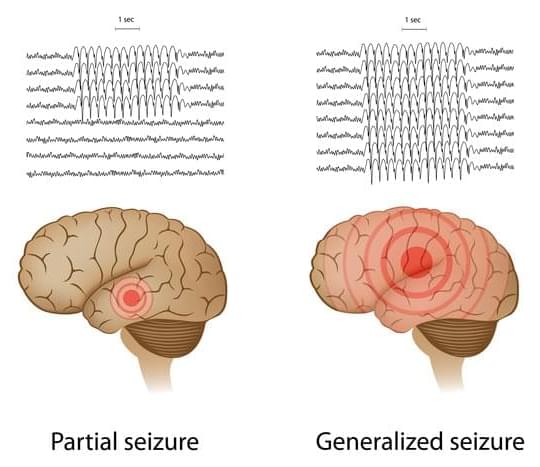

To date, scientists have largely been in the dark with regard to how individual circuits operate in the highly branched networks of the brain. Mapping these networks is a complicated process, requiring precise measurement methods. For the first time, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen, Germany, together with researchers from the Ernst Strüngmann Institute in Frankfurt and Newcastle University in England, have now functionally proven a so far poorly understood neural connection in the visual system of monkeys using optogenetic methods. To this end, individual neurons were genetically modified so that they became sensitive to a light stimulus.

For decades microstimulation was the method of choice for activating neurons – the method proved to be reliable and accurate. That is why it is also used medically for deep brain stimulation. The Tübingen-based scientists were now able to show that optogenetics, a biological technique still in its infancy, delivers comparable results.

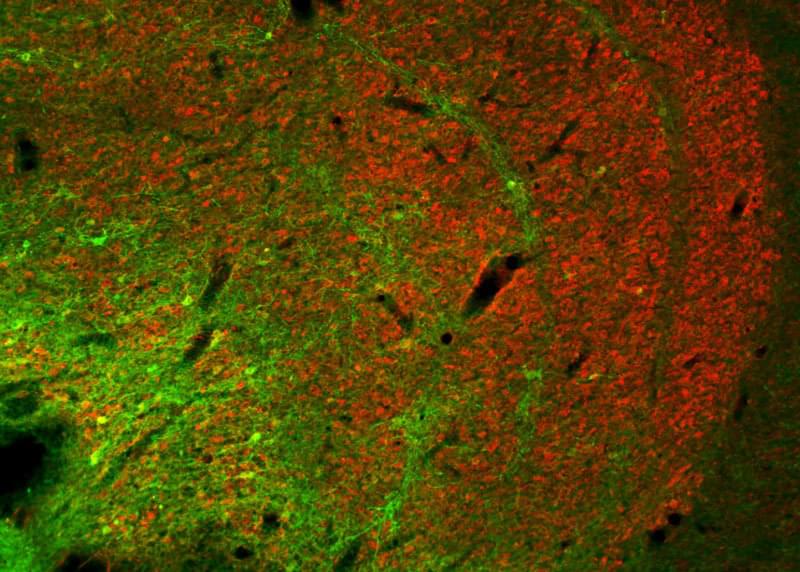

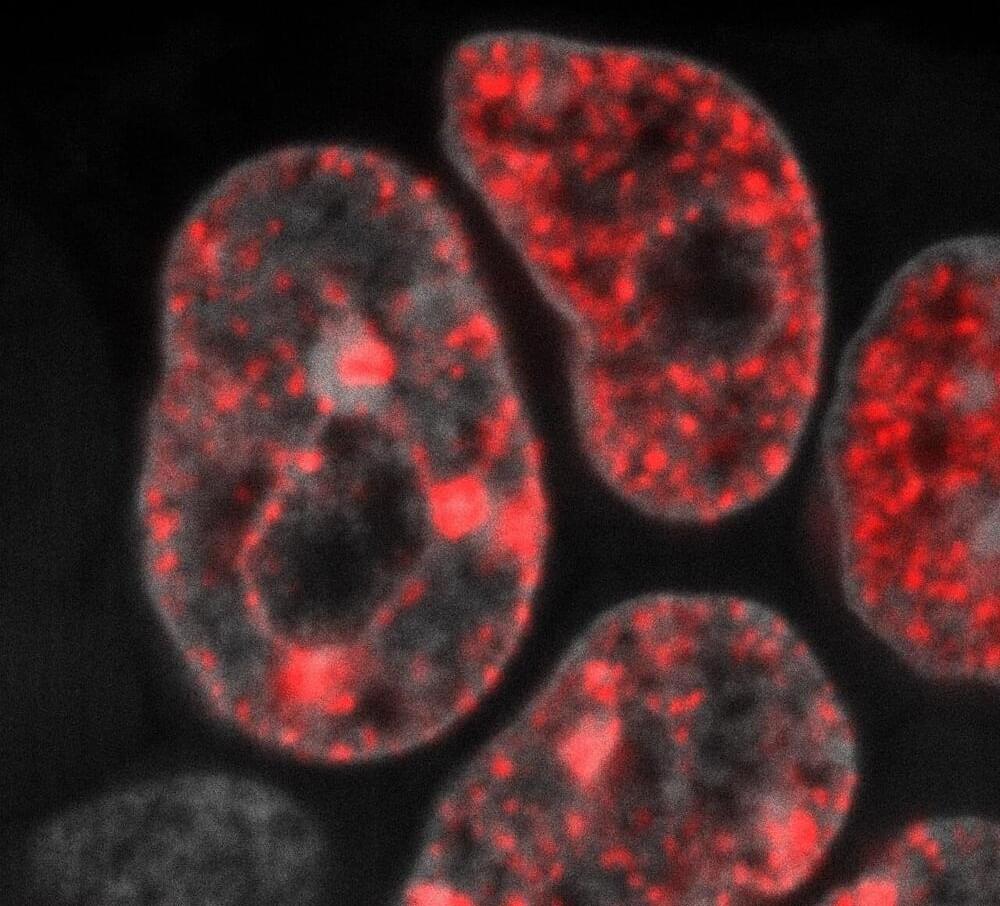

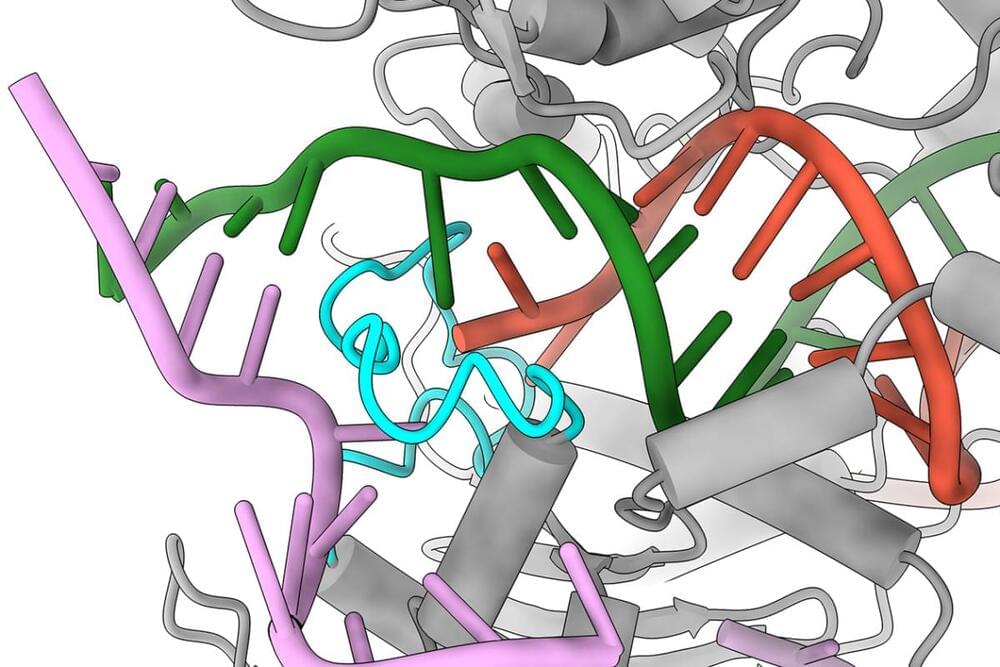

With optogenetics it is possible to directly influence the activity of neurons by light. To do this individual neurons are genetically modified with the help of viruses to express light-sensitive ion channels in their cell membrane. Through blue light pulses delivered directly into the brain, the modified neurons can then be systematically activated.