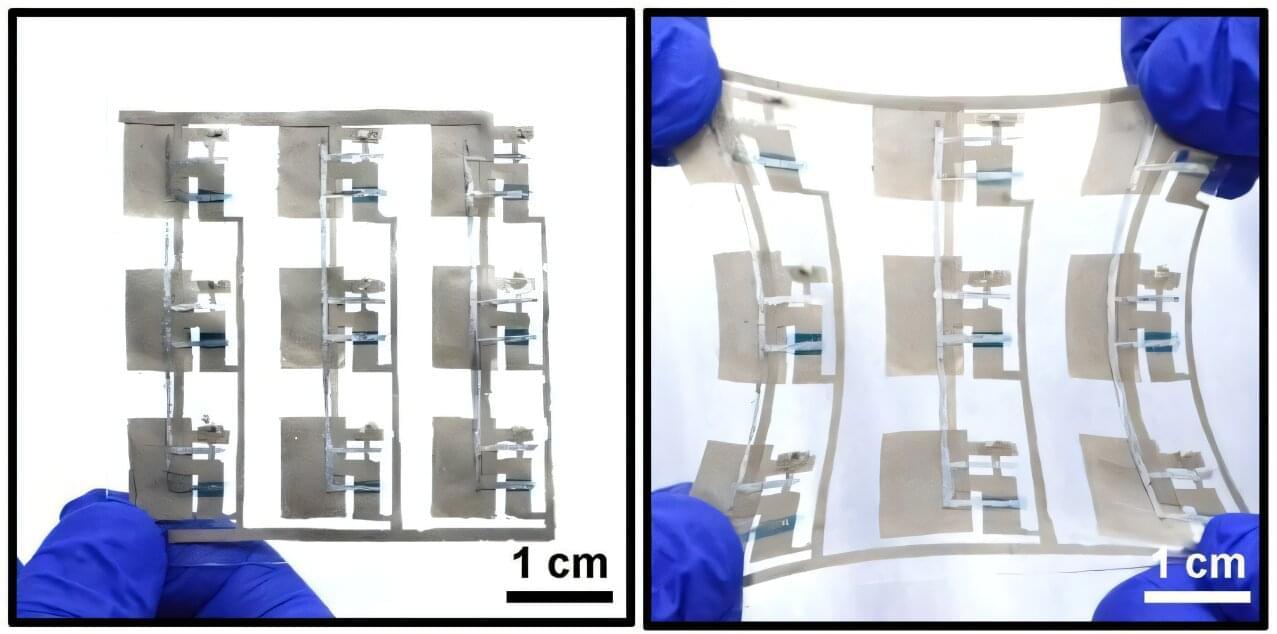

Researcher Cunjiang Yu and his research team, including several of his former students, have announced a significant milestone in materials and electronics engineering: the creation of what they call “rubbery CMOS,” which provides the same functionality as conventional CMOS (complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor) circuits, but is made from entirely different materials.

The research is published in the journal Science Advances.

The great benefit of rubbery CMOS is that it provides the circuit functionality of conventional CMOS while also being stretchable and deformable.