Aubrey de Grey, Chairman and Chief Science Officer of the Methuselah Foundation, presents a realistic scenario for 2020 in which everyone knows we will defeat the aging process.

Category: life extension – Page 405

Dr. Brian Kennedy — Preventive Medicine in an Aging Society

At our first online conference, Ending Age-Related Diseases 2020, Dr. Brian Kennedy of the National University of Singapore discussed the aging population of Singapore, the need for comprehensive healthcare, alpha-ketoglutarate and its effects against frailty in mice, ongoing trials of ketoglutarate in humans, spermidine against obesity, the role of biomarkers, and the importance of keeping people well rather than simply treating them when they are sick.

Ageing Can Be A Thing Of The Past

#aubreydegrey #ageing #ucaststudios #thetalkspot

The Talk Spot is an interview show where we have guests from all backgrounds on. This episode features returning guest Aubrey de Grey.

LAST EPISODE: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXe5YPt_tbA&list=PL1-9Dd…-u&index=2

———————————————————-

Today’s episode is brought to you by The Tax Defense Group and Writer Junkie.

Call The Tax Defense Group today at (800) 850‑7973 and you can visit them online at www.TheTaxDefenseGroup.com.

Call Writer Junkie today at (805) 587‑7966 and you can visit them online at www.WriterJunkie.com.

New Map Charts Genetic Expression Across Tissue Types, Sexes

From the data, the GTEx team could identify the relationship between specific genes and a type of regulatory DNA called expression quantitative trait loci, or eQTL. At least one eQTL regulates almost every human gene, and each eQTL can regulate more than one gene, influencing expression, GTEx member and human geneticist Kristin Ardlie of the Broad Institute tells Science.

Another major takeaway from the analyses was that sex affected gene expression in almost all of the tissue types, from heart to lung to brain cells. “The vast majority of biology is shared by males and females,” yet the gene expression differences are vast and might explain differences in disease progression, GTEx study coauthor Barbara Stranger of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine tells Science. “In the future, this knowledge may contribute to personalized medicine, where we consider biological sex as one of the relevant components of an individual’s characteristics,” she says in a statement issued by the Centre for Genome Regulation in Barcelona, where some of the researchers who participated in the GTEx project work.

Another of the studies bolsters the association between telomere length, ancestry, and aging. Telomere length is typically measured in blood cells; GTEx researchers examined it in 23 different tissue types and found blood is indeed a good proxy for overall length in other tissues. The team also showed that, as previously reported, shorter telomeres were associated with aging and longer ones were found in people of African ancestry. But not all earlier results held; the authors didn’t see a pattern of longer telomeres in females or constantly shorter telomeres across the tissues of smokers as previous studies had.

Not everyone is singing the project’s praises. Dan Graur, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Houston who often criticizes big projects like GTEx, tells Science the results are hard to parse and there was little diversity, with 85 percent of the tissue donors being white. He also was critical of the use of deceased donor tissue, questioning if it truly reflects gene activity in living humans. “It’s like studying the mating behaviour of roadkill.”

Other scientists say there’s much work to be done. The gene regulation map leaves many unanswered questions about the exact sequences that cause disease and how gene regulation systems work in tandem. Genomicist Ewan Birney, the deputy director general of EMBL, tells Science, “We shouldn’t pack up our bags and say gene expression is solved.”

A decade-long effort to probe gene regulation reveals differences between males and females, points to essential regulatory elements, and offers insight into past work on telomeres.

Linking calorie restriction, body temperature and healthspan

Cutting calories significantly may not be an easy task for most, but it’s tied to a host of health benefits ranging from longer lifespan to a much lower chance of developing cancer, heart disease, diabetes and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s.

A new study from teams led by Scripps Research Professors Bruno Conti, Ph.D., and Gary Siuzdak, Ph.D., illuminates the critical role that body temperature plays in realizing these diet-induced health benefits. Through their findings, the scientists pave the way toward creating a medicinal compound that imitates the valuable effects of reduced body temperature.

The research appears in Science Signaling.

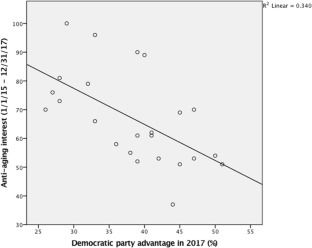

The Relationship between Political Ideology and the Pursuit of Staying Forever Young

US conservatives have a stronger desire to stay forever young than liberals according to this study.

In an era defined by an aging population, the desire to look younger is so great, that the anti-aging industry is expected to grow by hundreds of billions of dollars within only a few years’ time. This research aims to investigate how the increasing interest to look younger is related to political ideology. We propose that accepting the ideal beauty of youthful bodies and pursuing physical youthfulness would be more prevalent among conservatives. We build this upon previous research showing that political conservatism is related to the acceptance of norms and values, as well as having strict boundaries for social perceptions and sensitivity to threat and losses. We conducted a pilot study which revealed that the queries related to anti-aging were more popular in states where political conservatism was higher in the US. Moreover, a survey among American participants revealed that conservatives tended to show a greater interest in preserving their youthfulness, and that they had more resistant attitudes toward aging. Moreover, they exhibited higher preferences for anti-aging benefits, compared to liberals and moderates. These findings contribute to extant literature on political psychology, body ideal, and ageism by demonstrating the relationship between political ideology and the pursuit of youthfulness, which is a neglected but critical dimension of the beauty ideal.

Re-activating Youth Boosting Genes to Reverse Human Aging By 2030

As you get older, key genes that maintain life are no longer activated. George Church is focused on turning youth-boosting genes back on.

His company, Rejuvenate Bio, has begun clinical trials in old dogs. This will help us determine which ages of humans would best benefit. George believes they will be able to help people who are already quite old and show signs of decline. They are looking at extending absolute lifespan. Extending human lifespan will take years to get reliable results.

They have published results on three genes. Those genes already helped reverse osteoarthritis, high-fat obesity and diabetes, heart damage, and kidney disease. They will soon add cancer and neurodegenerative diseases to the list of reversible conditions.

Scientists May Have Discovered a Way to to Slow Aging

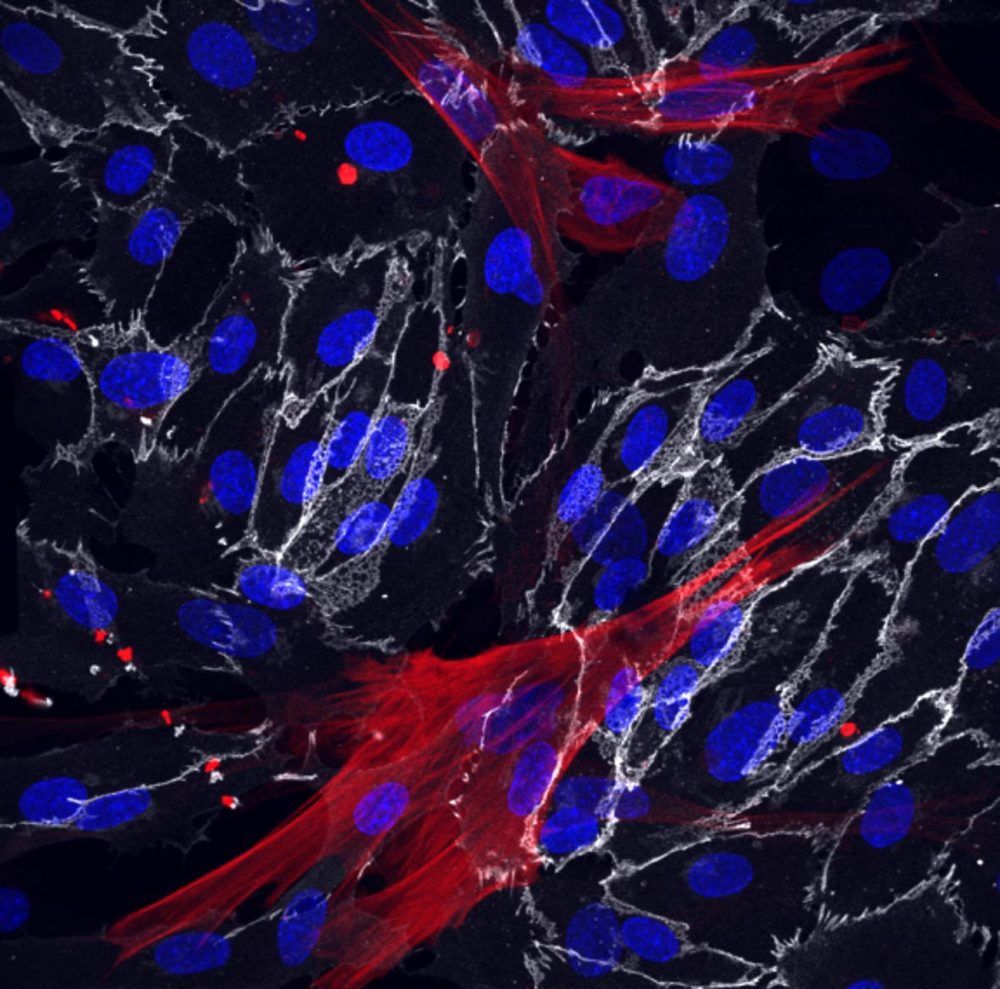

Salk study is the first to reveal ways cells from the human circulatory system change with age and age-related diseases.

Salk scientists have used skin cells called fibroblasts from young and old patients to successfully create blood vessels cells that retain their molecular markers of age. The team’s approach, described in the journal eLife on September 8, 2020, revealed clues as to why blood vessels tend to become leaky and hardened with aging, and lets researchers identify new molecular targets to potentially slow aging in vascular cells.

“The vasculature is extremely important for aging but its impact has been underestimated because it has been difficult to study how these cells age,” says Martin Hetzer, the paper’s senior author and Salk’s vice president and chief science officer.

How Far We Can Wind Back The Clock Ft. David Sinclair | Think Inc.

This is a part of a longer interview which you can watch in parts or listen in one go though it is posted on youtube as audio only for the latter.

Let’s say we find a way to reverse aging. How far could we wind things back and when should we do it?

David Sinclair and Adam Spencer tackling the thorny questions around aging, including how far could we turn back the biological clock, how would we do it, and when in our lifetime should we hit the reset button.

This clip is a recording from our Outside The Box series — an event where David examined how our understanding of aging as a disease is developing, and describes some of the simple methods anyone can use to live a healthier life for longer.

The event was hosted by Australian science communicator and radio personality, Adam Spencer.

Insights into the structure and function of Est3 from the Hansenula polymorpha telomerase

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme, which maintains genome integrity in eukaryotes and ensures continuous cellular proliferation. Telomerase holoenzyme from the thermotolerant yeast Hansenula polymorpha, in addition to the catalytic subunit (TERT) and telomerase RNA (TER), contains accessory proteins Est1 and Est3, which are essential for in vivo telomerase function. Here we report the high-resolution structure of Est3 from Hansenula polymorpha (HpEst3) in solution, as well as the characterization of its functional relationships with other components of telomerase. The overall structure of HpEst3 is similar to that of Est3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human TPP1. We have shown that telomerase activity in H. polymorpha relies on both Est3 and Est1 proteins in a functionally symmetrical manner. The absence of either Est3 or Est1 prevents formation of a stable ribonucleoprotein complex, weakens binding of a second protein to TER, and decreases the amount of cellular TERT, presumably due to the destabilization of telomerase RNP. NMR probing has shown no direct in vitro interactions of free Est3 either with the N-terminal domain of TERT or with DNA or RNA fragments mimicking the probable telomerase environment. Our findings corroborate the idea that telomerase possesses the evolutionarily variable functionality within the conservative structural context.