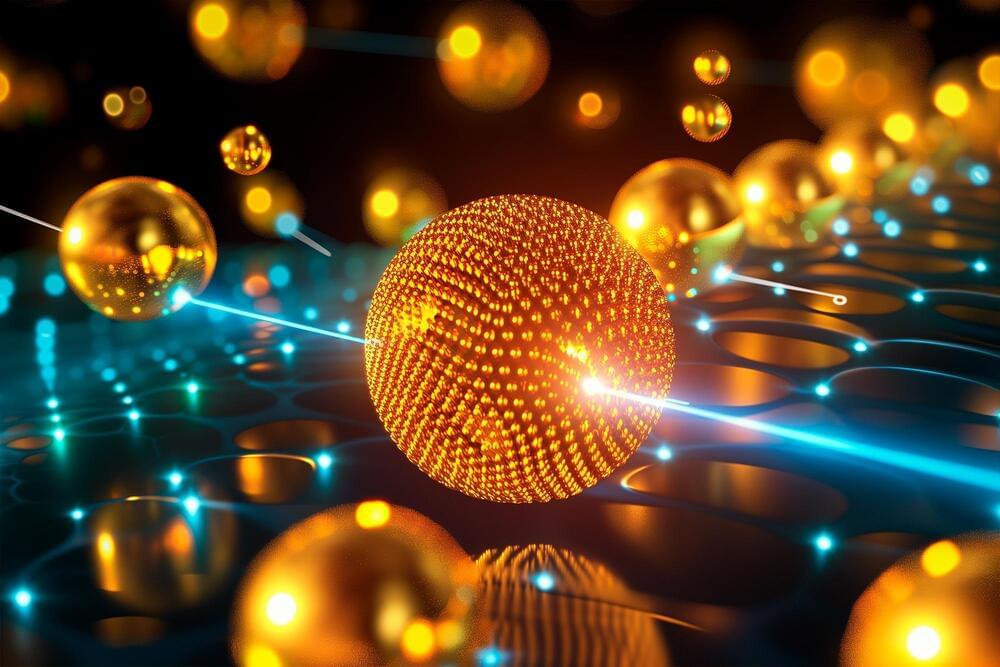

A new protective layer developed by researchers improves gold catalysts’ durability, potentially expanding their industrial applications and efficiency. Credit: SciTechDaily.com.

A protective layer applied to gold nanoparticles can boost its resilience.

For the first time, researchers including those at the University of Tokyo discovered a way to improve the durability of gold catalysts by creating a protective layer of metal oxide clusters. The enhanced gold catalysts can withstand a greater range of physical environments compared to unprotected equivalent materials.