The development of humans and other animals unfolds gradually over time, with cells taking on specific roles and functions via a process called cell fate determination. The fate of individual cells, or in other words, what type of cells they will become, is influenced both by predictable biological signals and random physiological fluctuations.

Over the past decades, medical researchers and neuroscientists have been able to study these processes in greater depth, using a technique known as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). This is an experimental tool that can be used to measure the gene activity of individual cells.

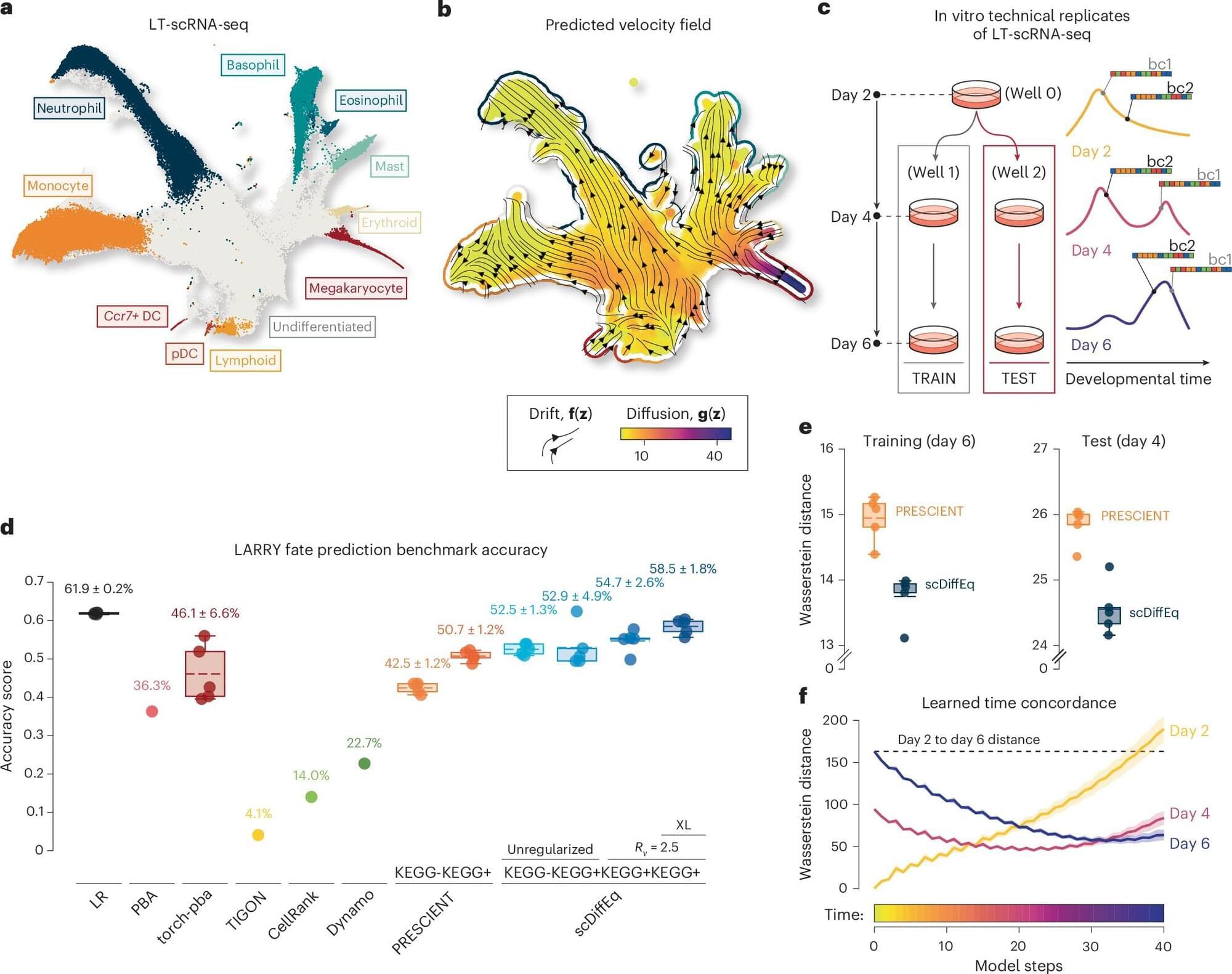

To better understand how cells develop over time, researchers also rely on mathematical models. One of these models, dubbed the drift-diffusion equation, describes the evolution of systems as the combination of predictable changes (i.e., drift) and randomness (i.e., diffusion).