recorded at ‘Paths to Progress’ at LabWeek hosted by Protocol Labs & Foresight Institute.*

Protocol Labs and Foresight Institute are excited to invite you to apply to a 5-day mini workshop series to celebrate LabWeek, PL’s decentralized conference to further public goods. The theme of the series, Paths to Progress, is aimed at (re)-igniting long overdue progress in longevity bio, molecular nanotechnology, neurotechnology, crypto & AI, and space through emerging decentralized, open, and technology-enabled funding mechanisms.

*This mini-workshop is focused on Paths to Progress in Molecular Nanotechnology*

Molecular manufacturing, in its most ambitious incarnation, would use programmable tools to bring together molecules to make precisely bonded components in order to build larger structures from the ground up. This would enable general-purpose manufacturing of new materials and machines, at a fraction of current waste and price. We are currently nowhere near this ambitious goal. However, recent progress in sub-fields such as DNA nanotechnology, protein-engineering, STM, and AFM provide possible building blocks for the construction of a v1 of molecular manufacturing; the molecular 3D printer. Let’s explore the state of the art and what type of innovation mechanisms could bridge the valley of death: how might we update the original Nanotech roadmap; is a tech tree enough? how might we fund the highly interdisciplinary progress needed to succeed: FRO vs. DAO?

*About The Foresight Institute*

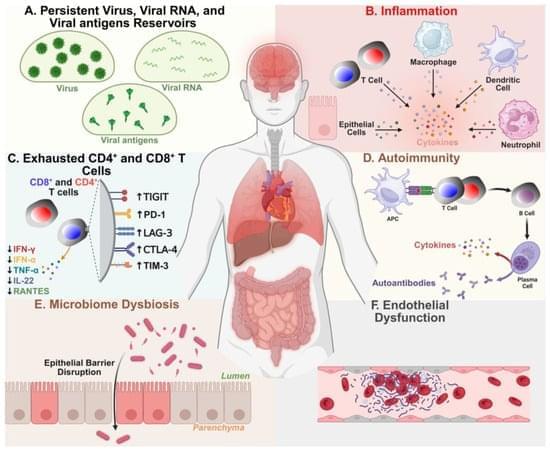

Long COVID (LC), also known as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 infection (PASC), is a heterogeneous and debilitating chronic disease that currently affects 10 to 20 million people in the U.S. and over 420 million people globally. With no approved treatments, the long-term global health and economic impact of chronic LC remains high and growing. LC affects children, adolescents, and healthy adults and is characterized by over 200 diverse symptoms that persist for months to years after the acute COVID-19 infection is resolved. These symptoms target twelve major organ systems, causing dyspnea, vascular damage, cognitive impairments (“brain fog”), physical and mental fatigue, anxiety, and depression. This heterogeneity of LC symptoms, along with the lack of specific biomarkers and diagnostic tests, presents a significant challenge to the development of LC treatments.

It sounds like science fiction, but the system could boost collaborative rehabilitation, where groups of people with brain or spinal cord injuries work together. By showing rather than telling Denapoli how to move her hand, she’s nearly doubled her hand strength since starting the trial.

“Crucially, this approach not only restores aspects of sensorimotor function,” wrote the team. It “also fosters interpersonal connection, allowing individuals with paralysis to re-experience agency, touch, and collaborative action through another person.”

We move without a second thought: pouring a hot cup of coffee while half awake, grabbing a basketball versus a tennis ball, or balancing a cup of ice cream instead of a delicate snow cone.