Here, in this article, I will try to give you an idea of how a genetic algorithm works and we will implement the genetic algorithm for function optimization. So, let’s start.

Salamanders and lizards can regrow limbs. Certain worms and other creatures can generate just about any lost part — including a head — and the latest genetics research on body part regeneration is encouraging.

Since they are adult stem cells that have reverted back to a less developed — more pluripotent — state, iPSCs remind scientists of the stem cells that enable lizards to regrow limbs, and zebrafish to regrow hearts. When it comes to limbs, the understanding the regrowth process could help scientists promote nerve regeneration in cases when a limb is severely damaged, but not physically lost. Nerves of the human peripheral nervous system do have the ability to regrow, but whether this actually happens depends on the extent of the injury, so understanding the stem cell physiology in zebrafish and other animals could help clinicians fill the gap. The knowledge gained also could impact development of treatments aimed at promoting nerve regrowth in the central nervous system, for instance in the spinal cord after an injury.

Caveats

Even where regeneration is natural for humans, numerous regeneration cycles can put a person at greater risk of cancer. In the liver, for instance, disease can result in liver cancer largely because the organ produces new cells to replace the damaged ones. This is what happens in cirrhosis and after certain viral conditions when there are periods when regeneration overtakes liver deterioration. Prometheus avoided this fate, but we don’t know how well the process would work in humans, if a regenerative system based on iPSCs or some other types of stem cell is used clinically on a large scale. Regenerative medicine is promising and exciting to hear about. But we are at a very early stage, and reports on limb regrowth should be taken with caution.

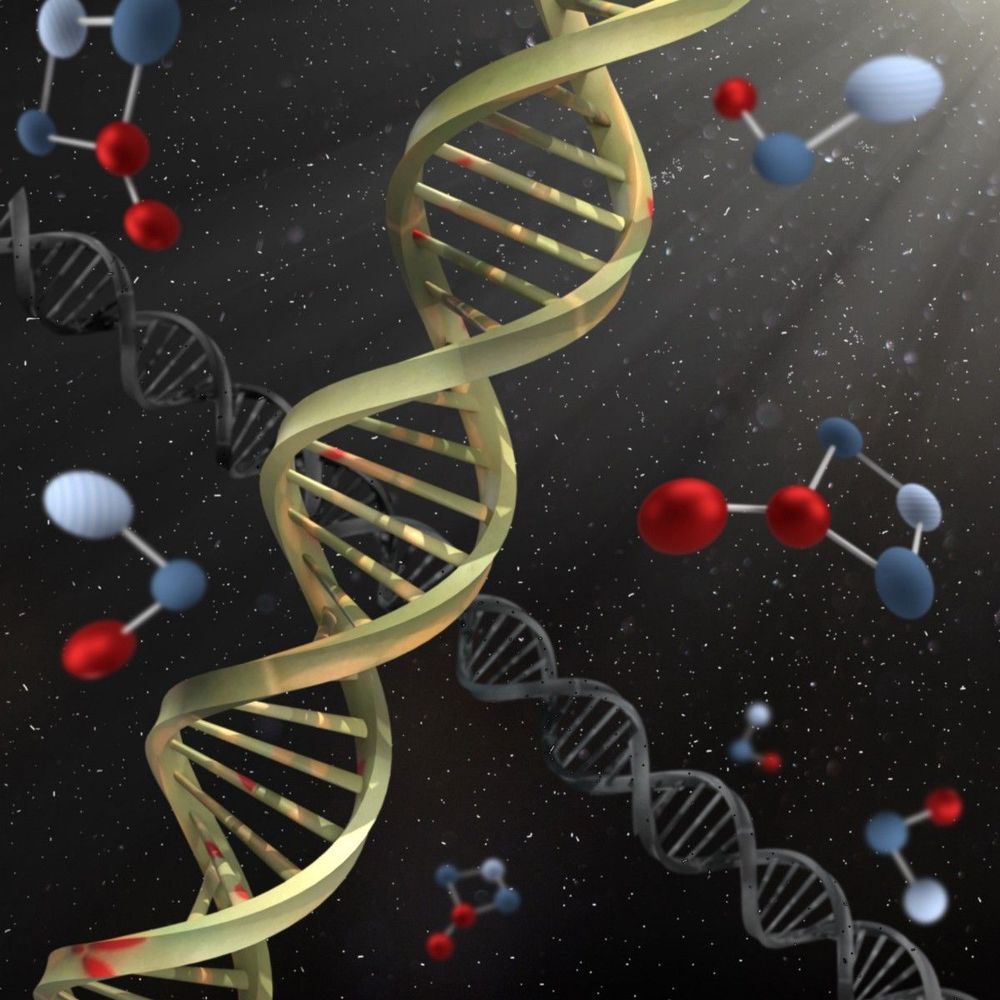

Drexel University researchers have reported a method to quickly identify and label mutated versions of the virus that causes COVID-19. Their preliminary analysis, using information from a global database of genetic information gleaned from coronavirus testing, suggests that there are at least six to 10 slightly different versions of the virus infecting people in America, some of which are either the same as, or have subsequently evolved from, strains directly from Asia, while others are the same as those found in Europe.

First developed as a way of parsing genetic samples to get a snapshot of the mix of bacteria, the genetic analysis tool teases out patterns from volumes of genetic information and can identify whether a virus has genetically changed. They can then use the pattern to categorize viruses with small genetic differences using tags called Informative Subtype Markers (ISM).

Applying the same method to process viral genetic data can quickly detect and categorize slight genetic variations in the SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the group reported in a paper recently posted on the preliminary research archive, bioRxiv. The genetic analysis tool that generates these labels is publicly available for COVID-19 researchers on GitHub.

Just like a virus hijacks your cells and forces them to churn out more copies of the virus, this vaccine is expected to automate the production of those particles, which B-cells and T-cells — the biological hunter-seekers of the immune system — can use to ready themselves to fight the real-deal coronavirus.

The main difference between this sort of DNA-based vaccine and a traditional one, Slavcev told Futurism, is that it relies on the person’s cells to create the mock virus instead of merely exposing them to an inert version of the real virus.

“Personal genetics only has to do with how the vaccine is presented,” Slavcev told Futurism, regarding the decision to develop a DNA-based vaccine. “There is some variation between individuals and populations, but in this case the DNA is just to improve immune response and make it mimic a viral infection as closely as possible to stimulate the most effective immune response.”

Via Harvard David A. Sinclair “The coronavirus is part bat & part human virus. A new study says the Frankenstein event happened well before its transmission to humans. Wait, what? Humans first infected bats?

The intermediate Frankenstein coronavirus has part human/part bat versions of the spike protein (the knobs on the outside of the virus & what COVID-19 vaccines target). Coronafrankenstein is formally called RaTG13, the name, rank & serial # of a horseshoe bat sample. If we gave bats coronavirus first, then people, including scientists, should stay away from bats especially if they don’t feel well. That’s why, as much as I like cats, I don’t like how they can catch it from us. It’s a potentially vicious cycle.

The new study says a mutation has changed the spike protein of an Indian strain of coronavirus that likely reduces its ability to transmit, but “raises the alarm that the ongoing vaccine development may become futile in future epidemics” like seasonal flu.”

Monitoring the mutation dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 is critical for the development of effective approaches to contain the pathogen. By analyzing 106 SARS-CoV-2 and 39 SARS genome sequences, we provided direct genetic evidence that SARS-CoV-2 has a much lower mutation rate than SARS. Minimum Evolution phylogeny analysis revealed the putative original status of SARS-CoV-2 and the early-stage spread history. The discrepant phylogenies for the spike protein and its receptor binding domain proved a previously reported structural rearrangement prior to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Despite that we found the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 is particularly more conserved, we identified a mutation that leads to weaker receptor binding capability, which concerns a SARS-CoV-2 sample collected on 27th January 2020 from India. This represents the first report of a significant SARS-CoV-2 mutant, and raises the alarm that the ongoing vaccine development may become futile in future epidemic if more mutations were identified.

Humans and all other living things have DNA, which contains hereditary information. The information in your DNA gives your cells instructions for producing proteins. Proteins drive important body functions, like digesting food, building cells, and moving your muscles.

Your DNA is the most unique and identifying factor about you—it helps determine what color your eyes are, how tall you are, and how likely you are to have certain health problems. Even so, over 99% of DNA sequences are the same among all people. It is the remaining 1% that explains much of what makes you, you!

DNA is arranged like two intertwined ropes, in a structure called a double helix (see figure 1). Each strand of DNA is made of four types of molecules, also called bases, attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone. The four bases are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine ©, and thymine (T). The bases pair in a specific way across the two strands of the helix: adenine pairs with thymine, and cytosine pairs with guanine.

UC San Francisco researchers have discovered how a mutation in a gene regulator called the TERT promoter—the third most common mutation among all human cancers and the most common mutation in the deadly brain cancer glioblastoma—confers “immortality” on tumor cells, enabling the unchecked cell division that powers their aggressive growth.

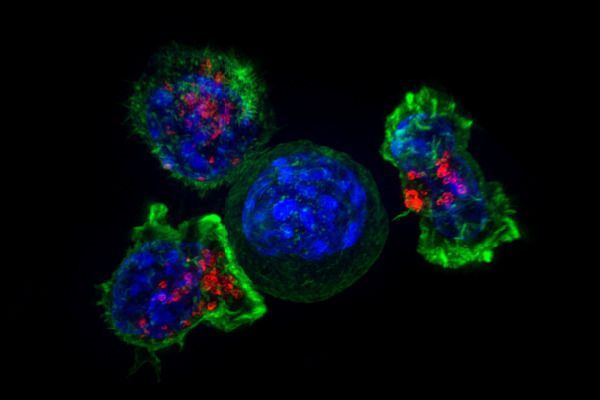

The research, published September 10, 2018 in Cancer Cell, found that patient-derived glioblastoma cells with TERT promoter mutations depend on a particular form of a protein called GABP for their survival. GABP is critical to the workings of most cells, but the researchers discovered that the specific component of this protein that activates mutated TERT promoters, a subunit called GABP-ß1L, appears to be dispensable in normal cells: Eliminating this subunit using CRISPR-based gene editing dramatically slowed the growth of the human cancer cells in lab dishes and when they were transplanted into mice, but removing GABP-ß1L from healthy cells had no discernable effect.

“These findings suggest that the ß1L subunit is a promising new drug target for aggressive glioblastoma and potentially the many other cancers with TERT promoter mutations,” said study senior author Joseph Costello, Ph.D., a leading UCSF neuro-oncology researcher.