My new policy article for the HuffPost on why more than ever we need to avoid war and armed conflict:

Some of the early years of my adult life were in conflict zones as a journalist—which included covering the Pakistan/Indian Kashmir conflict for the National Geographic Channel and The New York Times Syndicate. War zones are terrifying. One always is worried about bullying soldiers, speeding armed military vehicles, stray bullets, and whether there’s a roadside bomb on your path. Anyone that approaches you is suspect and could be carrying ready-to-detonate explosives.

One thing conflict zones teach you is that freedom is precious. The nearly 70-year Kashmir conflict has approximately a half million soldiers involved, so even if they’re supposedly on your side (depending on what country you’re in), you still feel under siege. My time in certain parts of Sudan, Israel, Palestine, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, Mali, and Yemen left me with the same feeling.

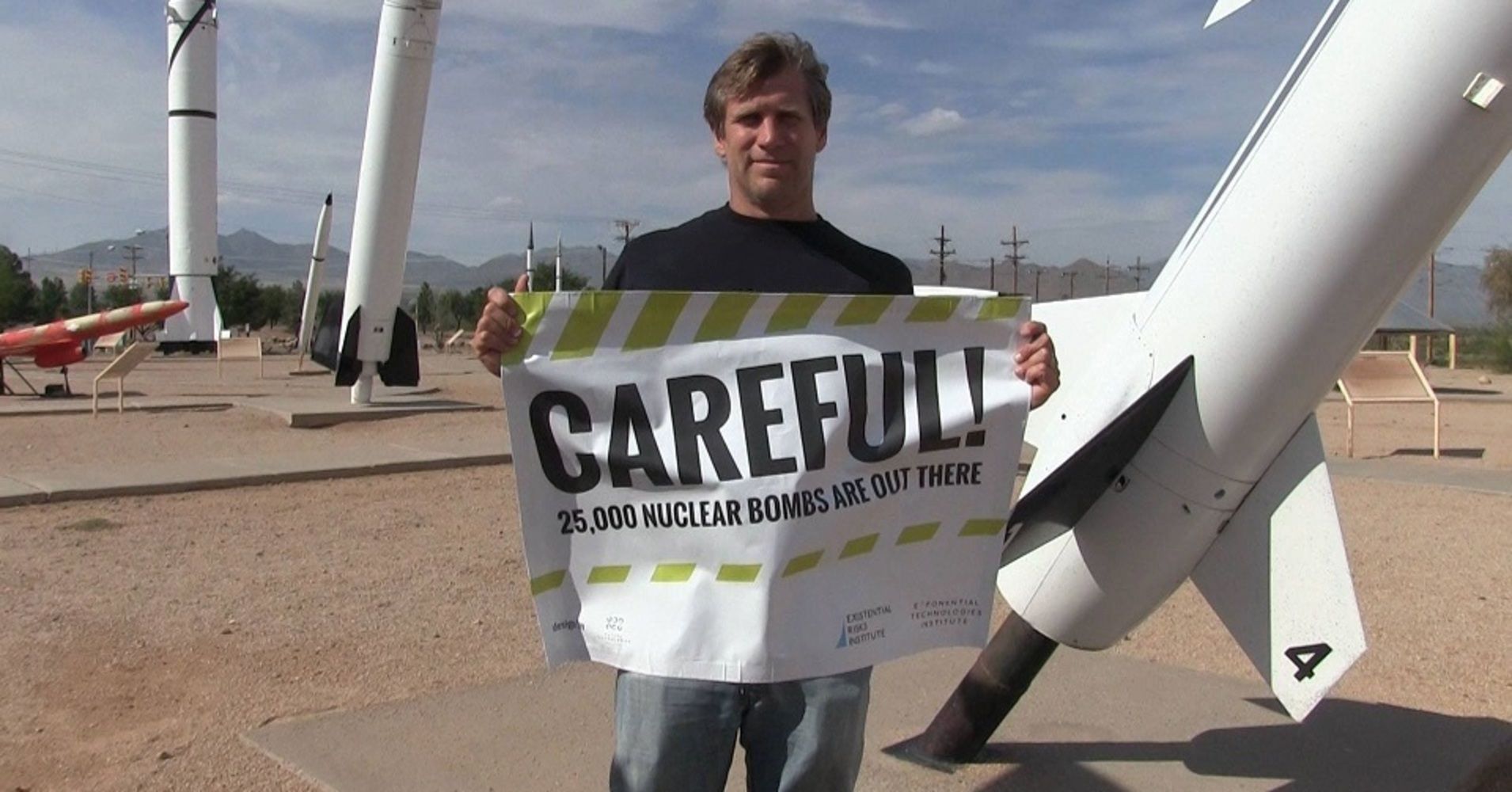

We face an unusual time with President Trump, whose bold behavior could prove dangerous to stable foreign policy. This situation has now become even more worrisome this month when Russia’s Vladimir Putin, according to RT, said publicly that whoever “leads in artificial intelligence will rule the world.” Some experts believe we will have an AI equivalent to human intelligence in less than 10 years time—which means in 15–20 years time, AI will far outdo human thinking and could be in control of all nuclear weaponry on the planet.

For this reason, nothing is more critical for nations and peoples to strive for peaceful times and to get along with one another. In any kind of modern conflict or 21st Century arms race—AI, genetic engineering, or nuclear arms—we likely will lose some of our freedoms and sense of security.