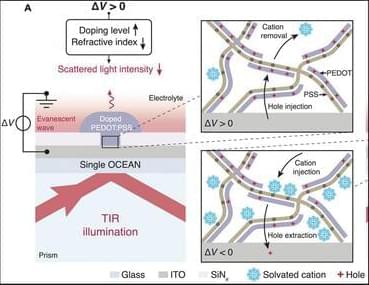

The geometry or shape of a quantum system is mathematically expressed by a tool called the quantum geometric tensor (QGT). It also explains how a quantum system’s state changes when we tweak certain parameters such as magnetic field or temperature.

For the first time, researchers at MIT have successfully measured the QGT of electrons in solid materials. Scientists have been well aware of the methods to calculate the energy and motion of electrons, but understanding their quantum shape was only possible in theory until now.