In a quiet control room in northern Chile, a dozen people held their breath at the same time.

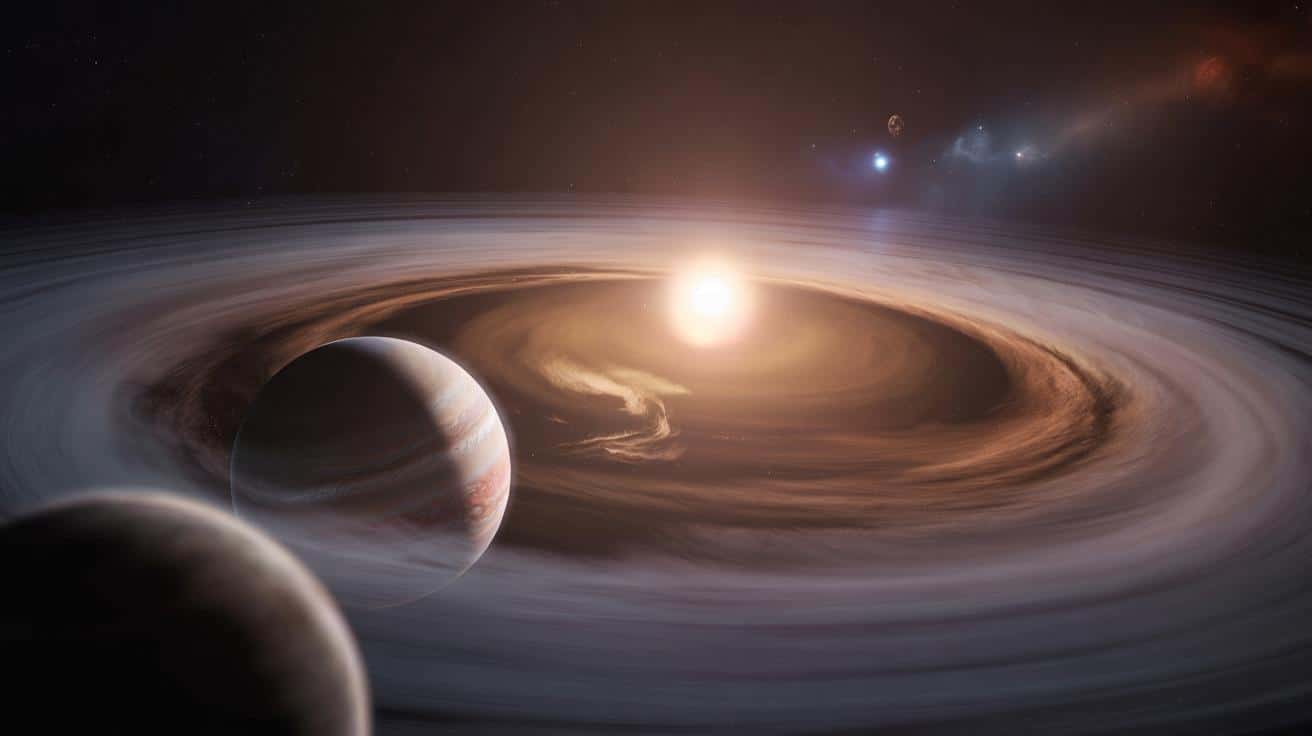

The monitors glowed a cold blue, showing a disc of dust and gas 625 light-years away, circling a young star known as PDS 70. At first glance, it looked like so many other protoplanetary disks astronomers have seen before. But then the data sharpened, the patterns cleared, and something jumped out that nobody had *ever* seen so clearly: a place where moons are being born in real time.

The room didn’t erupt in shouts. It was slower than that. A whispered “no way”, a chair rolling back, someone rubbing their forehead like they’d been staring at the sun too long. On the screen, the “moon factory” came into focus: a ring of material around a newborn planet, turning raw space dust into future worlds. Everyone present knew they were staring at a first in human history.