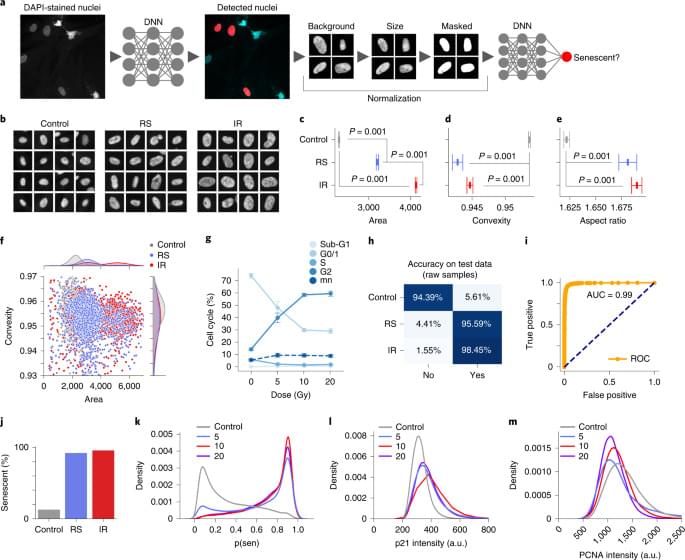

To evaluate the accuracy of the models28, we sampled from the BNN or deep ensemble to determine their uncertainty predictions (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b). Correct predictions are oriented toward the lower and higher range of the output, representing greater certainty about samples’ states, whereas incorrect predictions tend towards the 0.5 threshold. We can therefore assume higher confidence in a model’s predictions by removing the predictions in the middle using thresholds. We evaluated a range of thresholds with several models (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f), which show a substantial increase in accuracy due to the ambiguous samples being discarded, including the ensemble of normalized models reaching accuracy of 97.2%. A similar approach was applied to other models, including the IR and RS models (Extended Data Fig. 3g, h), raising accuracy by 10–15%, although this reduces the number of cells considered.

To better understand the development of the senescent phenotype and how nuclear morphology changes over time, we analyzed human fibroblasts induced to senescence by 10 Gy IR and imaged at days 10, 17, 24 and 31. The predictor identifies senescence at all four times points with probability that increases from days 10 to 17 but declines by day 31 (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Interestingly, examining the probability distribution of the predictor it was apparent that a growing peak of nonsenescent cells appear after day 17, suggesting that a small number of cells were able to escape senescence induction and eventually overgrow the senescent cells (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Indeed, when investigating markers of proliferation, we see that over the time course, PCNA declines until day 17, after which the expression starts to return (Extended Data Fig. 4c). p21Cip1 follows an inverse pattern with stain intensity increasing initially and then declining slightly by day 31 (Extended Data Fig. 4D). We also saw a decrease in DAPI intensity for days 10 and 17, indicating senescence, but a reversion to control level by day 31 (Extended Data Fig. 4e). To confirm that the predictor accurately determined senescence even 31 days after IR, we evaluated if markers of proliferation and senescence correlated with predicted senescence. Accordingly, cells with predicted senescence had higher p21Cip1 levels, lower PCNA and lower DAPI intensities and vice versa (Extended Data Fig. 4f–h). Morphologically, area and aspect are higher for predicted senescence, whereas convexity is lower (Extended Data Fig. 4i–k). Finally, a simple nuclei count confirms growth, following IR treatment (Extended Data Fig. 4l). Overall, the senescence predictor captures the state during development in agreement with multiple markers and morphological signs.

Senescent cells are associated with the appearance of persistent nuclear foci of the DNA damage markers γH2AX and 53BP1 (refs. 31,32). Our base data set including control, RS and IR lines were examined for damage foci using high-content microscopy, where we found the mean count for controls to be below 1 for each marker, whereas RS had 4.0 γH2AX and 2.0 53BP1 foci and IR had 3.4 γH2AX and 3.0 53BP1 foci (Fig. 4a, b and Extended Data Fig. 5a). We calculated the Pearson correlation between predicted senescence and γH2AX and 53BP1 foci counts and found that across all conditions, there is a moderately strong correlation of around 0.5 (Fig. 4c). This association is also visible when simply plotting foci counts and senescence prediction, which shows predicted senescence flipping from low to high, along with shifts in foci counts (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Our feature reduction masked internal nuclear structure, but it is nonetheless notable that senescence prediction correlates with foci count. We also compared the correlation between predicted senescence and area, where we see a correlation of around 0.5. In sum, there is a considerable correlation between foci counts and senescence.