A new framework that embeds electrons in a surrounding bath captures nonlocal correlation effects that are relevant to metals, semiconductors, and correlated insulators.

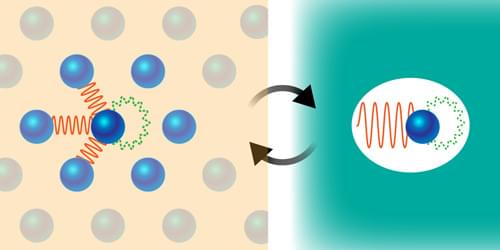

Searching for new types of superconductors, magnets, and other useful materials is a bit like weaving a tapestry with threads of many different colors. The weaver selects a short-range (local) pattern for how the individual threads intertwine and at the same time chooses colors that will give an overall (nonlocal) mood. A materials scientist works in a similar way, mixing atoms instead of threads, trying to match the motion of their electrons—their correlations—on both local and nonlocal scales. Doing so by trial-and-error synthesis is time intensive and costly, and therefore numerical simulations can be of huge help. To contribute to bridging computations to material discovery, Jiachen Li and Tianyu Zhu from Yale University have developed a new approach that treats local and nonlocal electronic correlations on an equal footing [1] (Fig. 1). They demonstrated their method by accurately predicting the photoemission spectra of several representative materials.